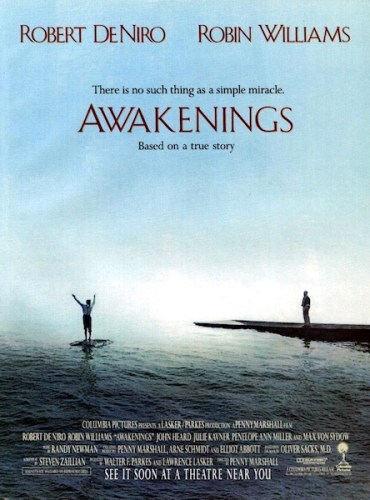

Penny Marshall | 116 mins | TV | 16:9 | USA / English | 12 / PG-13

Based on a true story, Awakenings tells of Dr Malcolm Sayer (Robin Williams), who stumbles across an element of responsiveness in previously catatonic patients on his hospital ward. Finding a condition that links them buried in their medical histories, he supposes that a newly-invented drug might help their condition, subsequently testing it on Leonard (Robert De Niro), who ‘wakes up’ for the first time in 30 years. As Sayer continues his work, the new treatment reinvigorates the lives of more people than just the patients.

I hadn’t even heard of Awakenings until the untimely passing of Robin Williams, when it was brought to my attention by Mike of Films on the Box (er, I think — I can’t find where this occurred. Either it’s on someone else’s blog or I’ve entirely misremembered the circumstances). Frankly, I’m not sure why it isn’t better remembered. Okay, it’s a little schmaltzy towards the end, but there are plenty of films that are worse for that which are held in higher esteem by some. Perhaps it’s not schmaltzy enough for those people, but still too much for people who hate that kind of thing? Or maybe it’s something else — but I don’t know what, because the rest of the film is packed with quality and subtlety.

Such qualities are to be found in its writing — a screenplay by Steven Zaillian that conveys not only the usual story, character, and emotion, but also relates medical facts and processes in a way that is expedient to the narrative but still seems genuine. Whether it is or not I couldn’t say, but I didn’t feel conned by movieland brevity. Such qualities are to be found in the directing — unshowy work by Penny Marshall which matches the screenplay for its attention to detail in a way that never makes it feel as if we’re being fed a lot of information (although we are); that finds moments of beauty and life in the humanity of the characters, their plights, their successes, and their connections.

Such qualities are to be found in the acting — De Niro’s immersive performance as a teenager trapped in a 50-year-old’s body, bookended by a medical condition so extreme that in lesser hands it could easily have become a caricature. Also Williams, giving quite possibly the most restrained performance of his career, but fully relatable as the socially inept doctor who is slowly, almost imperceptibly, brought out of his shell. And also an array of supporting performers, who each get their moment to shine in one way or another — although “shine” feels like the wrong word because, again, it’s understated. One or two moments aside (the schmaltziness I mentioned), there’s no grandstanding here.

Combine those successes with the knowledge that this is a true story (heck, you wouldn’t believe it if it weren’t) only makes the film’s events — and its messages about being attentive of others and embracing the life we’re given — all the more powerful.

I normally aim for a “critical” (for want of a better word) rather than “bloggy” (for want of a better word) tone in my reviews, just because I do (that’s in no way a criticism of others, etc). Here is where I fail as a film writer in that sense, though, because I’m not even sure how I’m meant to review Terry Gilliam’s dystopian sci-fi satire Brazil, a film as famed for its storied release history as for the movie itself.

I normally aim for a “critical” (for want of a better word) rather than “bloggy” (for want of a better word) tone in my reviews, just because I do (that’s in no way a criticism of others, etc). Here is where I fail as a film writer in that sense, though, because I’m not even sure how I’m meant to review Terry Gilliam’s dystopian sci-fi satire Brazil, a film as famed for its storied release history as for the movie itself. I’m sure there’s a thorough list of differences somewhere, but one good anecdote from Gilliam’s audio commentary tells how the ‘morning after’ scene was cut from the European release so last-minute that it was literally physically removed from the premiere print. (Gilliam regretted it immediately and it was restored for the video release.)

I’m sure there’s a thorough list of differences somewhere, but one good anecdote from Gilliam’s audio commentary tells how the ‘morning after’ scene was cut from the European release so last-minute that it was literally physically removed from the premiere print. (Gilliam regretted it immediately and it was restored for the video release.)

It would be boring if we all liked the same stuff, wouldn’t it? I’m sure there’s at least one ‘universally’-loved classic that we each dislike. Heck, tends to be every ‘universally’-loved classic has at least one Proper Critic that dislikes it. The flip side of this is that, in my opinion, if you don’t like something that everyone else does, there’s a fair chance it’s you who’s missing something. That’s a rule I apply to others, naturally, but I also try to bear it in mind myself (and, at the risk of sounding terribly arrogant, I think a few more people could do with thinking the same).

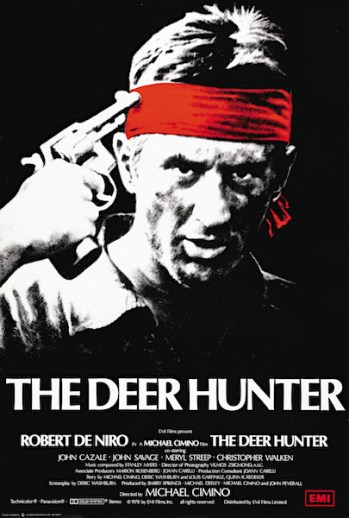

It would be boring if we all liked the same stuff, wouldn’t it? I’m sure there’s at least one ‘universally’-loved classic that we each dislike. Heck, tends to be every ‘universally’-loved classic has at least one Proper Critic that dislikes it. The flip side of this is that, in my opinion, if you don’t like something that everyone else does, there’s a fair chance it’s you who’s missing something. That’s a rule I apply to others, naturally, but I also try to bear it in mind myself (and, at the risk of sounding terribly arrogant, I think a few more people could do with thinking the same). The aforementioned fights, on the other hand, are full-on Cinema, and glorious for it. The make-up is also very good. Relatedly, De Niro’s physical transformation, from lithe boxer to washed-up fatso, is remarkable. Decades before the likes of Christian Bale and his

The aforementioned fights, on the other hand, are full-on Cinema, and glorious for it. The make-up is also very good. Relatedly, De Niro’s physical transformation, from lithe boxer to washed-up fatso, is remarkable. Decades before the likes of Christian Bale and his  Based on where we find him at the end, I guess LaMotta would appreciate a Shakespeare quotation. For all the film’s “greatest of all time” acclaimedness, this is the one that came to my mind:

Based on where we find him at the end, I guess LaMotta would appreciate a Shakespeare quotation. For all the film’s “greatest of all time” acclaimedness, this is the one that came to my mind:

Multi-hyphenate Robert Rodriguez takes his

Multi-hyphenate Robert Rodriguez takes his  to fleetingly include something that ‘needs’ to be there purely because it was in that trailer.

to fleetingly include something that ‘needs’ to be there purely because it was in that trailer.

These days perhaps even more praised than

These days perhaps even more praised than  Much praised, discussed and quoted, Taxi Driver needs little introduction. The weight of expectation also makes it hard to judge when first viewed.

Much praised, discussed and quoted, Taxi Driver needs little introduction. The weight of expectation also makes it hard to judge when first viewed.