2013 #102

Nick Hurran | 77 mins | TV (HD) | 16:9 | UK / English | PG

The longest-running science-fiction TV show in the history of the world ever marked its 50th birthday with a feature-length cinema-released one-off special — I think we can count that as a film, right? Good.

The pressure on showrunner/writer Steven Moffat when it came to this special must have been immeasurable. To distill over 30 seasons of television and 50 years of memories into a relatively-short burst of entertainment that would satisfy not only fans, both hardcore and casual, but also Who’s ever-widening mainstream audience. Not only that, but to produce it in 3D, preferably in such a way that the 3D wasn’t pointless, but also that played fine in 2D; and to make it of a scale suitable for a cinema release, but for only a BBC budget; plus, the weight of an unprecedented (indeed, record-shattering) global TV simulcast audience. And all that in the wake of years of griping and disappointment about the direction he’d led the show in, not least the less-than-usual number of episodes being released during the 50th anniversary year as a whole. Yeah, no pressure…

That The Day of the Doctor delivers — and how — is part miracle and part relief, and all joy for the viewer. Well, most viewers — you’ll never please everyone, especially on a show as long-running, diverse, and indeed divisive, as Doctor Who has become. But for the majority it wasn’t just a success, it was a triumph. Evidence? There was that record-breaking global audience; it was the most-watched drama in the UK in 2013; its theatrical release reached #2 at the US box office, despite being on limited screens two days after it aired on TV  (and it made more than double per screen what The Hunger Games 2 took that night); it recently won the audience-voted Radio Times BAFTA for last year’s best TV programme; and, last week, a poll of Doctor Who Magazine readers asserted it was better than the 240 other Who TV stories to crown it the greatest ever made.

(and it made more than double per screen what The Hunger Games 2 took that night); it recently won the audience-voted Radio Times BAFTA for last year’s best TV programme; and, last week, a poll of Doctor Who Magazine readers asserted it was better than the 240 other Who TV stories to crown it the greatest ever made.

Phew.

As we well know, popularity in no way dictates quality, especially when it comes to TV viewing figures or opening-weekend box office takings… but those audience polls tell a different story, don’t they? The story of something that managed to satisfy millions of people who it seemed impossible to please.

There are many individual successes in The Day of the Doctor, which come together to make something that is, at the very least, the sum of its parts. The star of the show, however, is Moffat’s screenplay. Eschewing the “standard” Whoniversary format of bringing back all the past Doctors and a slew of their friends for an almighty stand off with a huge array of popular enemies (so “standard” it was only actually done once), he instead opts to tell a different kind of story: the series is never about the Doctor, just the adventures he has, so what could be more special than shifting that focus? And with the backstory previous showrunner Russell T Davies had created for the revived show in 2005 — the Time War, and the Doctor’s role in ending it — Moffat had the perfect canvas to tap in to our hero.

The Doctor’s role in the Time War has not only dominated many of his actions and personalities since it happened, but it also stands awkwardly with his persona as a whole. Here’s the man who always does the right thing, always avoids violence, always finds another way, even when there is no other way… and this man wiped out all of his people and all of the Daleks? The same man who, in his fourth incarnation, stared at two wires that could erase the Daleks from history and pondered, “do I have the right?”, before concluding that he didn’t? Doesn’t really make sense, does it?

The Doctor’s role in the Time War has not only dominated many of his actions and personalities since it happened, but it also stands awkwardly with his persona as a whole. Here’s the man who always does the right thing, always avoids violence, always finds another way, even when there is no other way… and this man wiped out all of his people and all of the Daleks? The same man who, in his fourth incarnation, stared at two wires that could erase the Daleks from history and pondered, “do I have the right?”, before concluding that he didn’t? Doesn’t really make sense, does it?

So Moffat crafts a story that shows a little of how the Doctor came to make that decision… and then, thanks to this past Doctor getting to see a little of how his future selves reacted to it, the chance to make a different one after all. If that sounds a little bit Christmas Carol-esque, it shouldn’t be a surprise: it’s a favourite form of Moffat’s. Indeed, for a series about time travel, very few pre-2005 Doctor Who stories involve it as a plot point (merely as a mechanism to deliver the main characters into that week’s plot), whereas Moffat has frequently tapped into the whys and hows of that science-fictional ability. In these regards — and others, like the sublime structure where things are established in passing, or for one use, and then resurface unexpectedly later with a wholly different point — The Day of the Doctor is inescapably a Moffat story, albeit one without some of his other, less favourable, predilections that have coloured the series of late.

I think some fans would have preferred a big party history mash-up; they certainly would have liked to see their favourite faces from the past. But let’s be honest: from the classic era, only Paul McGann could pass muster as still being the Doctor he once was (and he got his own, fantastic, mini-episode to prove it); and how the hell do you construct a story with a dozen leading men? It’s clearly enough of a struggle with three. The Doctor is always the cleverest person in the room, so what do you do with multiples of him? Moffat finds ways to make all of the Doctors here (that’d be David Tennant’s 10th, Matt Smith’s 11th, and John Hurt’s newly-created ‘War Doctor’) have something to do, something to say, and something to contribute — because really, the oldest (i.e newest) Doctor should be the most experienced and have all the ideas, right? There are ways round that, but only so many.

I think some fans would have preferred a big party history mash-up; they certainly would have liked to see their favourite faces from the past. But let’s be honest: from the classic era, only Paul McGann could pass muster as still being the Doctor he once was (and he got his own, fantastic, mini-episode to prove it); and how the hell do you construct a story with a dozen leading men? It’s clearly enough of a struggle with three. The Doctor is always the cleverest person in the room, so what do you do with multiples of him? Moffat finds ways to make all of the Doctors here (that’d be David Tennant’s 10th, Matt Smith’s 11th, and John Hurt’s newly-created ‘War Doctor’) have something to do, something to say, and something to contribute — because really, the oldest (i.e newest) Doctor should be the most experienced and have all the ideas, right? There are ways round that, but only so many.

No, instead Moffat treats us to a proper story, rather than an aimless ‘party’… and then serves up a final five or ten minutes that deliver fan-centric treat after treat, without undermining what’s gone before. I guess a lot of that is meaningless to the casual viewer, or is at least unintrusive, but to fans there are moments that provoke cheers and tears — often at the same time. All the Doctors flying in to save the day! Capaldi’s eyes! Tom Baker — as the fourth Doctor, or a future Doctor? Doesn’t matter! And then the final shot, with them all proudly lined up! It’s an array of effective, emotional surprises that far surpasses what could have been achieved if the whole episode had been executed in this style.

Along the way, Moffat nails so many other things. The dialogue and situations sparkle, and frequently gets to have its cake and eat it: familiar catchphrases and behavioural ticks of the 10th and 11th Doctors are trotted out to a fan-pleasing extent, and then Hurt’s aged, grumpier, old-fashioned Doctor gets to criticise their ludicrousness, speaking for a whole generation of fans who hate “timey-wimey” and “allons-y” and all the rest. I think it’s this self-awareness that helps so much with selling the episode to everyone, both calling back to well-known elements of the series that many love, and pillorying their expectedness for those that aren’t so keen. Well, it would be a pretty awful party if you had a cake but couldn’t eat it, right?

Along the way, Moffat nails so many other things. The dialogue and situations sparkle, and frequently gets to have its cake and eat it: familiar catchphrases and behavioural ticks of the 10th and 11th Doctors are trotted out to a fan-pleasing extent, and then Hurt’s aged, grumpier, old-fashioned Doctor gets to criticise their ludicrousness, speaking for a whole generation of fans who hate “timey-wimey” and “allons-y” and all the rest. I think it’s this self-awareness that helps so much with selling the episode to everyone, both calling back to well-known elements of the series that many love, and pillorying their expectedness for those that aren’t so keen. Well, it would be a pretty awful party if you had a cake but couldn’t eat it, right?

Tasked with delivering all this, the cast are uniformly excellent, to the point where it’s difficult to pick a stand out. Hurt makes for a creditable ‘new’ Doctor in a relatively brief amount of screen time, while Tennant slips back into the role as comfortably as he does his suit. Special praise should be reserved for Billie Piper, though, having a whale of a time as the quirky Bad Wolf-inspired interface to The Moment. She could’ve been an excuse for exposition and plot generation, two roles her character does fulfil, but if you think that’s all she was then I suggest you watch again: there’s more complexity at play there; a weapon not only with sentience, but with a conscience too. She’s not Rose Tyler, but perhaps she has a part of her…

Smith and Jenna Coleman are on form too, of course, but as the series’ regular cast members that feels less remarkable. That’s not intended to sell them short, however, as they hold their own against actors who are arguably more, shall we say, established. If there’s one weak link it may be Joanna Page’s eyebrows, possibly the side effect of duelling with an English accent. (Complete aside: I’m rewatching Gavin & Stacey as I write this, and feel horrible even going near criticism of such a lovely person.)

Smith and Jenna Coleman are on form too, of course, but as the series’ regular cast members that feels less remarkable. That’s not intended to sell them short, however, as they hold their own against actors who are arguably more, shall we say, established. If there’s one weak link it may be Joanna Page’s eyebrows, possibly the side effect of duelling with an English accent. (Complete aside: I’m rewatching Gavin & Stacey as I write this, and feel horrible even going near criticism of such a lovely person.)

They’re backed up by a cornucopia of technical excellence. Yes, OK, it’s a TV episode really — but gosh darn, it looks like a movie. I’m sure some would dig in to criticism of the direction (don’t get me started on the increasingly-regular internet commenter’s cry of “the direction was made-for-TV quality”, but suffice to say I generally don’t hold with that as a complaint), but Nick Hurran’s work is suitably slick. The battle of Arcadia is a sequence any modestly-budgeted big screen extravaganza would be proud to contain, and all achieved on a tighter-than-most-people-realise BBC budget. It won a BAFTA Craft award for special effects, which is more than deserved. Combining full-scale effects, CGI, and even model work (personally, I didn’t even realise there were models involved until I read so in an article months later), it looks incredible, with a scale that’s completely appropriate for a major battle in the war to end all wars. Elsewhere there are a few slip-ups, like a bit of heroic slow-mo undermined by not being recorded at a higher frame rate, but these are few and far between.

Credit too to editor Liana Del Giudice, not only for crafting cinematic action sequences, but for stitching together a narrative that is often told with imagery and flashbacks, rather than people stood around chatting. Look at the sequence just after the Doctor sees the painting for the first time as just one clear example. That sequence may be dialogue-driven, but the faded-in and intercut flashbacks and glimpses of other events are what’s really conveying information. This is first-class visual storytelling, not just when compared to the rest of British TV, or international TV, or cinema, but the whole shebang.

Credit too to editor Liana Del Giudice, not only for crafting cinematic action sequences, but for stitching together a narrative that is often told with imagery and flashbacks, rather than people stood around chatting. Look at the sequence just after the Doctor sees the painting for the first time as just one clear example. That sequence may be dialogue-driven, but the faded-in and intercut flashbacks and glimpses of other events are what’s really conveying information. This is first-class visual storytelling, not just when compared to the rest of British TV, or international TV, or cinema, but the whole shebang.

Perhaps (as in “it isn’t, but let’s see what some people think”) the editing is even too snappy. In the run up to the special’s release, some fans moaned about its length: an hour-and-a-quarter wasn’t enough to do justice to 50 years, they said; it should be at least 90 minutes. Which is exactly the kind of ludicrous small-minded pettiness some fanbases talk themselves into these days. Moffat commented in an interview somewhere that his scripts for The Snowmen (the 2012 Doctor Who Christmas special) and A Scandal in Belgravia (the first episode of Sherlock season two) had exactly the same page count, and yet, when shot and edited, one episode was an hour long and the other 90 minutes. Screenwriting is an inexact science like that. I seriously doubt anyone at the BBC commissioned a 75- or 80-minute Doctor Who special; instead, I would imagine Moffat wrote a roughly-feature-length script that seemed achievable within Who’s limited-despite-what-the-Daily-Mail-think budget, then it was filmed, edited, and it ended up being the length it is. Indeed, the scheduler-unfriendly final running time of 77 minutes is merely further indication of such a notion.

Still, you can’t please all of the people all of the time, and not everyone liked The Day of the Doctor: it may’ve topped DWM’s poll, but there were voters who scored it just one out of ten. But then, that’s true of 239 of the series’ 241 stories; and almost 60% of voters gave it a full ten out of ten — that’s a pretty clear consensus. I didn’t get round to voting myself, but I would’ve been amongst them. There are undoubtedly some weak spots that I haven’t flagged up, but conversely, there are myriad other successes — both minor (the opening! The dozens of sly callbacks!) and major (the use of the Zygons! Murray Gold’s music!) — that I haven’t mentioned either.

Still, you can’t please all of the people all of the time, and not everyone liked The Day of the Doctor: it may’ve topped DWM’s poll, but there were voters who scored it just one out of ten. But then, that’s true of 239 of the series’ 241 stories; and almost 60% of voters gave it a full ten out of ten — that’s a pretty clear consensus. I didn’t get round to voting myself, but I would’ve been amongst them. There are undoubtedly some weak spots that I haven’t flagged up, but conversely, there are myriad other successes — both minor (the opening! The dozens of sly callbacks!) and major (the use of the Zygons! Murray Gold’s music!) — that I haven’t mentioned either.

Even if The Day of the Doctor isn’t flawless, as a Doctor Who story — and certainly as a great big anniversary celebration — it is perfect.

Adapted from a short story by Kan Shimozawa, The Tale of Zatoichi was a low-key release for its studio, Daiei: despite being helmed by “a topflight director”*, it was shot in black and white, its leading man, Shintarô Katsu, “was not really a huge star”, and his co-star, Shigeru Amachi, “had been one of the main stars at Shintoto studios before it went bankrupt and ceased production” — surely a mixed blessing. And yet it was “a surprise hit… touch[ing] a nerve with Japanese audiences, who loved to root for the underdog.” Despite the fact our hero gives up his sword at the end of the film, Daiei produced a sequel, and… well…

Adapted from a short story by Kan Shimozawa, The Tale of Zatoichi was a low-key release for its studio, Daiei: despite being helmed by “a topflight director”*, it was shot in black and white, its leading man, Shintarô Katsu, “was not really a huge star”, and his co-star, Shigeru Amachi, “had been one of the main stars at Shintoto studios before it went bankrupt and ceased production” — surely a mixed blessing. And yet it was “a surprise hit… touch[ing] a nerve with Japanese audiences, who loved to root for the underdog.” Despite the fact our hero gives up his sword at the end of the film, Daiei produced a sequel, and… well… But enough hyperbole — what about The Tale itself? The story sees blind masseuse Zatoichi accepting an old invitation to visit an acquaintance, Sukegorô (Eijirô Yanagi). But Sukegorô is a yakuza boss, and he presses Zatoichi to join his side in a brewing war with rival Shigezô (Ryûzô Shimada) — because although he’s blind, the masseuse has legendary sword skills. On Shigezô’s side is a hired samurai, Hirate (Amachi), who Zatoichi encounters by chance. Despite the mutual respect between these two coerced warriors, the eventual gang battle comes down to a duel between them…

But enough hyperbole — what about The Tale itself? The story sees blind masseuse Zatoichi accepting an old invitation to visit an acquaintance, Sukegorô (Eijirô Yanagi). But Sukegorô is a yakuza boss, and he presses Zatoichi to join his side in a brewing war with rival Shigezô (Ryûzô Shimada) — because although he’s blind, the masseuse has legendary sword skills. On Shigezô’s side is a hired samurai, Hirate (Amachi), who Zatoichi encounters by chance. Despite the mutual respect between these two coerced warriors, the eventual gang battle comes down to a duel between them… Those prepared for a calmer, more considered film may find much to like, however. Katsu’s understated style holds your attention and makes you want to learn more about the character; not his past, necessarily, but his qualities as a man. The same is true of Amachi, in some ways even more appealing as the doomed ronin. You get a genuine sense that Zatoichi and Hirate would have had a great, long-lasting friendship if they’d met under better circumstances, which makes the manner of their encounter all the more tragic. For all the bluster about a big gang war on the horizon, it’s the relationship between these two men that forms the heart of the film.

Those prepared for a calmer, more considered film may find much to like, however. Katsu’s understated style holds your attention and makes you want to learn more about the character; not his past, necessarily, but his qualities as a man. The same is true of Amachi, in some ways even more appealing as the doomed ronin. You get a genuine sense that Zatoichi and Hirate would have had a great, long-lasting friendship if they’d met under better circumstances, which makes the manner of their encounter all the more tragic. For all the bluster about a big gang war on the horizon, it’s the relationship between these two men that forms the heart of the film. Reportedly this opener is “not the best of [the] series”, but remains “a grand introduction to the character and a touchstone for many of the themes and gags presented in the later films”.** To me, that suggests much promise for the 24 further instalments: what The Tale of Zatoichi lacks in action, it more than makes up for in character and, perhaps surprisingly, emotion. I thought it was excellent.

Reportedly this opener is “not the best of [the] series”, but remains “a grand introduction to the character and a touchstone for many of the themes and gags presented in the later films”.** To me, that suggests much promise for the 24 further instalments: what The Tale of Zatoichi lacks in action, it more than makes up for in character and, perhaps surprisingly, emotion. I thought it was excellent.

Seven Samurai used to be a striking anomaly amongst the top ten of

Seven Samurai used to be a striking anomaly amongst the top ten of  It’s also unhurried. As Kenneth Turan explains in his essay “The Hours and Times: Kurosawa and the Art of Epic Storytelling” (in the booklet for Criterion’s DVD and Blu-ray releases of the film, and available online

It’s also unhurried. As Kenneth Turan explains in his essay “The Hours and Times: Kurosawa and the Art of Epic Storytelling” (in the booklet for Criterion’s DVD and Blu-ray releases of the film, and available online  The length ensures our investment in the village, too, just as it does for the samurai. They’re not being paid a fortune — in fact, they’re just being paid food and lodging — so why do they care? Well, food and lodging are better than no food and lodging, for starters; and then, having been in the village so long in preparation, they care for it too. It is, at least for the time being, their home. You can tell an audience this, of course, but one of the few ways to make them feel it is to put them there too — and that’s what the length does. To quote from Turan again,

The length ensures our investment in the village, too, just as it does for the samurai. They’re not being paid a fortune — in fact, they’re just being paid food and lodging — so why do they care? Well, food and lodging are better than no food and lodging, for starters; and then, having been in the village so long in preparation, they care for it too. It is, at least for the time being, their home. You can tell an audience this, of course, but one of the few ways to make them feel it is to put them there too — and that’s what the length does. To quote from Turan again, the final scene, the way it’s edited and framed, ties the remaining samurai to their deceased comrades, the living and thriving farmers a distant and separate group. Fighting is the way of the past, perhaps, and peaceful farming the future. Or is the samurai’s only purpose to be found in death, because other than that they are redundant?

the final scene, the way it’s edited and framed, ties the remaining samurai to their deceased comrades, the living and thriving farmers a distant and separate group. Fighting is the way of the past, perhaps, and peaceful farming the future. Or is the samurai’s only purpose to be found in death, because other than that they are redundant? And it wasn’t as if it was overseas viewers who hit on the magic: as Turan reveals, “Toho Studios cut fifty minutes before so much as showing the film to American distributors, fearful that no Westerner would have the stamina for its original length.” The more things change the more they stay the same, I suppose — how many Great Films from Hollywood are ignored by awards bodies and audiences, only to endure in other ways?

And it wasn’t as if it was overseas viewers who hit on the magic: as Turan reveals, “Toho Studios cut fifty minutes before so much as showing the film to American distributors, fearful that no Westerner would have the stamina for its original length.” The more things change the more they stay the same, I suppose — how many Great Films from Hollywood are ignored by awards bodies and audiences, only to endure in other ways?

Box office gross is one of the methods most often used to summarise a film’s success and standing, and yet it’s one of the most useless markers of quality — and quotes like the above, from Terrence Rafferty in his article “Holy Terror” for Criterion’s Blu-ray release of Night of the Hunter (and available online

Box office gross is one of the methods most often used to summarise a film’s success and standing, and yet it’s one of the most useless markers of quality — and quotes like the above, from Terrence Rafferty in his article “Holy Terror” for Criterion’s Blu-ray release of Night of the Hunter (and available online  In another piece in Criterion’s booklet, “Downriver and Heavenward with James Agee” (online

In another piece in Criterion’s booklet, “Downriver and Heavenward with James Agee” (online  And yet, as Rafferty explains, “the most radical aspect of The Night of the Hunter… is its sense of humor. More conventional horror movies overdo the solemnity of evil. The monster in The Night of the Hunter is so bad he’s funny. Laughton and Mitchum treat evil with the indignity it deserves.” I wouldn’t say that humour is one of the film’s defining characteristics, to be honest, but it does undercut its villain. He’s not some unstoppable supernatural creature, but a man who can trip over while chasing you up the stairs, and so on. In some respects it’s this very ordinariness that makes him so scary: however much they creep you out during the film itself, you know there’s no such thing as vampires or werewolves or ghosts. There are Powells in the world, though; an everyday evil that you might not see coming, but can still get you. Brr.

And yet, as Rafferty explains, “the most radical aspect of The Night of the Hunter… is its sense of humor. More conventional horror movies overdo the solemnity of evil. The monster in The Night of the Hunter is so bad he’s funny. Laughton and Mitchum treat evil with the indignity it deserves.” I wouldn’t say that humour is one of the film’s defining characteristics, to be honest, but it does undercut its villain. He’s not some unstoppable supernatural creature, but a man who can trip over while chasing you up the stairs, and so on. In some respects it’s this very ordinariness that makes him so scary: however much they creep you out during the film itself, you know there’s no such thing as vampires or werewolves or ghosts. There are Powells in the world, though; an everyday evil that you might not see coming, but can still get you. Brr. In

In  A bomb is stuck to the underside of a car. As the vehicle pulls away, the camera drifts up into the sky, and proceeds to follow the automobile through the streets of a small Mexican border town, until it crosses the border into the US… and explodes. It’s probably the most famous long take in film history, and probably the thing Touch of Evil is most widely known for; that, and it being one of the most commonly-cited points at which the classic film noir era comes to an end.

A bomb is stuck to the underside of a car. As the vehicle pulls away, the camera drifts up into the sky, and proceeds to follow the automobile through the streets of a small Mexican border town, until it crosses the border into the US… and explodes. It’s probably the most famous long take in film history, and probably the thing Touch of Evil is most widely known for; that, and it being one of the most commonly-cited points at which the classic film noir era comes to an end. It’s like a terrible fever dream, with events and characters that sometimes seem disconnected, but nonetheless interweave through a dense plot. In this sense Welles puts us quite effectively in the shoes of Vargas and his wife — out of our depth, out of our comfort zone, out of control, struggling to keep up and keep afloat. It might be unpleasant if it wasn’t so engrossing.

It’s like a terrible fever dream, with events and characters that sometimes seem disconnected, but nonetheless interweave through a dense plot. In this sense Welles puts us quite effectively in the shoes of Vargas and his wife — out of our depth, out of our comfort zone, out of control, struggling to keep up and keep afloat. It might be unpleasant if it wasn’t so engrossing. Quinlan at all… there is not the least spark of genius in him; if there does seem to be one, I’ve made a mistake.” You can get pretentious about it all you want, and bring to bear political views that the film doesn’t support (after all, within the film Quinlan is punished for his crimes and the “mediocre” (Truffaut’s word) moral hero triumphs), but sometimes a spade is a spade; sometimes a villain is a villain; sometimes your disgusting moral perspective isn’t being covertly supported by a film that seems to condemn it.

Quinlan at all… there is not the least spark of genius in him; if there does seem to be one, I’ve made a mistake.” You can get pretentious about it all you want, and bring to bear political views that the film doesn’t support (after all, within the film Quinlan is punished for his crimes and the “mediocre” (Truffaut’s word) moral hero triumphs), but sometimes a spade is a spade; sometimes a villain is a villain; sometimes your disgusting moral perspective isn’t being covertly supported by a film that seems to condemn it. Notably and obviously absent from that list is Touch of Evil. It was taken away from Welles during the editing process, and though he submitted an infamous 58-page memo of suggestions after seeing a later rough cut, only some were followed in the version ultimately released. Time has brought change, however, and there are now multiple versions of Touch of Evil for the viewer to choose from; but whereas history often resolves one version of a film to be the definitive article, it’s hard to know which that is in this case. Indeed, it’s so contentious that Masters of Cinema went so far as to include five versions on their 2011 Blu-ray (it would’ve been six, but Universal couldn’t/wouldn’t supply the final one in HD.) The version I chose to watch, dubbed the “Reconstructed Version”, tries to recreate Welles’ vision, using footage from the theatrical cut and a preview version discovered in the ’70s to follow his notes. Despite the best intentions of its creators, this can only ever be an attempt at restoring what Welles wanted. Equally, although it was the version originally released, the theatrical cut ignores many of the director’s wishes — so as neither version was finished by Welles, surely the one created by people trying to enact his wishes is preferable to the one assembled by people who only took his ideas on advisement?

Notably and obviously absent from that list is Touch of Evil. It was taken away from Welles during the editing process, and though he submitted an infamous 58-page memo of suggestions after seeing a later rough cut, only some were followed in the version ultimately released. Time has brought change, however, and there are now multiple versions of Touch of Evil for the viewer to choose from; but whereas history often resolves one version of a film to be the definitive article, it’s hard to know which that is in this case. Indeed, it’s so contentious that Masters of Cinema went so far as to include five versions on their 2011 Blu-ray (it would’ve been six, but Universal couldn’t/wouldn’t supply the final one in HD.) The version I chose to watch, dubbed the “Reconstructed Version”, tries to recreate Welles’ vision, using footage from the theatrical cut and a preview version discovered in the ’70s to follow his notes. Despite the best intentions of its creators, this can only ever be an attempt at restoring what Welles wanted. Equally, although it was the version originally released, the theatrical cut ignores many of the director’s wishes — so as neither version was finished by Welles, surely the one created by people trying to enact his wishes is preferable to the one assembled by people who only took his ideas on advisement? To quote from Master of Cinema’s booklet, “the familiar Wellesian framing appears in 1.37:1: indeed, the “world” of the film setting emerges with little or no empty space at the top and bottom of the frame, almost certainly beyond mere coincidence.” There are things to recommend the widescreen experience (“a more tightly-wound, claustrophobic atmosphere”), and undoubtedly the debate will continue… and such is the wonders of the modern film fan that, rather than having to make do with someone else’s decision on what to put out, all the alternatives are at our fingertips.

To quote from Master of Cinema’s booklet, “the familiar Wellesian framing appears in 1.37:1: indeed, the “world” of the film setting emerges with little or no empty space at the top and bottom of the frame, almost certainly beyond mere coincidence.” There are things to recommend the widescreen experience (“a more tightly-wound, claustrophobic atmosphere”), and undoubtedly the debate will continue… and such is the wonders of the modern film fan that, rather than having to make do with someone else’s decision on what to put out, all the alternatives are at our fingertips. Ever since I read

Ever since I read  naturalistic to the point of being almost documentarian, with half-caught snatches of dialogue and sequences that seem trimmed to (almost) the relevant moments from much longer filming — still begs that you pay attention, but it seems this cut gives you more of a hand: it gets to the killing quicker (“63 vs 82 minutes”), a meeting with gangsters is “longer, more coherent and explicit”, and so on.

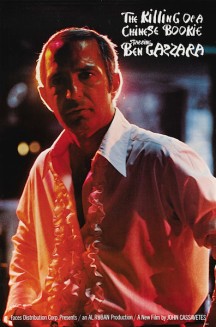

naturalistic to the point of being almost documentarian, with half-caught snatches of dialogue and sequences that seem trimmed to (almost) the relevant moments from much longer filming — still begs that you pay attention, but it seems this cut gives you more of a hand: it gets to the killing quicker (“63 vs 82 minutes”), a meeting with gangsters is “longer, more coherent and explicit”, and so on. The Killing of a Chinese Bookie is not a neat little thriller in any respect. As Tom Charity puts it (in the BFI booklet again), “if the scenario sounds generic, the film is something else”. It reminded me of Martin Scorsese’s

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie is not a neat little thriller in any respect. As Tom Charity puts it (in the BFI booklet again), “if the scenario sounds generic, the film is something else”. It reminded me of Martin Scorsese’s  Part of Leone’s intended trilogy about the history of violence in the USA, Once Upon a Time in America is the life story of four friends and gangsters in Noo Yoik during a large chunk of the 20th Century. So it’s a gangster film focusing on violence, then? Well, no… not at all, really. Indeed, saying Once Upon a Time in America is a film about gangsters is a bit like saying

Part of Leone’s intended trilogy about the history of violence in the USA, Once Upon a Time in America is the life story of four friends and gangsters in Noo Yoik during a large chunk of the 20th Century. So it’s a gangster film focusing on violence, then? Well, no… not at all, really. Indeed, saying Once Upon a Time in America is a film about gangsters is a bit like saying  Leaving aside the less savoury aspects (as, it seems,

Leaving aside the less savoury aspects (as, it seems,  Once Upon a Time in America falls somewhere between these two stools. It’s a film that is, I think, easy to instantly admire — if not wholly, then for its majority; but also one I found difficult to process a full personal reaction to. With the recently-extended version set to arrive on DVD/Blu-ray/download later this year (in the US, at any rate), an ultra-convenient chance for a second evaluation looms.

Once Upon a Time in America falls somewhere between these two stools. It’s a film that is, I think, easy to instantly admire — if not wholly, then for its majority; but also one I found difficult to process a full personal reaction to. With the recently-extended version set to arrive on DVD/Blu-ray/download later this year (in the US, at any rate), an ultra-convenient chance for a second evaluation looms.

(and it made more than double per screen what

(and it made more than double per screen what  The Doctor’s role in the Time War has not only dominated many of his actions and personalities since it happened, but it also stands awkwardly with his persona as a whole. Here’s the man who always does the right thing, always avoids violence, always finds another way, even when there is no other way… and this man wiped out all of his people and all of the Daleks? The same man who, in his fourth incarnation, stared at two wires that could erase the Daleks from history and pondered, “do I have the right?”, before concluding that he didn’t? Doesn’t really make sense, does it?

The Doctor’s role in the Time War has not only dominated many of his actions and personalities since it happened, but it also stands awkwardly with his persona as a whole. Here’s the man who always does the right thing, always avoids violence, always finds another way, even when there is no other way… and this man wiped out all of his people and all of the Daleks? The same man who, in his fourth incarnation, stared at two wires that could erase the Daleks from history and pondered, “do I have the right?”, before concluding that he didn’t? Doesn’t really make sense, does it? I think some fans would have preferred a big party history mash-up; they certainly would have liked to see their favourite faces from the past. But let’s be honest: from the classic era, only Paul McGann could pass muster as still being the Doctor he once was (and he got his own, fantastic, mini-episode to prove it); and how the hell do you construct a story with a dozen leading men? It’s clearly enough of a struggle with three. The Doctor is always the cleverest person in the room, so what do you do with multiples of him? Moffat finds ways to make all of the Doctors here (that’d be David Tennant’s 10th, Matt Smith’s 11th, and John Hurt’s newly-created ‘War Doctor’) have something to do, something to say, and something to contribute — because really, the oldest (i.e newest) Doctor should be the most experienced and have all the ideas, right? There are ways round that, but only so many.

I think some fans would have preferred a big party history mash-up; they certainly would have liked to see their favourite faces from the past. But let’s be honest: from the classic era, only Paul McGann could pass muster as still being the Doctor he once was (and he got his own, fantastic, mini-episode to prove it); and how the hell do you construct a story with a dozen leading men? It’s clearly enough of a struggle with three. The Doctor is always the cleverest person in the room, so what do you do with multiples of him? Moffat finds ways to make all of the Doctors here (that’d be David Tennant’s 10th, Matt Smith’s 11th, and John Hurt’s newly-created ‘War Doctor’) have something to do, something to say, and something to contribute — because really, the oldest (i.e newest) Doctor should be the most experienced and have all the ideas, right? There are ways round that, but only so many. Along the way, Moffat nails so many other things. The dialogue and situations sparkle, and frequently gets to have its cake and eat it: familiar catchphrases and behavioural ticks of the 10th and 11th Doctors are trotted out to a fan-pleasing extent, and then Hurt’s aged, grumpier, old-fashioned Doctor gets to criticise their ludicrousness, speaking for a whole generation of fans who hate “timey-wimey” and “allons-y” and all the rest. I think it’s this self-awareness that helps so much with selling the episode to everyone, both calling back to well-known elements of the series that many love, and pillorying their expectedness for those that aren’t so keen. Well, it would be a pretty awful party if you had a cake but couldn’t eat it, right?

Along the way, Moffat nails so many other things. The dialogue and situations sparkle, and frequently gets to have its cake and eat it: familiar catchphrases and behavioural ticks of the 10th and 11th Doctors are trotted out to a fan-pleasing extent, and then Hurt’s aged, grumpier, old-fashioned Doctor gets to criticise their ludicrousness, speaking for a whole generation of fans who hate “timey-wimey” and “allons-y” and all the rest. I think it’s this self-awareness that helps so much with selling the episode to everyone, both calling back to well-known elements of the series that many love, and pillorying their expectedness for those that aren’t so keen. Well, it would be a pretty awful party if you had a cake but couldn’t eat it, right? Smith and Jenna Coleman are on form too, of course, but as the series’ regular cast members that feels less remarkable. That’s not intended to sell them short, however, as they hold their own against actors who are arguably more, shall we say, established. If there’s one weak link it may be Joanna Page’s eyebrows, possibly the side effect of duelling with an English accent. (Complete aside: I’m rewatching Gavin & Stacey as I write this, and feel horrible even going near criticism of such a lovely person.)

Smith and Jenna Coleman are on form too, of course, but as the series’ regular cast members that feels less remarkable. That’s not intended to sell them short, however, as they hold their own against actors who are arguably more, shall we say, established. If there’s one weak link it may be Joanna Page’s eyebrows, possibly the side effect of duelling with an English accent. (Complete aside: I’m rewatching Gavin & Stacey as I write this, and feel horrible even going near criticism of such a lovely person.) Credit too to editor Liana Del Giudice, not only for crafting cinematic action sequences, but for stitching together a narrative that is often told with imagery and flashbacks, rather than people stood around chatting. Look at the sequence just after the Doctor sees the painting for the first time as just one clear example. That sequence may be dialogue-driven, but the faded-in and intercut flashbacks and glimpses of other events are what’s really conveying information. This is first-class visual storytelling, not just when compared to the rest of British TV, or international TV, or cinema, but the whole shebang.

Credit too to editor Liana Del Giudice, not only for crafting cinematic action sequences, but for stitching together a narrative that is often told with imagery and flashbacks, rather than people stood around chatting. Look at the sequence just after the Doctor sees the painting for the first time as just one clear example. That sequence may be dialogue-driven, but the faded-in and intercut flashbacks and glimpses of other events are what’s really conveying information. This is first-class visual storytelling, not just when compared to the rest of British TV, or international TV, or cinema, but the whole shebang. Still, you can’t please all of the people all of the time, and not everyone liked The Day of the Doctor: it may’ve topped DWM’s poll, but there were voters who scored it just one out of ten. But then, that’s true of 239 of the series’ 241 stories; and almost 60% of voters gave it a full ten out of ten — that’s a pretty clear consensus. I didn’t get round to voting myself, but I would’ve been amongst them. There are undoubtedly some weak spots that I haven’t flagged up, but conversely, there are myriad other successes — both minor (the opening! The dozens of sly callbacks!) and major (the use of the Zygons! Murray Gold’s music!) — that I haven’t mentioned either.

Still, you can’t please all of the people all of the time, and not everyone liked The Day of the Doctor: it may’ve topped DWM’s poll, but there were voters who scored it just one out of ten. But then, that’s true of 239 of the series’ 241 stories; and almost 60% of voters gave it a full ten out of ten — that’s a pretty clear consensus. I didn’t get round to voting myself, but I would’ve been amongst them. There are undoubtedly some weak spots that I haven’t flagged up, but conversely, there are myriad other successes — both minor (the opening! The dozens of sly callbacks!) and major (the use of the Zygons! Murray Gold’s music!) — that I haven’t mentioned either. Rather than a sequel to the poorly-received

Rather than a sequel to the poorly-received  and the end result is a moderately unique movie. OK, it doesn’t ooze originality, but nor does it feel quite like your run-of-the-mill powered-people-punch-each-other comic book yarn.

and the end result is a moderately unique movie. OK, it doesn’t ooze originality, but nor does it feel quite like your run-of-the-mill powered-people-punch-each-other comic book yarn. Talking of women, you can’t overlook Logan’s lost love, Famke Janssen’s Jean Grey. Considering the build-up pitched The Wolverine as a standalone film, with perhaps the occasional nod to the wider X-universe, including rumours of a Jean cameo, the final film is surprisingly tied-in to previous events: there’s actually loads of Jean (how? Well…), and Wolverine’s personal journey is very much grounded in the events of The Last Stand. I’m sure you could watch this without having seen or remembered a previous X-movie, because the bulk of the plot is indeed standalone, but the emotional journey is invested in what came before.

Talking of women, you can’t overlook Logan’s lost love, Famke Janssen’s Jean Grey. Considering the build-up pitched The Wolverine as a standalone film, with perhaps the occasional nod to the wider X-universe, including rumours of a Jean cameo, the final film is surprisingly tied-in to previous events: there’s actually loads of Jean (how? Well…), and Wolverine’s personal journey is very much grounded in the events of The Last Stand. I’m sure you could watch this without having seen or remembered a previous X-movie, because the bulk of the plot is indeed standalone, but the emotional journey is invested in what came before. Without seeing all the behind-the-scenes goings-on it’s difficult to know whose fault this was, but it’s equally difficult to imagine the screenplay that Darren Aronofsky (far from your regular blockbuster director) described as “a terrific script” could have concluded this way; and knowing that his replacement, James Mangold, fiddled with the script before shooting commenced… well, draw your own conclusions.

Without seeing all the behind-the-scenes goings-on it’s difficult to know whose fault this was, but it’s equally difficult to imagine the screenplay that Darren Aronofsky (far from your regular blockbuster director) described as “a terrific script” could have concluded this way; and knowing that his replacement, James Mangold, fiddled with the script before shooting commenced… well, draw your own conclusions. The Wolverine isn’t quite the movie it could have been; nor, I think, quite the one the makers hoped they were producing. Jackman has intimated since that it’s studio interference that pushes for silly-big action sequences and the like, but that fan feedback might slowly be winning them around to the things viewers actually care about. Whether that’s true or not, I guess we’ll see in the next instalment…

The Wolverine isn’t quite the movie it could have been; nor, I think, quite the one the makers hoped they were producing. Jackman has intimated since that it’s studio interference that pushes for silly-big action sequences and the like, but that fan feedback might slowly be winning them around to the things viewers actually care about. Whether that’s true or not, I guess we’ll see in the next instalment…

Once again smitten by a pretty lady, the Falcon finds himself co-opted into guarding a wealthy woman’s jewellery. But when said jewels are promptly stolen, and murders ensue, our charming hero is implicated. Who would do such a dastardly thing? And what’s going on with the DJ in the roof of the hotel?

Once again smitten by a pretty lady, the Falcon finds himself co-opted into guarding a wealthy woman’s jewellery. But when said jewels are promptly stolen, and murders ensue, our charming hero is implicated. Who would do such a dastardly thing? And what’s going on with the DJ in the roof of the hotel? Among the rest of the cast, Vince Barnett becomes the fourth actor to play the Falcon’s sidekick, Goldie; and Jean Brooks and Rita Corday each appear in their fifth Falcon films! Brooks was previously in

Among the rest of the cast, Vince Barnett becomes the fourth actor to play the Falcon’s sidekick, Goldie; and Jean Brooks and Rita Corday each appear in their fifth Falcon films! Brooks was previously in