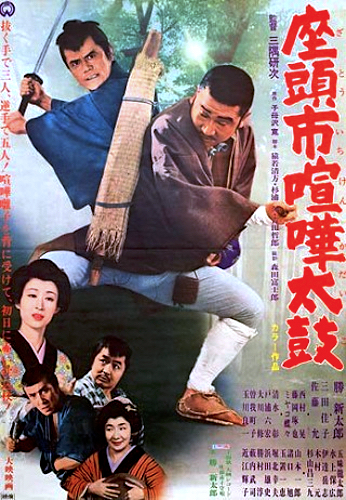

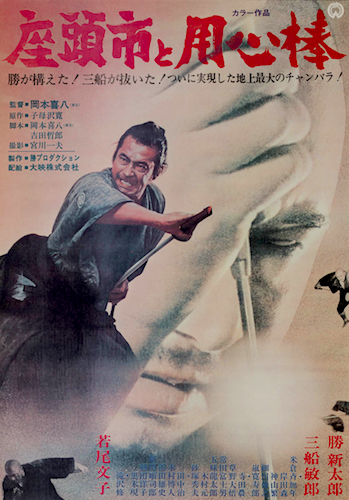

aka Zatôichi to Yôjinbô

2019 #60

Kihachi Okamoto | 116 mins | Blu-ray | 2.35:1 | Japan / Japanese | 12

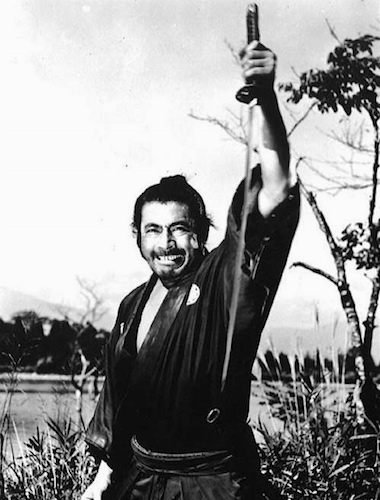

Having released anything up to four films a year for seven years, the Zatoichi series took 1969 off (apparently producer/star Shintaro Katsu had some other projects to focus on). But when it returned in 1970 it was with a big gun: as the title indicates, the main guest star for this film is the lead character from Akira Kurosawa’s films Yojimbo and Sanjuro, played by the great Toshiro Mifune. I don’t know if that was a deliberate move to mark the series’ 20th movie or if they weren’t even conscious of the milestone, but it certainly feels like it was meant to be a special occasion. “Meant to be” being the operative part of that sentence, because the result is sadly one of the least enjoyable entries in the series so far.

The film sees Ichi (Katsu) return to his hometown, which has rather gone to the dogs thanks to a local yakuza gang. Never one to just stand back or move along, Ichi ends up embroiled in the arguments between a powerful merchant (Osamu Takizawa) and his two wayward sons, one a yakuza boss (Masakane Yonekura), the other an employee of the government mint (Toshiyuki Hosokawa), who’s up to some kind of shenanigans with the gold that drives the plot… I think. Mifune’s character factors into all this as a ronin who’s been hired by the yakuza son to protect him, or kill his father, or something along those lines.

As you may have gathered, the plot here is by turns confusing and dull — one of those that loses you so thoroughly you just want to give up on trying to work it out. It has something to do with the people who make gold coins making them less well, and a hidden bar of gold that has something to do with that somehow, and a bunch of spies and stuff who are all looking for the gold bar, and some kind of feud or rivalry or disagreement between the local yakuza and Takizawa’s businessman, which may or may not have nothing to do with all the gold stuff… I think. This wouldn’t be the first Zatoichi film with an underwhelming or unintelligible plot, but it tells it with so little verve, and with so few entertaining distractions (there’s not much action, and even less humour), that there’s nothing to make up for it.

And to add insult to injury, the titular concept of the movie is a bait and switch: Mifune is not actually playing the character from Kurosawa’s films. “Yojimbo” means “bodyguard”, so it’s not like, say, casting Sean Connery in a film and calling it Meets James Bond only to have him play some unrelated character, but the promise of the title is clear and unfulfilled. It’s not like Mifune is playing an off-brand knock-off, either: he happens to be fulfilling the same job as bodyguard so that everyone can keep calling him yojimbo, but his actual name is Taisaku Sasa (not Sanjuro, as in Kurosawa’s films) and his character is nothing like his role in Kurosawa’s films (he doesn’t even look the same!) Seeing Zatoichi go head-to-head with the ‘real’ Yojimbo, with all his cunning scheming, could’ve been great. Instead, while Sasa is still a skilled swordsman, he’s a bit pathetic — lovelorn and, it would seem, not actually very good at his real job (which, as it turns out, is spying). Some of the scenes between Katsu and Mifune are good, at least. Not all of them, but some is better than none, I suppose. Ultimately, however, it’s one of the biggest disappointments in a film filled with them.

There’s plenty to be filled, too, because this is by far the longest of the original Zatoichi films: the others average 87 minutes apiece, making Meets Yojimbo a full half-hour longer than normal, and almost 20 minutes longer than even the next longest. There’s quite an extensive supporting cast, bringing with them all the varied subplots that having so many characters entails. Whether that’s what produced the extended running time, or whether an extended running time was desired so they shoved all those extra people in, I don’t know. It’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg situation, because either way the result is a jumble that I don’t think was a good idea. Few of them have an opportunity to leave a mark — there’s too much going on, and we’re all here for Mifune and Katsu anyway.

Eventually the story comes down to a simple, familiar message: “greed is bad”. The much-desired gold bar turns out to be hidden as gold dust, which ends up blowing away in the wind. It’s almost fitting and symbolic… except it only happens once most of the cast are dead or past it anyway, so it doesn’t necessarily symbolise much. I mean, there’s hardly anyone left to notice it happen. And it’s followed by a final scene that, like most of the rest of the plot, left me slightly confused. The town blacksmith tells yojimbo that Ichi isn’t motivated by gold… then we see Ichi realise his pouch of gold dust has been cut and emptied, so he scrabbles around in the dirt searching for the rest (which has blown away), when Mifune joins him. “You too?” “Just like you,” they say. And then they go their separate ways. So… they are motivated by gold? Or… they’re not, because it’s gone and they… aren’t? I don’t know if I’m being dim, or if the film bungled its own message, or if it just doesn’t have anything to say. It could be no deeper than a straight-up samurai adventure movie, of course. It would be better if it were.

This is the only Zatoichi film for director Kihachi Okamoto, who apparently was a prestige hire. I don’t think he did a particularly good job, to be honest. There’s the muddled plot, as discussed, which unfurls at a slow pace. The action scenes, often such a highlight, aren’t particularly well shot. It’s visually a very dark film, which kinda matches the grim tone, but is arguably taken too far. As Walter Biggins puts it at Quiet Bubble, “murk dominates. People wears blacks and browns. Eyes are cold, haunted, even in daytime[…] Even supposedly well-lit interiors look like homages to Rembrandt. This is a world half-glimpsed, that we squint at”. It was shot by cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, who worked on numerous Japanese classics and several other Zatoichi movies — I praised his work on Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold, for example. It’s not that what he’s done here is bad per se — there are certainly some nice individual shots, particularly around the climax — but, well, there were clearly some choices made about lighting and the colour palette.

I knew going in that Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo isn’t a particularly well regarded film, but I held out hope it was one of those occasions where I’d find the consensus wrong. Unfortunately, it wasn’t. In fact, it’s arguably the worst film in the series. It’s not just that it’s a poor Zatoichi film (which it is), it’s that it should’ve been a great one, showcasing the meeting of two top samurai heroes and the charismatic actors who play them. There may be outright lesser films in the Zatoichi series than this, but none could equal the crushing disappointment it engenders.

For what it’s worth, Katsu and Mifune co-starred in another samurai movie the same year, Machibuse, aka Incident at Blood Pass. I’ve heard it’s a lot better, so I’ll endeavour to review it at a later date.

2019 Academy Awards

2019 Academy Awards