Forbidden Planet (1956)

District 9

(2009)

2017 #88

Neill Blomkamp | 112 mins | Blu-ray | 1.85:1 | South Africa, USA, New Zealand & Canada / English | 15 / R

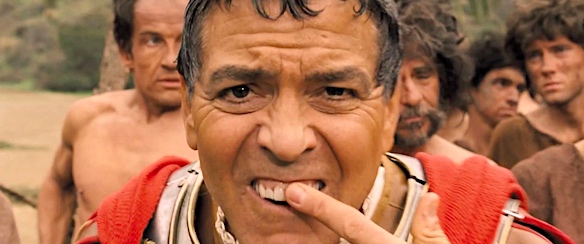

We begin this roundup with two 2009 sci-fi thrillers that made the names of their respective directors. District 9 got the wider attention, being backed by Peter Jackson and receiving a Best Picture Oscar nomination (alongside three other nods), but I’d argue it’s ultimately the lesser of the two films.

Although District 9 remains highly praised, co-writer/director Neill Blomkamp’s next two movies — Elysium and Chappie — haven’t gone down so well. Having seen both of those first, I feel like there are a lot of structural and tonal similarities between all three films, so it’s interesting to me how poorly the next two were received. Basically, they all start with some kind of societal sci-fi issue, explore that for a bit as the world of the story is established, then transition into being a shoot-em-up actioner.

In District 9’s case, it starts out as a documentary about (effectively) alien refugees who live in a segregated community in South Africa. The obvious real-world parallels are, well, obvious. Then events transpire which make the idea of having to identify with those who are Other than us — of becoming affected by their culture — very literal. Then it turns into an achieve-the-MacGuffin shoot-em-up runaround. It’s done well for what it is, with some strikingly gruesome weaponry to give the well-staged shootouts a different edge, but that’s still what it is. Presumably it was all the rather-obvious allegory stuff that helped land the film a Best Picture nomination, and the fact the second half is a not-that-original humans-vs-aliens shooter was overlooked.

For me, the clunkiest bit is the storytelling style it adopts. It’s a mockumentary… until it decides it doesn’t want to be so that it can tell its story more effectively… but then it sometimes slips back into mockumentary later on, most notably at the end. I found that distracting and formally inconsistent. I’d rather it had kept up the mockumentary act throughout or not used it at all; or, if you’re going to do both documentary and ‘reality’, have a point to it — show differing versions of the truth, that kind of thing, don’t just mix it together willy-nilly.

All told, I found District 9 to be a mixed bag. The first half is excitingly original and interestingly ideas-driven, with allegory that is powerful if perhaps a little heavy-handed (I suppose that’s kind of unavoidable when you make a movie about segregation and set it in South Africa). The second half is just a shoot-em-up.

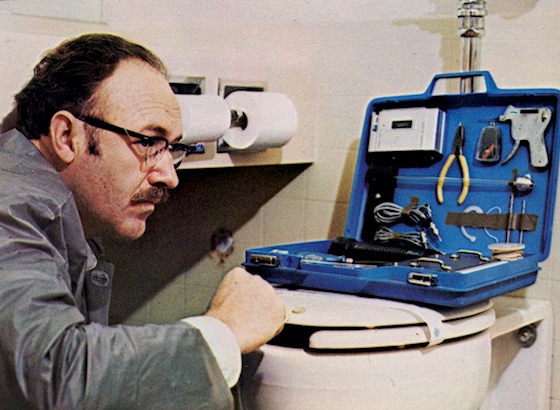

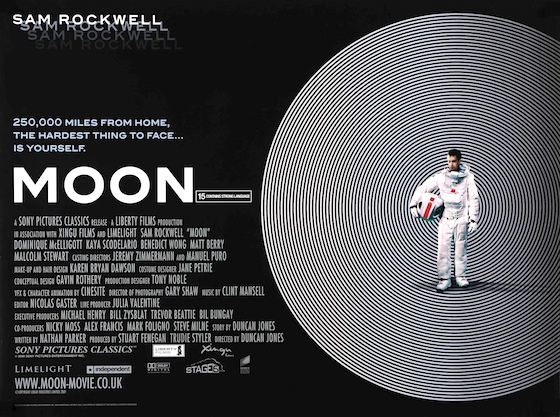

Moon

(2009)

2017 #145

Duncan Jones | 97 mins | Blu-ray | 2.40:1 | UK / English | 15 / R

The other 2009 sci-fi debut feature was that of director Duncan Jones. Although it received no Oscar love it did get a BAFTA, but seems to remain less seen: it has almost half as many user ratings on IMDb as District 9. Personally, I thought it was the superior film.

It stars Sam Rockwell as the sole inhabitant of a mining facility on the Moon. As the end of his tour of duty approaches, his investigation in a malfunction unearths a startling secret. To say any more would spoil things, though Moon gets to its reveal pretty speedily. Also, you may’ve guessed it from the trailers (I more or less did). Also, it’s nine years old now and you’ve probably seen it — though, as those IMDb numbers show, maybe not.

If you haven’t, it’s definitely worth seeking out. Like so much good sci-fi, it uses its imagined situation as impetus to explore the effect on its characters (or, in this case, character) and what the human reaction would be in such a situation. Maybe this is becoming a cliché already, but it’s quite like an episode of Black Mirror in that regard. (Isn’t all sci-fi that puts a high concept through the ringer of human experience “like Black Mirror”? Such stuff existed before that series. That said, maybe there wasn’t as much of it.)

Jones marked himself out as a director to watch with his attentiveness to character in the midst of his SF setting, but also by helming an excellently realised production on a tight budget — the moonbase set looks great and the model effects are perfect. A major reason I reckon it’s clearly better than District 9 is this consistency of style and tone. It’s a film that better knows what it wants to be and how to achieve its intended effect.

As for Jones, he went on to make Source Code, a solid follow-up, but then seemed to throw a lot of talent away on the risible Warcraft. Hopefully his forthcoming Netflix Original, Mute, will restore the balance.

Her

(2013)

2017 #165

Spike Jonze | 126 mins | Blu-ray | 1.85:1 | USA / English | 15 / R

If Moon is “a bit like an episode of Black Mirror”, Spike Jonze’s Her virtually is one. Set in a highly plausible near future — which has clearly been developed from our current obsession with our phones, iPads, digital assistants, etc — it stars Joaquin Phoenix as Theodore, a lonely chap who gets a new operating system based around a genuine AI, Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson). As Samantha develops, she and Theodore soon become friends, and then more.

People often refer to the template of Black Mirror as “what if technology but MORE”, and Her definitely fulfils that brief: “what if Siri was genuinely intelligent and someone fell in love with her?” Also like an episode of Black Mirror, it’s as much about what this reveals about humanity as it is about the crazy sci-fi concept. It’s primarily a romance about a lonely guy who was hurt in the past finding a new connection, with the fact he’s falling in love with a piece of technology almost secondary. Even within the world of the film, he’s not some kind of outcast: we hear about other people who’ve fallen for their AI, and his friends unquestioningly accept his relationship as genuine.

Such acceptance doesn’t translate into our current world, it seems. Although Her is generally very well liked, some people struggle to engage with it at all, and from what I can tell that mostly stems from them not being able to relate to Theodore and his situation, i.e. the very concept of falling in love with an AI is too impossible for them to even imagine. I can’t help but feel that says more about those viewers (for good or ill) than it does the film, which executes the storyline with a great deal of believability and heart.

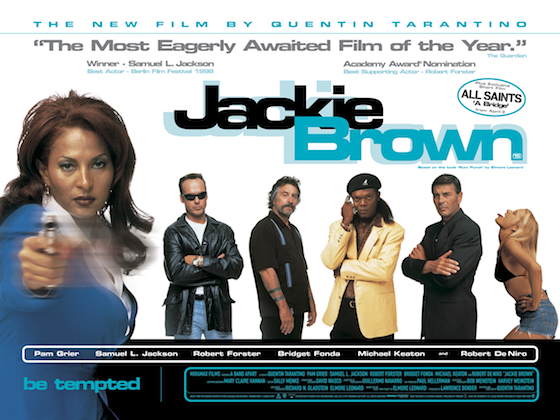

Forbidden Planet

(1956)

2017 #172

Fred McLeod Wilcox | 98 mins | Blu-ray | 2.40:1 | USA / English | U / G

This classic sci-fi adventure sees a spaceship crewed by blokes (led by Leslie Nielsen) land on the planet Altair IV to investigate what happened to a previous mission there. They find it inhabited only by Dr Morbius (Walter Pidgeon), his robot servant Robby, and his beautiful daughter Altaira (Anne Francis), who perpetually wears short skirts and has a fondness for skinny-dipping. Turns out the crew are a right bunch of horndogs (they spend most of their time lusting after Altaira, tricking her into kissing them and stuff like that), but there are bigger problems afoot when the planet starts trying to kill them.

Once it gets past everyone’s lustfulness (it feels uncomfortably like watching the filmmakers play out some personal fantasies), there are proper big sci-fi ideas driving Forbidden Planet. There are also some gloriously pulpy action sequences, like a fight against an invisible monster. It’s backed up by great special effects. Obviously they’ve all dated in one way or another, but much of it still looks fantastic for its time — the set extensions, in particular, are magnificent.

Something I wasn’t expecting (but I’m certainly not the first to note) is how blatantly the film was an influence on Star Trek. You can even map the similarities between characters pretty precisely. Switch out the spaceship models and original-flavour Star Trek is all but Forbidden Planet: The Series.

Although its gender politics have aged even less well than its special effects, and its story occasionally gets bogged down by stretches of explanatory dialogue (it sometimes feels like you’re watching the writer invent and explain his ideas in real-time), Forbidden Planet remains a mostly enjoyable SF classic.

District 9 and Forbidden Planet were viewed as part of my Blindspot 2017 project, which you can read more about here.

Moon and Her were viewed as part of my What Do You Mean You Haven’t Seen…? 2017 project, which you can read more about here.

1991 Academy Awards

1991 Academy Awards

Set in Chicago during the Great Depression, The Sting follows a young street-level con artist (Robert Redford) as he seeks revenge for his murdered partner by teaming up with a seasoned big-con pro (Paul Newman) to scam the mob boss responsible (Robert Shaw).

Set in Chicago during the Great Depression, The Sting follows a young street-level con artist (Robert Redford) as he seeks revenge for his murdered partner by teaming up with a seasoned big-con pro (Paul Newman) to scam the mob boss responsible (Robert Shaw). By many accounts this is the greatest film I’d never seen (hence it being this year’s pick for #100). How are you meant to go about approaching something like that? Probably by not thinking about it too much. I mean, something will always be “the greatest you’ve never seen”, even if you dedicate yourself to watching great movies and the “greatest you’ve never seen” is something pretty low on the list… at which point I guess it stops mattering.

By many accounts this is the greatest film I’d never seen (hence it being this year’s pick for #100). How are you meant to go about approaching something like that? Probably by not thinking about it too much. I mean, something will always be “the greatest you’ve never seen”, even if you dedicate yourself to watching great movies and the “greatest you’ve never seen” is something pretty low on the list… at which point I guess it stops mattering. Hollywood is notorious for adapting novels by grafting on happier endings, but here they did the opposite, removing even the glimmers of justice that the novel offers. In the book (according to Wikipedia), when McMurphy strangles Ratched he also exposes her breasts, humiliating her in front of the inmates; when she returns to work, her voice — her main instrument of control — is gone, and many of the inmates have either chosen to leave or have been transferred away. Conversely, in the film there is no humiliation, and we explicitly see that she still has her voice and that all the men are still there. Of course, McMurphy’s ultimate end isn’t cheery in either version. It’s almost like the anti-

Hollywood is notorious for adapting novels by grafting on happier endings, but here they did the opposite, removing even the glimmers of justice that the novel offers. In the book (according to Wikipedia), when McMurphy strangles Ratched he also exposes her breasts, humiliating her in front of the inmates; when she returns to work, her voice — her main instrument of control — is gone, and many of the inmates have either chosen to leave or have been transferred away. Conversely, in the film there is no humiliation, and we explicitly see that she still has her voice and that all the men are still there. Of course, McMurphy’s ultimate end isn’t cheery in either version. It’s almost like the anti-