And so my review of the year reaches its end in the usual fashion: with the best films I watched for the first time in 2022, plus a few honourable mentions, and a list of notable new releases I missed.

Regular readers may have noticed there’s no “worst” list this year. As I wrote last year, the idea of singling out a list of bad movies has become highly unfashionable in recent years, especially when big-name publications do it. I don’t think such lists are wholly without worth (they acknowledge that, as a film viewer, it’s not all sunshine and roses), and there’s a big difference between a major publication slagging off some recent releases (which may affect those films’ continued financial success and their makers’ careers) and a one-man blog picking a couple of lesser films from what he happened to watch that year (which rarely includes recent releases, and wouldn’t have an impact on them even if it did). Nonetheless, in the spirit of celebrating what you love and staying quiet about the rest, I’ve decided to ditch my “worst” list. (If you want, there’s still the “Least Favourite” award in my monthly Arbies.)

With that said, it’s on with…

The Eleven Best Films I Watched for the First Time in 2022

Continuing with the methodology I’ve used since 2016, this list features the top 10% of my first-time watches from the year. In 2022, the total was 111, which means there are 11 films on this year’s “top 10”.

As ever, it’s not just 2022 releases that are eligible for my 2022 list. Consequently, in recent years I’ve included a ‘yearly rank’ for films that had their UK release during the previous 12 months. However, I watched so few of the year’s big hitters in 2022 that I felt to rank what I did see would be misleading. There are too many acclaimed films omitted only because I’m not able to consider them, not because I don’t think they’re worthy. Hopefully I’ll get back on top of seeing new releases, so a yearly ranking can return in the future.

11

Mona Lisa

Take a noir storyline then run it through gritty “kitchen sink” British sensibilities, and you get this: a film that works as both a neo-noir gangster thriller and a character study of a man revising his views of the world. [Full review.]

10

Prey

Studios keep trying to rehash their ’80s sci-fi/action IPs, and they keep producing mediocre results. Thankfully, someone has finally bucked the trend. Prey works in part because it abandons continuity and takes a back-to-basics approach to its alien menace. Setting it in a completely different time period adds more opportunities for fresh perspectives and developments. It’s such a seemingly simple idea that works so well, and one that’s eminently repeatable. Predators vs knights? Predators vs samurai? Predators vs cowboys? Yes, yes, and yes, please, and anything else you can think of. [Full review.]

Michael Bay has always been a divisive filmmaker. His brash, bombastic style isn’t for everyone. But I think there’s a method to his madness (even when it results in trash) and so, when he’s on form, he remains one of the most exciting action filmmakers. Ambulance shows he’s still got the goods. You could imagine the storyline — after a bank heist goes wrong, two crooks escape in an ambulance, along with the cop they shot and a paramedic trying to save him — being from a 1940s film noir; a grim character study of men under pressure. That side of it is still in there, just dressed up with all the wildness of only-semi-restrained Bayhem. [Full review.]

A thriller about… writing a book? Ah, but when the book in question is the autobiography of a disgraced, potentially criminal former Prime Minister, and the book’s new ghost writer has been brought in because his predecessor died under suspicious circumstances, well, you begin to see where there are questions to be answered. Pierce Brosnan is perfect for the role of a former politician who is 50% charming and 50% believable as a scheming villain, while Ewan McGregor leads us through the twisty plot as an everyman who needs the money but still has a conscience. Will the truth out? [Full review.]

Spielberg, man. If you’d told me a remake of West Side Story would end up in my top ten of the year, I’d have given you a funny look. I didn’t love the original film version, but I also didn’t think it could be bettered — it’s a classic for a reason. Surely any remake was doomed to be lesser? But ah, here comes Steven Spielberg, a director whose style clearly chimes with my taste (in fairness, his work helped define my taste, thanks to watching the likes of Indiana Jones, and Spielberg-produced/-emulating movies such as Back to the Future, at a formative age). His version screams Movie in a way so few films do nowadays, and the changes he and his team have made to the material elevate it even beyond the ’61 film, for my money. [Full review.]

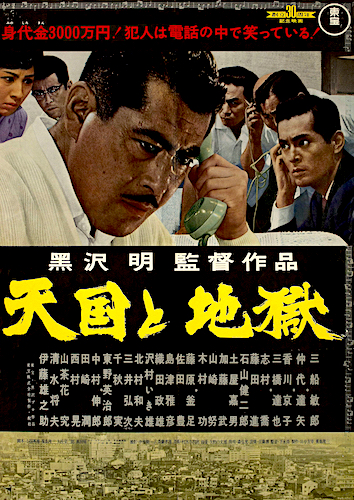

Toshiro Mifune plays a man presented with a life-changing moral dilemma in this thriller from director Akira Kurosawa. It’s a film of two halves: the first, contained almost to one room in near-real-time, sees Mifune’s business executive grapple with a conundrum that could ruin his career; the second becomes intensely procedural as it follows the police investigation and fallout from Mifune’s actions. With its precision attention to detail and healthy dose of mundanity, Kurosawa conjures an intense realism — the film could almost be a documentary; only, a documentary could never be this finely controlled. [Full review.]

5

Mass

Disappointingly relegated to “Sky Original” status here in the UK (usually a dumping ground for low-quality genre movies), Mass is a film that deserves to be more widely seen (the story of too many films buried on random streaming services nowadays, I fear — how many people have actually seen Best Picture winner CODA when it’s locked away on Apple TV+?) The less you know going in the better to be hit with the film’s full emotional weight. And it is a heavy film, but only in a way the befits its subject matter. Made up almost entirely of four people sat round a table talking, it is nonetheless “a blisteringly emotional gut-punch … but, with that, it’s ultimately cathartic.” [Full review.]

4

Encanto

I do enjoy a Disney animation, but one has never broken into my top ten before (Zootropolis was 15th in 2016 and Moana was 16th in 2017). That’s partly the luck of the draw (I watched over 50% more films in each of those years), but also something about how well Encanto works — which, frankly, I can’t quite put my finger on. I mean, all the obvious elements are there: catchy songs, likeable characters, impressively fluid animation, a strong message about what matters. But there’s something else, too; a sprinkling of magic that, for me at least, elevates the film to be something even more special. I say I like a Disney film, but I don’t revisit them too often. I’ve already watched Encanto twice. In one year? That’s not like me! So, hopefully you see my point. [Full review.]

3

Top Gun: Maverick

I feel the need — the need for actors doing their flying stunts for real! Striking usage of the IMAX aspect ratio! Memorable callbacks to the original movie! Cheesy music that fits the tone perfectly! Actual humour! Proper subplots! Top Gun: Maverick is old-fashioned blockbuster moviemaking done with modern sensibilities (can you imagine them actually putting actors in jets back in the ’80s? For one thing, where would they have put those great big film cameras?) Actor/producer Tom Cruise has spent decades now perfecting this brand of big-screen entertainment, and here he shows the next generation how it should be done — both in-film, as a pupil-turned-teacher trying to get a class of the best pilots to be even better, i.e. as good as he is; and in real life too, rocking up in an era when the box office is dominated by previz- and CGI-driven superhero theme-park-rides-as-cinema, and giving us a done-for-real spectacle that kicked all their asses at the box office. The movies, and movie stars, are only dead when Tom Cruise says they are.

2

Les Enfants du Paradis

According to IMDb, when Children of Paradise (to use its translated title) was initially distributed in the USA, it was promoted as “a sort of French-made Gone with the Wind”. It’s not a bad comparison. Not in a literal sense — this isn’t about a spoilt rich girl getting caught up in a civil war on the wrong side — but as an epic, years-spanning romantic melodrama? There are some similarities. It’s the story of a courtesan-turned-actress and the four men in her orbit — a mime artiste, an aspiring actor, a wannabe crook, and a moneyed gent — in and around the theatrical scene of 1830s Paris. It’s told with a style that feels adapted from a novel — it’s got that kind of scope, with its timespan and array of characters, and depth, which feel more like literature than something conceived directly for the screen. In fact, most of the characters are based on real people, which I suppose is neither here nor there, but does add another layer of interest. Whatever makes it work is enough to keep it thoroughly compelling even with a running time over three hours.

1

Manhunter

I first became aware of Manhunter many moons ago, as a piece of footnote trivia in the history of movies: “did you know there was a Hannibal Lector film before Silence of the Lambs?” What a crazy idea! How bad it must have been to be so thoroughly overshadowed by Anthony Hopkins’ Oscar-winning version. Well, the history of the movies is rarely so straightforward; and as the immediate acclaim for Lambs has died down, and its various sequels and prequels have petered away, Manhunter has been able to reemerge somewhat. And so it should, because this is a great movie. Maybe not a great Hannibal Lector movie (Brian Cox is very good in the role, with less of the ticks and tricks that made Hopkins so memorable, but he’s not the focus of the story), but a superb “hunt for a serial killer” thriller. It’s dripping with ’80s style thanks to a director who helped define what that even meant (via his involvement with Miami Vice), while the hero cop, played by William Petersen, feels ahead of his time, struggling with the mental toll of previous cases as he tries to do the right thing and stop another killer. Such a mix of style and substance makes for an all-round fulfilling film; one that I think deserves every bit to be celebrated alongside Jonathan Demme’s more widely-acknowledged movie.

To celebrate it topping my list, Manhunter is on BBC Two tonight at 11:05pm, and on iPlayer for 30 days afterwards.*

As usual, I’d like to highlight a few other films.

Firstly, I wrote this little paragraph not sure where to use it, but here seems a good place. That’s to say: I love a minor film noir. Just a solid, competently made, usually 60-to-80-minute programmer. The highly-regarded Classics are all well and good — I appreciate their quality; why they’re ‘better’ — but, in many respects, I get more actual enjoyment (certainly in a relaxed, easy-viewing sense) from a run-of-the-mill type film. Not bad ones, you understand, just average fare. And here seems a good place to say that because 2022’s Challenge compelled me to watch a few noirs of that ilk. All of them were on the long list for my top ten, but none quite made it. I’m talking about the likes of Christmas Holiday, He Walked by Night, Killer’s Kiss, My Name Is Julia Ross, and Repeat Performance. (I also liked The Killing, but that’s in no way a “minor” noir.) Mr. Soft Touch grew on me as it went on, too, but that’s probably one to only be watched in December.

Next, here’s a recap of the 12 films that won the Arbie for my Favourite Film of the Month. Some have already been mentioned in this post, but some haven’t… In chronological order (with links to the relevant awards), they were Mass, Ghostbusters: Afterlife, West Side Story, High and Low, Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, The Ghost Writer, Ambulance, Repeat Performance, Top Gun: Maverick, The Mission, Manhunter, and Les Enfants du Paradis.

Finally, something I’ve always done in this section is list every film that earned a 5-star rating during the year. In part that’s because there’s normally far too many to include in my list, even if it weren’t for the fact 4-star films usually sneak in too. But this year, there were only six films that received full marks, and all of them made the top 10%, too. Nonetheless, they were Les Enfants du Paradis, High and Low, Manhunter, Mass, Top Gun: Maverick, and West Side Story. Additionally, there were also full marks for my rewatch of the original Scream.

I’ve been creating these “50 Unseen” (as I call them for short) lists for 16 years now, and it doesn’t get any easier to choose what to include — or, rather, what to exclude.

It became a little easier in the past few years, because I was watching so many movies that the number of wide-release titles I’d missed fell, leaving room for more arthouse-y ‘hits’ — films the masses didn’t see but Film People were chatting about. But I watched very few new films this year — just 18 with a 2022 UK release date, down from 30+ in the last few years (with a high of nearly 60 in 2019). Those are small numbers compared to people who watch multiple brand-new films every week, but it had been enough to cover a significant percentage of ‘major’ releases. 18 is… well, not.

With an initial long-list of almost 150 films, I did consider increasing this list to 100 titles. It would be in keeping with the site’s theme, after all. But 100 is such a big number… I mean, history suggests I won’t manage to watch the 50 listed films within the next decade or two, so how long would 100 take? No, 50 simply feels about the ‘right size’ for a list of this type, whereas 100 feels excessive. Besides, something is always going to get left off, it’s just how far down the list that cutoff comes.

So, with the caveat that I’ve inevitably forgotten or misjudged something really noteworthy, here’s an alphabetical list of 50 films designated as being from 2022 that I haven’t yet seen. They were chosen for a variety of reasons, from box office success to critical acclaim via simple notoriety, and hopefully represent a spread of styles and genres, successes and failures.

All Quiet on the Western Front

Avatar: The Way of Water

Babylon

The Banshees of Inisherin

The Batman

Black Adam

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

Blonde

Bullet Train

Crimes of the Future

Decision to Leave

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness

Don’t Worry Darling

Downton Abbey: A New Era

Elvis

Empire of Light

Everything Everywhere All at Once

The Fabelmans

Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore

Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio

Halloween Ends

Jackass Forever

Jurassic World Dominion

Lightyear

Men

The Menu

Minions: The Rise of Gru

Moonfall

Morbius

Nope

The Northman

Pinocchio

Roald Dahl’s Matilda the Musical

RRR

She Said

Smile

Sonic the Hedgehog 2

Strange World

Thor: Love and Thunder

Three Thousand Years of Longing

Turning Red

Tár

The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent

Uncharted

Weird: The Al Yankovic Story

Wendell & Wild

The Whale

X

And that’s another year over.

I gotta say, I’m quite pleased with how quickly I wrapped it all up — I haven’t got my “best” list out by January 6th since 2017. It shouldn’t feel like a rush to get this stuff online, but when many people are sharing their lists before the end of December (or even earlier, in the case of some publications), a week or more into January feels “late”.

Anyway, I’m going to leave a couple of days to let the end of 2022 finally sink in, and then I’ll start waffling on about my targets for 2023.

* Obviously it’s not actually because of my list, just a coincidence. ^

Favourite Film of the Month

Favourite Film of the Month

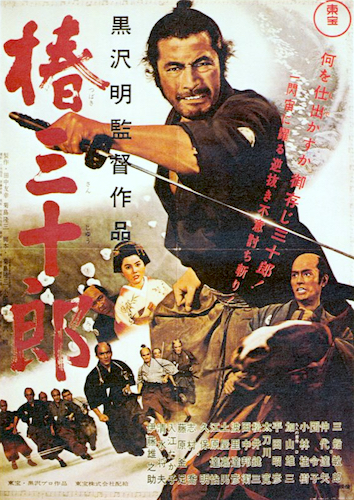

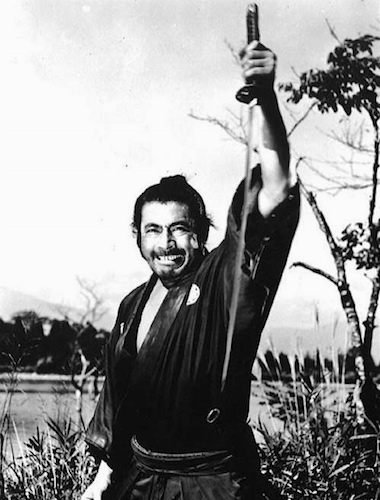

Seven Samurai used to be a striking anomaly amongst the top ten of

Seven Samurai used to be a striking anomaly amongst the top ten of  It’s also unhurried. As Kenneth Turan explains in his essay “The Hours and Times: Kurosawa and the Art of Epic Storytelling” (in the booklet for Criterion’s DVD and Blu-ray releases of the film, and available online

It’s also unhurried. As Kenneth Turan explains in his essay “The Hours and Times: Kurosawa and the Art of Epic Storytelling” (in the booklet for Criterion’s DVD and Blu-ray releases of the film, and available online  The length ensures our investment in the village, too, just as it does for the samurai. They’re not being paid a fortune — in fact, they’re just being paid food and lodging — so why do they care? Well, food and lodging are better than no food and lodging, for starters; and then, having been in the village so long in preparation, they care for it too. It is, at least for the time being, their home. You can tell an audience this, of course, but one of the few ways to make them feel it is to put them there too — and that’s what the length does. To quote from Turan again,

The length ensures our investment in the village, too, just as it does for the samurai. They’re not being paid a fortune — in fact, they’re just being paid food and lodging — so why do they care? Well, food and lodging are better than no food and lodging, for starters; and then, having been in the village so long in preparation, they care for it too. It is, at least for the time being, their home. You can tell an audience this, of course, but one of the few ways to make them feel it is to put them there too — and that’s what the length does. To quote from Turan again, the final scene, the way it’s edited and framed, ties the remaining samurai to their deceased comrades, the living and thriving farmers a distant and separate group. Fighting is the way of the past, perhaps, and peaceful farming the future. Or is the samurai’s only purpose to be found in death, because other than that they are redundant?

the final scene, the way it’s edited and framed, ties the remaining samurai to their deceased comrades, the living and thriving farmers a distant and separate group. Fighting is the way of the past, perhaps, and peaceful farming the future. Or is the samurai’s only purpose to be found in death, because other than that they are redundant? And it wasn’t as if it was overseas viewers who hit on the magic: as Turan reveals, “Toho Studios cut fifty minutes before so much as showing the film to American distributors, fearful that no Westerner would have the stamina for its original length.” The more things change the more they stay the same, I suppose — how many Great Films from Hollywood are ignored by awards bodies and audiences, only to endure in other ways?

And it wasn’t as if it was overseas viewers who hit on the magic: as Turan reveals, “Toho Studios cut fifty minutes before so much as showing the film to American distributors, fearful that no Westerner would have the stamina for its original length.” The more things change the more they stay the same, I suppose — how many Great Films from Hollywood are ignored by awards bodies and audiences, only to endure in other ways? One has to wonder if

One has to wonder if