2009 | F. Gary Gray | 118 mins | Blu-ray | 18

Law Abiding Citizen is a revenge movie with a (slight) difference: wronged man Gerard Butler isn’t just going after the two criminals who invaded his home and murdered his wife and daughter — he’s going after the legal system that let one of the men walk free.

Law Abiding Citizen is a revenge movie with a (slight) difference: wronged man Gerard Butler isn’t just going after the two criminals who invaded his home and murdered his wife and daughter — he’s going after the legal system that let one of the men walk free.

As I say, the film begins in the home of Butler’s character, an apparently quiet family man of unclear occupation (you won’t notice this first time round — why would they clarify his occupation? what would it matter? — but it does become significant later) with a wife and a young daughter. Two men break in to rob them. One is uncertain, wants to be done and gone; the other is more aggressive — he ties them up, he attempts to rape the wife, and, ultimately (and off screen) murders the wife and daughter and leaves Butler for dead.

Months later, attorney Jamie Foxx strikes a deal: one of the attackers will get a reduced sentence for informing on the other, guaranteeing him the death penalty. Butler objects but Foxx is having none of it — the deal will be done. And then we learn that it’s the objector who’ll be getting the death penalty, while the actual murderer gets the reduced sentence. Foxx goes home, to his pregnant wife, fairly sure he did the right thing.

Ten years later… Foxx’s kid is now a similar age to Butler’s when she died. He still does the same job, by the same rules.  He attends the execution of the aforementioned criminal, but something goes wrong — instead of going to sleep with a lethal injection, the attacker suffers an agonising and horrific death. Someone must have swapped the chemicals. The prosecutors’ thoughts leap to the other criminal, but I’m sure we’ve all guessed who’s really behind this. And so Butler’s sprawling revenge mission begins…

He attends the execution of the aforementioned criminal, but something goes wrong — instead of going to sleep with a lethal injection, the attacker suffers an agonising and horrific death. Someone must have swapped the chemicals. The prosecutors’ thoughts leap to the other criminal, but I’m sure we’ve all guessed who’s really behind this. And so Butler’s sprawling revenge mission begins…

Normally I don’t spend three paragraphs outlining the plot of a movie — heck, normally I don’t grant it one (plot descriptions are easy to come by these days) — but I think the setup for Law Abiding Citizen is what makes it more interesting than your regular revenge movie. Despite it looking like a simplistic action movie, we’re actually presented with a situation where there are no clear-cut heroes and villains. Butler is wronged, he wants the killers of his family to suffer — normally, this vigilante is the hero. But did the accomplice deserve such agony? And what of the legal system he sets his sights on next, murdering lawyers and judges and the like. He’s a terrorist, normally the villain. Similar goes for Foxx — he’s the attorney, the good guy, he locks up criminals… but he’s part of a corrupt system that let a guilty man go more or less free with no thought for the truth or just punishment. So he’s not exactly a clean-cut hero either.

On the issue of who the film thinks is good and who it thinks is bad, Empire’s review asserts that “Death Wish vigilantism goes too far when you no longer grasp who you are supposed to be rooting for.” But isn’t that part of the point? Oh, wait, she’s headed me off on this one: “One might argue for the defence that this is meant to be provocatively subversive, with the ‘good guys’ becoming indistinguishable from the bad. The jury doesn’t buy it.” Well, I buy it. Both the lead characters are supposedly the good guys, but both do bad things to one degree or another. The film challenges us about who to side with. Sure, some viewers will come down hard one way… but some viewers will come down hard the other. Plenty of the rest will be left somewhere in between, sympathising with the wronged man but abhorring the extremes to which he goes. And what of Foxx at the end, who on the one hand has learnt his lesson (or says he has), but on the other resorts to the same kind of violent tactics employed by his opponent. Is he in the right now? Well, I suppose he did approve of the death penalty all along. Tsk, Americans.

On the issue of who the film thinks is good and who it thinks is bad, Empire’s review asserts that “Death Wish vigilantism goes too far when you no longer grasp who you are supposed to be rooting for.” But isn’t that part of the point? Oh, wait, she’s headed me off on this one: “One might argue for the defence that this is meant to be provocatively subversive, with the ‘good guys’ becoming indistinguishable from the bad. The jury doesn’t buy it.” Well, I buy it. Both the lead characters are supposedly the good guys, but both do bad things to one degree or another. The film challenges us about who to side with. Sure, some viewers will come down hard one way… but some viewers will come down hard the other. Plenty of the rest will be left somewhere in between, sympathising with the wronged man but abhorring the extremes to which he goes. And what of Foxx at the end, who on the one hand has learnt his lesson (or says he has), but on the other resorts to the same kind of violent tactics employed by his opponent. Is he in the right now? Well, I suppose he did approve of the death penalty all along. Tsk, Americans.

There is action and violence in the film, and I’m sure that appeals to some viewers, but it’s not wholly central and not distracting from the other offerings: both the debatable morals mentioned above, and the mystery of how Butler is affecting his campaign of vengeance from within a maximum-security prison. This is where his previously-unmentioned prior occupation becomes relevant, but I won’t go that deep into the plot here. Some find the final act, where this is ultimately revealed and explained, to be a ludicrous step too far.  It is a little far-fetched, granted, but it’s not so outside the rules the film sets up for itself that I find it unacceptable.

It is a little far-fetched, granted, but it’s not so outside the rules the film sets up for itself that I find it unacceptable.

As for the violence, it can be a little extreme, but mostly it isn’t. One sequence threatens to be the definition of torture porn, but other than a verbal description we’re spared the majority of the gory details. The Director’s Cut runs about 10 minutes longer than the theatrical, and yes includes a smidgen more gore (though a graphic shot of a disembodied, mutilated head might be considered more than a smidgen), but seems to be largely made up of short character scenes and insignificant extensions to a variety of sequences. The film was cut to get an R in the US after being awarded an NC-17; this is officially released unrated, but I think we know what that means. (Both are 18 in the UK.)

Law Abiding Citizen seems to be far more popular with audiences than critics: on Rotten Tomatoes the critic score is a measly 25%, but the reader score is 77%; on IMDb it ranks 7.2; and on LOVEFiLM it has a solid four stars (and they allow half-stars). I must be more of a viewer than a critic, then, because I liked it. It is distasteful in a way, but, like its lead character, it has a point to make in a bold and attention-grabbing manner. Sure, you could make a more intelligent movie debating these points in a reasonable fashion, but you’re not going to interest the same audience — again, the same strategy employed by Butler’s character.

As an action-thriller that actually has something to think about wrapped up in it, I considered being a bit lenient in my score (much as I was to The Condemned). It’s let down by a few things though — its own far-fetchedness, especially toward the end, plus being generally overblown — so I’ve eventually gone on the lower end. Maybe I should start using half-stars after all…

As an action-thriller that actually has something to think about wrapped up in it, I considered being a bit lenient in my score (much as I was to The Condemned). It’s let down by a few things though — its own far-fetchedness, especially toward the end, plus being generally overblown — so I’ve eventually gone on the lower end. Maybe I should start using half-stars after all…

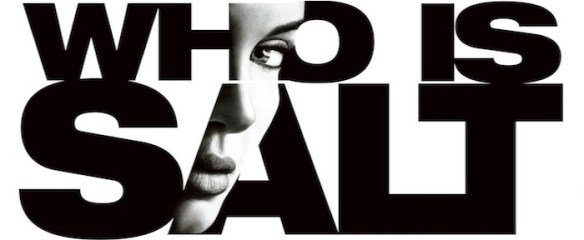

Angelina Jolie takes on a role originally earmarked for Tom Cruise in this Bourne-ish spy thriller from screenwriter Kurt Wimmer (

Angelina Jolie takes on a role originally earmarked for Tom Cruise in this Bourne-ish spy thriller from screenwriter Kurt Wimmer ( This is Salt’s mystery, and this is one of its strong points. The plot developments are well-paced throughout, developing and shifting our expectations rather than stretching it all for a glut of final act reveals. In this regard it goes places you might not expect from a mainstream Hollywood thriller. For starters, you expect the funeral-set assassination to eventually be the film’s climax, no doubt revealing our heroine isn’t a Russian spy as she unmasks the real killer. But that occurs at the halfway point, spinning the film off in new directions. To say more would spoil one of the film’s strongest elements: that, as I said, it has twists and follows storylines you wouldn’t expect in a Hollywood summer blockbuster.

This is Salt’s mystery, and this is one of its strong points. The plot developments are well-paced throughout, developing and shifting our expectations rather than stretching it all for a glut of final act reveals. In this regard it goes places you might not expect from a mainstream Hollywood thriller. For starters, you expect the funeral-set assassination to eventually be the film’s climax, no doubt revealing our heroine isn’t a Russian spy as she unmasks the real killer. But that occurs at the halfway point, spinning the film off in new directions. To say more would spoil one of the film’s strongest elements: that, as I said, it has twists and follows storylines you wouldn’t expect in a Hollywood summer blockbuster. The three cuts, then, are: Theatrical (100 minutes — this was trimmed for the UK to make 12A, but is apparently uncut on disc); Director’s Cut (the one I viewed, this is 4 minutes 5 seconds longer); and an Extended Cut (1 minute 5 seconds longer than the Theatrical). The latter is based on the Director’s Cut and I’ll come to it in a minute. The differences between the Theatrical and Director’s cuts are numerous, but mainly amount to some extra character beats (including more flashbacks to Salt’s childhood) and violence — more blood; seeing people get hit rather than just seeing Salt firing; the President is killed rather than just knocked out; plus a very different death for Salt’s husband (again, more on this in a moment). Plus there’s a voiceover ending too, which in my opinion sets up the sequel even more than the Theatrical version does, with a blatant cliffhanger and suggested plot direction. My regular comparison site

The three cuts, then, are: Theatrical (100 minutes — this was trimmed for the UK to make 12A, but is apparently uncut on disc); Director’s Cut (the one I viewed, this is 4 minutes 5 seconds longer); and an Extended Cut (1 minute 5 seconds longer than the Theatrical). The latter is based on the Director’s Cut and I’ll come to it in a minute. The differences between the Theatrical and Director’s cuts are numerous, but mainly amount to some extra character beats (including more flashbacks to Salt’s childhood) and violence — more blood; seeing people get hit rather than just seeing Salt firing; the President is killed rather than just knocked out; plus a very different death for Salt’s husband (again, more on this in a moment). Plus there’s a voiceover ending too, which in my opinion sets up the sequel even more than the Theatrical version does, with a blatant cliffhanger and suggested plot direction. My regular comparison site

She has to control her emotions so as not to give herself away. In the other versions, however, she’s presented with him in a chamber and given a choice to save him — except trying to save him would give her away, so she’s forced to watch, blank-faced, as he slowly drowns. Salt sacrifices him for the greater good; he dies seeing her cold emotionless face. Ouch. By comparison, the theatrical cut’s blunt gunshot is much softer.

She has to control her emotions so as not to give herself away. In the other versions, however, she’s presented with him in a chamber and given a choice to save him — except trying to save him would give her away, so she’s forced to watch, blank-faced, as he slowly drowns. Salt sacrifices him for the greater good; he dies seeing her cold emotionless face. Ouch. By comparison, the theatrical cut’s blunt gunshot is much softer. if the filmmakers considered another option, now we can see it, and in cases like this choose our preference. Though it seems clear, by its inclusion in both the theatrical and director’s cuts, that Noyce preferred the instant-revenge option.

if the filmmakers considered another option, now we can see it, and in cases like this choose our preference. Though it seems clear, by its inclusion in both the theatrical and director’s cuts, that Noyce preferred the instant-revenge option.

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets’ Nest — or, in America, Hornet’s Nest (oh, Americans!) — or, translated from the original Swedish, The Pipe Dream That Was Blown Up — or, according to a different translation, The Air Castle That Was Blown Up (guess that’s a cultural thing…) — is the third and final part of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy.

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets’ Nest — or, in America, Hornet’s Nest (oh, Americans!) — or, translated from the original Swedish, The Pipe Dream That Was Blown Up — or, according to a different translation, The Air Castle That Was Blown Up (guess that’s a cultural thing…) — is the third and final part of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy. while the villains futilely attempt to stop the heroes publishing everything they already seem to know.

while the villains futilely attempt to stop the heroes publishing everything they already seem to know. The other cornerstone of the film is Lisbeth’s trial for the attempted murder of her father at the end of Played with Fire. The final third of the film is dominated by a series of immensely satisfying courtroom scenes in which the defence trounce the opposition, not through American-esque grandstanding but through a quiet and thorough application of facts and truth. You can see the satisfaction bubbling under Lisbeth’s almost-static face as the prosecution unknowingly hang themselves, the defence — Mikael Blomkvist’s sister Annika, for what it’s worth — holding back her killer evidence until the prosecution have dug themselves a pit so deep even this mixed metaphor would be buried. Both Lisbeth and Annika walk all over them by remaining calm and logical, dispatching the case against Lisbeth in a way that becomes an absolute joy for the viewer.

The other cornerstone of the film is Lisbeth’s trial for the attempted murder of her father at the end of Played with Fire. The final third of the film is dominated by a series of immensely satisfying courtroom scenes in which the defence trounce the opposition, not through American-esque grandstanding but through a quiet and thorough application of facts and truth. You can see the satisfaction bubbling under Lisbeth’s almost-static face as the prosecution unknowingly hang themselves, the defence — Mikael Blomkvist’s sister Annika, for what it’s worth — holding back her killer evidence until the prosecution have dug themselves a pit so deep even this mixed metaphor would be buried. Both Lisbeth and Annika walk all over them by remaining calm and logical, dispatching the case against Lisbeth in a way that becomes an absolute joy for the viewer. It means Lisbeth remains an unknowable, elusive mystery, but then isn’t that part of what makes her so fascinating? The full exposure of her troubled (to say the least) history in this episode clears up some of her ambiguity without lessening her as a character. It’s a testament to the understated excellence of the performance that actions as little as a smile or saying “thank you” are huge revelations.

It means Lisbeth remains an unknowable, elusive mystery, but then isn’t that part of what makes her so fascinating? The full exposure of her troubled (to say the least) history in this episode clears up some of her ambiguity without lessening her as a character. It’s a testament to the understated excellence of the performance that actions as little as a smile or saying “thank you” are huge revelations. the second balances on top of the events in its predecessor. The difference is, I properly enjoyed Hornets’ Nest. I wouldn’t watch it again in isolation (unlike Dragon Tattoo, which doesn’t need its two sequels to function as a story), and perhaps it had too much going on for its own good — or perhaps I’m being too demanding of the intricacies of the investigation — but it’s a solid final episode with a lot of satisfying moments.

the second balances on top of the events in its predecessor. The difference is, I properly enjoyed Hornets’ Nest. I wouldn’t watch it again in isolation (unlike Dragon Tattoo, which doesn’t need its two sequels to function as a story), and perhaps it had too much going on for its own good — or perhaps I’m being too demanding of the intricacies of the investigation — but it’s a solid final episode with a lot of satisfying moments. Creating any kind of sequel is hard — the endless array of failed attempts is testament to that — but I think creating a direct sequel to a successful crime thriller may be the hardest.

Creating any kind of sequel is hard — the endless array of failed attempts is testament to that — but I think creating a direct sequel to a successful crime thriller may be the hardest. and they need a brand new case to become embroiled in. And it’s got to be as good as the last one, but it can’t be the same because we’ve had that mystery solved. You could have a different solution, of course; you could change some of the details, naturally; but police dramas on TV vary their types of murders every week for a reason. So in your new tale, the new characters have to be just as interesting as the first batch, the new mystery has to be just as intriguing too, and it really ought to be a notably different crime being investigated.

and they need a brand new case to become embroiled in. And it’s got to be as good as the last one, but it can’t be the same because we’ve had that mystery solved. You could have a different solution, of course; you could change some of the details, naturally; but police dramas on TV vary their types of murders every week for a reason. So in your new tale, the new characters have to be just as interesting as the first batch, the new mystery has to be just as intriguing too, and it really ought to be a notably different crime being investigated. One solution to the sequel problem is to “make it personal”, and that’s exactly what we get in The Girl Who Played with Fire. A journalist and his girlfriend working for Mikael are murdered and Lisbeth is suspected of the crime. It’s somewhere around here that the coincidences begin to pile up. It makes perfect sense as a plot in itself, but in bringing Mikael and Lisbeth back together it doesn’t work — it’s not related to their previous encounter, so it’s entirely coincidental. Coincidence is a dangerous thing in fiction; it asks your audience to accept something that doesn’t fit our logic of how stories work. It happens all the time in real life of course, but in real life a flipped coin with a 50/50 chance of being heads or tails could turn up heads twenty times in a row, but a person asked to estimate twenty results of a flipped coin will never put more than two or three of one side in a row (unless they know to subvert it… look, this isn’t the point).

One solution to the sequel problem is to “make it personal”, and that’s exactly what we get in The Girl Who Played with Fire. A journalist and his girlfriend working for Mikael are murdered and Lisbeth is suspected of the crime. It’s somewhere around here that the coincidences begin to pile up. It makes perfect sense as a plot in itself, but in bringing Mikael and Lisbeth back together it doesn’t work — it’s not related to their previous encounter, so it’s entirely coincidental. Coincidence is a dangerous thing in fiction; it asks your audience to accept something that doesn’t fit our logic of how stories work. It happens all the time in real life of course, but in real life a flipped coin with a 50/50 chance of being heads or tails could turn up heads twenty times in a row, but a person asked to estimate twenty results of a flipped coin will never put more than two or three of one side in a row (unless they know to subvert it… look, this isn’t the point). it’s never seriously looked into and, consequently, other dramas have tackled the issue with greater depth, sensitivity and insight. What Mikael and Lisbeth are actually looking into is a conspiracy of sorts around some murders. The way the trail is followed isn’t as clever as it was in Dragon Tattoo and, consequently, isn’t as interesting. The two protagonists go about their investigations independently. This is a long-held technique in novel writing — multiple strands allows the author to alternate which is followed from chapter to chapter, almost by itself providing momentum and the must-keep-reading factor as the reader has to race through the next chapter to rejoin the thread of the previous one (it’s not that simple or we’d all be churning them out… but look, I’m getting off the point again). The problem here is that Dragon Tattoo was largely at its best when the two were together, so keeping them apart is less satisfying. To top that off, they’re each finding out different things, which means as the audience we can feel a few steps ahead of the characters as we have the benefit of both sides of the case. That’s not always a bad thing, but it can be slightly disconcerting when you know the answers your hero is still searching for.

it’s never seriously looked into and, consequently, other dramas have tackled the issue with greater depth, sensitivity and insight. What Mikael and Lisbeth are actually looking into is a conspiracy of sorts around some murders. The way the trail is followed isn’t as clever as it was in Dragon Tattoo and, consequently, isn’t as interesting. The two protagonists go about their investigations independently. This is a long-held technique in novel writing — multiple strands allows the author to alternate which is followed from chapter to chapter, almost by itself providing momentum and the must-keep-reading factor as the reader has to race through the next chapter to rejoin the thread of the previous one (it’s not that simple or we’d all be churning them out… but look, I’m getting off the point again). The problem here is that Dragon Tattoo was largely at its best when the two were together, so keeping them apart is less satisfying. To top that off, they’re each finding out different things, which means as the audience we can feel a few steps ahead of the characters as we have the benefit of both sides of the case. That’s not always a bad thing, but it can be slightly disconcerting when you know the answers your hero is still searching for. Despite Lisbeth being the focus of much of the attention laden on these books/films/remakes, she’s a less engaging character when by herself. Here she shuffles around silently, digging up files that she and we stare at to reveal information. There are only a few moments for her (and, consequently, Noomi Rapace) to show off what endeared her to viewers before — her confrontation with a pair of arson-bent bikers, for instance.

Despite Lisbeth being the focus of much of the attention laden on these books/films/remakes, she’s a less engaging character when by herself. Here she shuffles around silently, digging up files that she and we stare at to reveal information. There are only a few moments for her (and, consequently, Noomi Rapace) to show off what endeared her to viewers before — her confrontation with a pair of arson-bent bikers, for instance. It also feels less filmic than the first film. Is it poor direction? Is it just the opened-up 1.78:1 ratio? I’ve read that all three films were shot like this, as they were intended for Swedish TV, meaning Dragon Tattoo’s Blu-ray is cropped to 2.35:1. You hardly ever see 2.35:1 on TV (

It also feels less filmic than the first film. Is it poor direction? Is it just the opened-up 1.78:1 ratio? I’ve read that all three films were shot like this, as they were intended for Swedish TV, meaning Dragon Tattoo’s Blu-ray is cropped to 2.35:1. You hardly ever see 2.35:1 on TV ( From the same production company that brought us the

From the same production company that brought us the  The original title translates as Men Who Hate Women, which is certainly very apt. The subject matter is grim and dark; horribly plausible, in fact. It’s unwaveringly depicted with some brutal, hard-to-watch scenes. They’re not exploitative though, as a lesser film merrily would be, and that makes them appropriate to the tale being told. Subplots about the two leads support the themes underpinning the main investigation — both about abuses of power, in different ways — justifying their apparent tangentiality, and consequently the film’s length.

The original title translates as Men Who Hate Women, which is certainly very apt. The subject matter is grim and dark; horribly plausible, in fact. It’s unwaveringly depicted with some brutal, hard-to-watch scenes. They’re not exploitative though, as a lesser film merrily would be, and that makes them appropriate to the tale being told. Subplots about the two leads support the themes underpinning the main investigation — both about abuses of power, in different ways — justifying their apparent tangentiality, and consequently the film’s length. Despite the modern stylings, dark themes and attention-grabbing characters, much of the film unfolds as a procedural whodunnit like, for instance, the Wallanders, complete with piles of red herrings and last-minute twists. This is probably why the book has sold so well and the film has taken over $100 million worldwide: it tickles the same nerves as all those ever-popular TV police dramas. Indeed, this adaptation is rooted in a television miniseries (an extended version exists as two 90-minute TV episodes) but it doesn’t look like it: it’s quite beautifully shot; not showy or stylised, but there are some lovely shots of scenery in particular.

Despite the modern stylings, dark themes and attention-grabbing characters, much of the film unfolds as a procedural whodunnit like, for instance, the Wallanders, complete with piles of red herrings and last-minute twists. This is probably why the book has sold so well and the film has taken over $100 million worldwide: it tickles the same nerves as all those ever-popular TV police dramas. Indeed, this adaptation is rooted in a television miniseries (an extended version exists as two 90-minute TV episodes) but it doesn’t look like it: it’s quite beautifully shot; not showy or stylised, but there are some lovely shots of scenery in particular. With Dragon Tattoo featuring material that seems ideally suited to the director who gave us

With Dragon Tattoo featuring material that seems ideally suited to the director who gave us  How time flies — I’ve been meaning to re-watch Zodiac ever since I

How time flies — I’ve been meaning to re-watch Zodiac ever since I  As the changes have little impact on the film’s fundamental quality, the points in

As the changes have little impact on the film’s fundamental quality, the points in  but the sheer weight of evidence the other way seems to leave little room for doubt. More so, then, is that the murders are done with before the halfway mark. That’s because it’s still following the story of the investigation, true, but a lesser filmmaker could have weighted it differently, rushing through Graysmith’s later enquiries in a speedy third act. Instead, Fincher’s focus throughout is on the people looking into the crime, and it’s as much the tale of their obsession — and what it takes to break their obsession, be it weariness or pushing through ’til the final answer — as it is the tale of a serial killer.

but the sheer weight of evidence the other way seems to leave little room for doubt. More so, then, is that the murders are done with before the halfway mark. That’s because it’s still following the story of the investigation, true, but a lesser filmmaker could have weighted it differently, rushing through Graysmith’s later enquiries in a speedy third act. Instead, Fincher’s focus throughout is on the people looking into the crime, and it’s as much the tale of their obsession — and what it takes to break their obsession, be it weariness or pushing through ’til the final answer — as it is the tale of a serial killer. and place-and-time subtitles too, but hey, sometimes you need specificity.

and place-and-time subtitles too, but hey, sometimes you need specificity.

It’s getting on for two years since I last (and first) watched most of the Alien

It’s getting on for two years since I last (and first) watched most of the Alien  (as I haven’t watched that copy, obviously), but on Blu-ray the added footage, 2003-era new effects and 2010 re-recorded audio are indistinguishable from the rest of the film.

(as I haven’t watched that copy, obviously), but on Blu-ray the added footage, 2003-era new effects and 2010 re-recorded audio are indistinguishable from the rest of the film. One of the biggest things I remember being told about Alien³, before the Special Edition, was that most of Paul McGann’s performance had been cut; that originally he had a sizeable role that justified his fourth billing, rather than his cameo-sized part in the theatrical cut. It doesn’t feel like there’s an awful lot more of him in this version, though scanning through

One of the biggest things I remember being told about Alien³, before the Special Edition, was that most of Paul McGann’s performance had been cut; that originally he had a sizeable role that justified his fourth billing, rather than his cameo-sized part in the theatrical cut. It doesn’t feel like there’s an awful lot more of him in this version, though scanning through  Unsurprisingly, therefore, they’re almost all totally underused. Charles Dance gets the biggest slice of the cake and is as good as ever, but doing little more than show their face we have Pete Postlethwaite, Phil Davis, Peter Guinness, Danny Webb (they don’t all begin with P…) Alien³ is 19 years old now, no one could’ve predicted the future; but viewed with hindsight, the volume of under-utilised talent is almost astounding.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, they’re almost all totally underused. Charles Dance gets the biggest slice of the cake and is as good as ever, but doing little more than show their face we have Pete Postlethwaite, Phil Davis, Peter Guinness, Danny Webb (they don’t all begin with P…) Alien³ is 19 years old now, no one could’ve predicted the future; but viewed with hindsight, the volume of under-utilised talent is almost astounding. It’s also, perhaps, interesting to remember this being Fincher’s first film. He might seem like an odd choice, a first-timer paling beside the experienced hands of Scott and Cameron. But that would be to forget that, for both, their Alien films were only their second time helming a feature*; and while Cameron’s previous had been sci-fi (

It’s also, perhaps, interesting to remember this being Fincher’s first film. He might seem like an odd choice, a first-timer paling beside the experienced hands of Scott and Cameron. But that would be to forget that, for both, their Alien films were only their second time helming a feature*; and while Cameron’s previous had been sci-fi (

OK, it’s far from flawless. It’s still tangled up in the over-complex ongoing story, and peppered with flashbacks, varying from flash frames to large chunks, to try to help you follow it. On the one hand that’s lazy storytelling; on the other, much welcomed — the plot would surely be impossible to navigate without it.

OK, it’s far from flawless. It’s still tangled up in the over-complex ongoing story, and peppered with flashbacks, varying from flash frames to large chunks, to try to help you follow it. On the one hand that’s lazy storytelling; on the other, much welcomed — the plot would surely be impossible to navigate without it. Following it, there’s a nicely edited closing montage. Not particularly relevant — in other entries it’s used to expose the twist, here the twist is pretty self explanatory — but it’s oddly, briefly, rewarding for those of us who’ve sat through all the films so far (and, to be frank, if you haven’t sat through the others, you’d be mad to jump on at this point). Plus there’s an intriguing post-credits scene. No idea what it means or signifies, but it’s clearly laying the groundwork for something in the future.

Following it, there’s a nicely edited closing montage. Not particularly relevant — in other entries it’s used to expose the twist, here the twist is pretty self explanatory — but it’s oddly, briefly, rewarding for those of us who’ve sat through all the films so far (and, to be frank, if you haven’t sat through the others, you’d be mad to jump on at this point). Plus there’s an intriguing post-credits scene. No idea what it means or signifies, but it’s clearly laying the groundwork for something in the future. Note: this is an Extended or Extreme or Whatever Edition again. Minor differences only, I believe, which you can find listed

Note: this is an Extended or Extreme or Whatever Edition again. Minor differences only, I believe, which you can find listed  The “extended director’s cut” (as the Blu-ray blurb describes it) of The Wolfman begins with a new CG’d version of Universal’s classic ’30s/’40s logo, the one that I’m sure opened many/most/all of their beloved classic horror movies. As well as being a self consciously cool opening shot, it’s a succinct way for director Joe Johnston to signal his intentions: this is not your modern whizzbang horror movie, but something more classically inspired.

The “extended director’s cut” (as the Blu-ray blurb describes it) of The Wolfman begins with a new CG’d version of Universal’s classic ’30s/’40s logo, the one that I’m sure opened many/most/all of their beloved classic horror movies. As well as being a self consciously cool opening shot, it’s a succinct way for director Joe Johnston to signal his intentions: this is not your modern whizzbang horror movie, but something more classically inspired. — perhaps even the totality — or plot developments and, particularly, twists are guessable far in advance. Trying to lose 16 minutes for the theatrical cut was probably a good idea, though some of my favourite moments lie amongst what was excised.

— perhaps even the totality — or plot developments and, particularly, twists are guessable far in advance. Trying to lose 16 minutes for the theatrical cut was probably a good idea, though some of my favourite moments lie amongst what was excised. feels like something I saw in some 12A blockbuster in the last half decade.

feels like something I saw in some 12A blockbuster in the last half decade. Max Von Sydow’s cameo-sized role (only found in the extended cut) is possibly the film’s best bit. Aside from the fact he’s usually good value, the relevance of the scene itself is unclear. That might sound like a problem, but I choose to see it as making the sequence — and the character — rather intriguing. The rest of the supporting cast are largely British faces recognisable from TV and similarly-sized film roles, playing the parts you’d expect them to and existing primarily as monster ready-meals. Equally, Danny Elfman’s score is disappointingly generic and clichéd, particularly so whenever the film is being the same.

Max Von Sydow’s cameo-sized role (only found in the extended cut) is possibly the film’s best bit. Aside from the fact he’s usually good value, the relevance of the scene itself is unclear. That might sound like a problem, but I choose to see it as making the sequence — and the character — rather intriguing. The rest of the supporting cast are largely British faces recognisable from TV and similarly-sized film roles, playing the parts you’d expect them to and existing primarily as monster ready-meals. Equally, Danny Elfman’s score is disappointingly generic and clichéd, particularly so whenever the film is being the same. Do you need me to tell you how great Beauty and the Beast is? I imagine not. If you’ve seen it, you’ll know. If you haven’t, you really should, and then you’ll know.

Do you need me to tell you how great Beauty and the Beast is? I imagine not. If you’ve seen it, you’ll know. If you haven’t, you really should, and then you’ll know. It’s not a bad song — not at all — but it’s a notch below the others. (There are a few more changes to the film than just adding the song, listed

It’s not a bad song — not at all — but it’s a notch below the others. (There are a few more changes to the film than just adding the song, listed