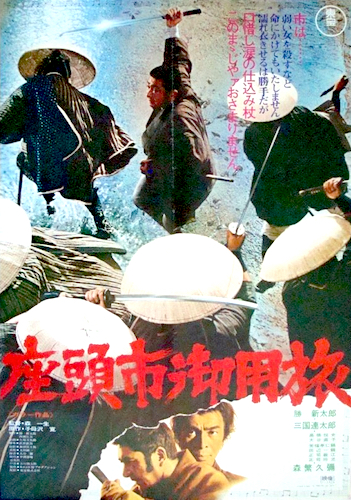

Shintarô Katsu | 93 mins | Blu-ray | 2.35:1 | Japan / Japanese | 15

The 24th and penultimate film in the original Zatoichi series is also the first to be directed by star Shintarô Katsu. (He previously wrote the 21st film, Zatoichi Goes to the Fire Festival, and would later direct 22 episodes of the TV series and write & direct the 1989 revival movie.) Despite such fundamental creative control by the man who arguably knew the character best, Zatoichi in Desperation is widely regarded as one of the series’ worst instalments, and yet you’ll find some people full of praise for it. It’s one of the series’ darkest entries, and I suspect it’s unpopular overall because it’s so grim; but for those who do like it, they love it.

The plot starts with Ichi accidentally causing a polite old woman to fall from a bridge and die — as I said, cheery. The woman was on her way to visit her daughter, Nishikigi (Kiwako Taichi), so Ichi seeks her out. She’s a prostitute, so, as recompense, Ichi sets about raising the funds to free her from prostitution. Meanwhile, 14-year-old Kaede (Kyoko Yoshizawa) is also employed at Nishikigi’s brothel, to earn money to care for her younger brother Shinkichi (Yasuhiro Koume); so when some out-of-town bigwig starts letching over her, well, you can guess what route she’s set to head down. Said bigwig is funding a move by gangsters to crush the local fishermen and set up some kind of modern fishing empire. Just the kind of ordinary folk vs yakuza fight that Ichi would normally find himself embroiled in…

Except he’s busy with Nishikigi, and that doesn’t really change. This is the cornerstone of the film’s moral thesis, which seems to be that the world is a brutal and unjust place. While kind-hearted Ichi is busy helping Nikigiki out of a perhaps-misplaced sense of duty (she doesn’t seem fussed about her mum’s demise, nor with escaping the brothel), he’s missing the people who could really use his help, i.e. Kaede and Shinkichi, or the village’s oppressed fishermen.

And they really could use a hand, because it’s against them that the film’s brutality is fully manifested. The gangsters burn all the villagers’ boats, then murder them for complaining about it; and while Kaede’s busy preparing to have to sell her body at 14, Shinkichi provokes the gangsters and consequently gets brutally beaten to death; and when Kaede finds his body, she commits suicide — and all of that occurs without Ichi even being aware Kaede and Shinkichi exist. Makes you wonder: were events like that playing out just offscreen in every other Ichi movie? Well, not consciously, obviously, but perhaps Katsu is provoking us to wonder about all the people Ichi has failed down the years while he was distracted elsewhere. Maybe our hero is blind in more ways than one.

Aside from the violence, this is also an uncommonly filthy film for the series. First Ichi overhears a whore talking about how taking ten men makes her wet; then he’s hiding in a room while a couple have sex; then later a bunch of yakuza round up a mentally ill kid and start wanking him off until he ejaculates on one of them, for which they give him a beating. Yep, that all happens on screen. (Nearly every review I’ve come across comments on that last scene. Well, no surprise, really — it’s rather striking.)

Hopefully you’re beginning to understand why this movie is so divisive. But if the content wasn’t enough, Katsu seems determined to show off with form, too. His bold directorial style is evident from the off, when the old woman’s fall from the bridge is represented via an impressionistic barrage of flash-cut images. This is followed through the rest of the film by weirdly-framed close-ups and various odd angles. It doesn’t always pay off: the requisite gambling scene is a rehash of a trick from an earlier film, shot with a certain kind of dark tension (Ichi feels in genuine peril from those he swindled) that’s in-keeping with the film’s tone, but the trick itself is less entertainingly performed, the scene not as well paced and constructed. There’s also an atypical score by Kunihiko Murai, which some praise as being ’70s funk, but I thought sounded just like cheesy electronic nastiness. Sometimes his unusual choices emphasise the film’s glum tone, as in the opening credits, which play out in silence over black — not the usual mode for a Zatoichi film, and so it somewhat suggests the goal is to present this as a Serious Movie.

Certainly, many describe this as a more realistic version of Zatoichi than we’ve seen before. It’s removed from the superheroics of the other movies, instead offering a brutal portrait of real violence and how it scars, with innocents suffering unnoticed and even our hero failing to emerge unscathed. Whether that’s realist or just depressive might depend on your view of the world; although, considering the time and place these films are set, I imagine its closer to reality than all of the “Ichi saves everyone” narratives. That either/or extends to the film’s reception: everyone agrees that it’s nastier, darker, and closer to reality than the other Zatoichi films, but whether that’s merited — an interesting diversion — or a case of taking things too far — a low point for the series — is a matter of personal taste.

Personally, then, I appreciate what it was going for, but I wonder if Katsu left it too long to go there. Coming so late in the series means we’re very familiar with the tropes it’s subverting, which is necessary — it works best as a counterpoint to what we’ve already seen rather than as a standalone piece — but it almost feels too late to go about such subversion — it’s a departure from the groove these films have worn for themselves. Maybe Katsu should’ve entrusted such a departure to a more sure-handed director; maybe it’s the roughness of his directorial voice that makes the film what it is.