Steven Soderbergh | 90 mins | streaming (UHD) | 2.35:1 | USA / English | 15

Steven Soderbergh’s ‘retirement’ continues with another shot-on-iPhone movie (following last year’s psychological thriller Unsane), this time going direct to Netflix. Whereas Unsane made a virtue of its iPhone cinematography to heighten a disquieting, untrustworthy atmosphere, High Flying Bird forges ahead with no such baked-in excuse for its visual quality. However, similarly to Unsane, the fact it was shot on an iPhone is almost incidental, noteworthy mainly just because it’s unusual. But more on that later.

The movie is about Ray (André Holland), a basketball agent struggling to keep his players in check during a lockout… and already you’ve lost me, movie: I had to look up what a lockout is. I’m not much of a sports person, and I’m pretty sure we don’t have lockouts in British sports. Basically, best I can tell, it’s some kind of disagreement between the players (through their union) and the team owners, which results in games not being played when they should be, and people not being paid because nothing’s happening. So, it’s a bad thing, and it’s putting Ray in a bad situation — so he sets about trying to launch an “intriguing and controversial business opportunity”, to quote an IMDb plot summary.

Something like that, anyway. Frankly, it took less than two minutes for High Flying Bird to leave me feeling lost and confused, as it dives into an “inside baseball” (as the saying goes) depiction of basketball right from the off. It felt like watching a French movie without subtitles, except here the language isn’t French, it’s basketball. In fairness, I did eventually get a handle on what the overall plot was, but mostly with hindsight and not ’til quite far in — my analogy still stands for what the viewing experience was like until that point.

For fans of basketball, or at least those with some kind of knowledge of the workings of the business side of American sport, it might all be more palatable. I think there’s some good stuff in the plot and characters, but I can only say “think” because I made such a lousy fist of following what was meant to be going on half the time. The story culminates in a final twist/reveal about Ray’s actual plan. Fortunately, by that point I’d worked out (more or less) what events had happened, so I followed it — indeed, I got there ahead of it. Well, that’s because before viewing I read a comment which implied this was a heist movie (like Soderbergh’s previous work on the Oceans films or Logan Lucky), so I’d already been on the lookout for what the real con was. Nonetheless, I’m torn between whether the reveal was quite clever, or the film thinks it’s cleverer than it actually is. If I hadn’t had that heads up, maybe I would’ve been as mind-blowingly impressed as Ray’s boss seems to be when Ray reveals the real plan to him. Or maybe I wouldn’t’ve, who can say.

Unsane suggested you couldn’t make a good-looking film on an iPhone. High Flying Bird says, actually, you can. It doesn’t all look great (especially when, for example, the shot literally wobbles from something as simple as someone putting a drinks bottle down on a table), but there are some beautiful shots in here too. Unsane almost had to make a virtue of its odd look, the weirdass visuals chiming with the story of a possibly unstable mind. High Flying Bird has no such excuses, and most of the time it doesn’t need them; though some parts do still look like a first-effort student film, which is very odd coming from a director as experienced as Soderbergh (this is the 56-year-old’s 29th feature, not to mention his 39 episodes of TV).

While researching the film’s production I came across this interesting article at The Ringer, which uses High Flying Bird as a jumping off point to examine the history, increase, and future of using iPhones for professional projects. It basically contends that phone-shot films are the future for everything, and makes that sound reasonable. It’s reminiscent of the emergence of digital photography for movies: it was a big story back when Soderbergh shot Che with digital cameras (Criterion’s Blu-ray release has a half-hour documentary dedicated to it), but it was only a couple of years later that became standard for all major movies, and a few years after that it’s now noteworthy when something is actually shot on film. It seems inconceivable that one day they’ll be shooting an Avengers movie on a phone, but then it once seemed inconceivable you’d shoot a movie that big on digital video…

It’s quite hard for me to give a concise opinion of High Flying Bird. I struggled through much of it, which made for an unpleasant viewing experience. But I acknowledge some of that lies with me knowing less about basketball than the film does. But then again, is it the film’s responsibility to explain to me the things I don’t know? I did get a handle on events by the end, and if I watched the film again I expect I’d follow it better, but I also don’t feel there’s much luring me back for a second viewing.

High Flying Bird is available on Netflix now.

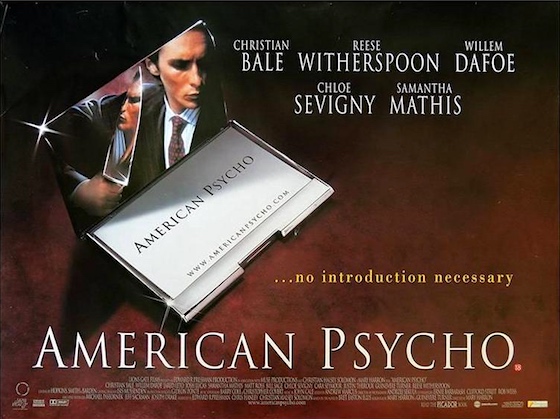

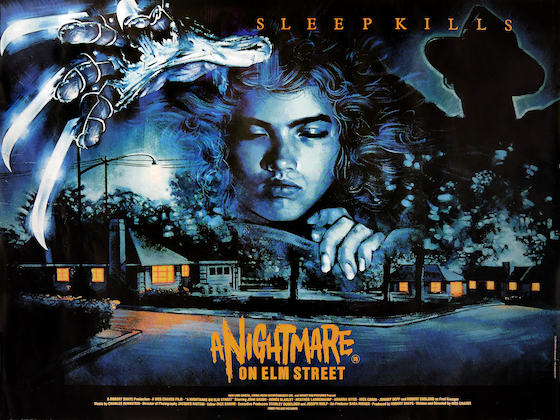

There’s an argument to be made that, from a cinematic perspective, mainstream US cinema these days is boring. Look at the kind of films American auteurs were producing in and around the studio system in the ’90s and early ’00s:

There’s an argument to be made that, from a cinematic perspective, mainstream US cinema these days is boring. Look at the kind of films American auteurs were producing in and around the studio system in the ’90s and early ’00s:  This isn’t a conceit Soderbergh uses for one scene, or wheels out now and then, but an overall approach. Some sequences are more thick with it than others, but it’s always right around the corner. It creates a unique sensation. Not disconcerting, exactly, but mysterious and querying. It has you constantly question what you’re watching — is it a memory? A plan? A fantasy? A delusion? It draws connections back and forth across the timeline of the story, bringing out thematic angles. At its most key, it helps explain what happens at the end (too bluntly for some reviewers, I should add). This collage-like style — which unlike, say, Memento’s back-to-front narrative has no obvious in-story point — will certainly not be to everyone’s taste, but it presents an interesting challenge to our usual ideas of how a film should be constructed.

This isn’t a conceit Soderbergh uses for one scene, or wheels out now and then, but an overall approach. Some sequences are more thick with it than others, but it’s always right around the corner. It creates a unique sensation. Not disconcerting, exactly, but mysterious and querying. It has you constantly question what you’re watching — is it a memory? A plan? A fantasy? A delusion? It draws connections back and forth across the timeline of the story, bringing out thematic angles. At its most key, it helps explain what happens at the end (too bluntly for some reviewers, I should add). This collage-like style — which unlike, say, Memento’s back-to-front narrative has no obvious in-story point — will certainly not be to everyone’s taste, but it presents an interesting challenge to our usual ideas of how a film should be constructed. Despite the visual trickery, The Limey still works pretty well as a straightforward thriller. You have to be prepared to accept the slippery editing, because there’s no avoiding it, but the throughline of Stamp tracking down bad men and how he deals with them is still here. Personally, I’ve never much rated Stamp as an actor, but somehow he fits here. He’s a fish out of water, a man out of place — way out of place — and possibly out of time, too, seeming like a ’60s or ’70s British gangster transported to turn-of-the-millennium L.A. It’s no discredit to the supporting cast that they mainly exist to bob around in his wake.

Despite the visual trickery, The Limey still works pretty well as a straightforward thriller. You have to be prepared to accept the slippery editing, because there’s no avoiding it, but the throughline of Stamp tracking down bad men and how he deals with them is still here. Personally, I’ve never much rated Stamp as an actor, but somehow he fits here. He’s a fish out of water, a man out of place — way out of place — and possibly out of time, too, seeming like a ’60s or ’70s British gangster transported to turn-of-the-millennium L.A. It’s no discredit to the supporting cast that they mainly exist to bob around in his wake. Matt Damon turns whistleblower (or does he?) in this amusing romp based on a true story of complicated corporate fraud.

Matt Damon turns whistleblower (or does he?) in this amusing romp based on a true story of complicated corporate fraud. Four acquaintances partake in duplicitous relationships and candid sexual discourse in writer-director Steven Soderbergh’s debut drama.

Four acquaintances partake in duplicitous relationships and candid sexual discourse in writer-director Steven Soderbergh’s debut drama. Director Steven Soderbergh takes the methodology he used to depict the drug trade in

Director Steven Soderbergh takes the methodology he used to depict the drug trade in  Steven Soderbergh’s supposed last-ever film (or, if you’re American, Steven Soderbergh’s first project after he supposedly quit film) is the story of Scott Thorson (Matt Damon), a young bisexual man in the ’70s who encounters famed flamboyant pianist Liberace (Michael Douglas) and ends up becoming his lover, which is just the start of a strange, tempestuous relationship.

Steven Soderbergh’s supposed last-ever film (or, if you’re American, Steven Soderbergh’s first project after he supposedly quit film) is the story of Scott Thorson (Matt Damon), a young bisexual man in the ’70s who encounters famed flamboyant pianist Liberace (Michael Douglas) and ends up becoming his lover, which is just the start of a strange, tempestuous relationship. It looks great, too. The film, that is, not Rob Lowe’s face. The design teams have realised an excellent recreation of the period, which is then lensed with spot-on glossy cinematography by DP

It looks great, too. The film, that is, not Rob Lowe’s face. The design teams have realised an excellent recreation of the period, which is then lensed with spot-on glossy cinematography by DP

the visual, audio, acting and plot styles of the era, why not ensure the dialogue and action follow suit? There’s no need for the violence, sex and swearing in this particular tale; at least, no need for it in a way that couldn’t be conveyed as effectively using Production Code-friendly methods. I’m uncertain if I like the film less for failing on this measure, but it does add to its inherent oddness.

the visual, audio, acting and plot styles of the era, why not ensure the dialogue and action follow suit? There’s no need for the violence, sex and swearing in this particular tale; at least, no need for it in a way that couldn’t be conveyed as effectively using Production Code-friendly methods. I’m uncertain if I like the film less for failing on this measure, but it does add to its inherent oddness. But how much do we get to know them, really? It’s easy to see why critics said “not very well”, because they’re too busy uncovering the conspiracies and revealing their part to actually show us much about themselves. But then why should that be a problem? It’s a noir thriller, not a character drama. Surely it’s about the mysteries and, if you like, the themes, rather than letting us understand the people caught up in them?

But how much do we get to know them, really? It’s easy to see why critics said “not very well”, because they’re too busy uncovering the conspiracies and revealing their part to actually show us much about themselves. But then why should that be a problem? It’s a noir thriller, not a character drama. Surely it’s about the mysteries and, if you like, the themes, rather than letting us understand the people caught up in them? production intentions rather than being invented to slot into them — provides meat on the stylistic bones.

production intentions rather than being invented to slot into them — provides meat on the stylistic bones.