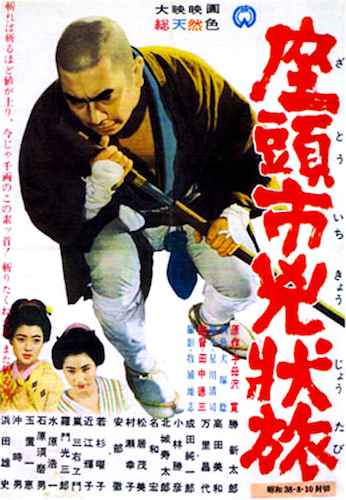

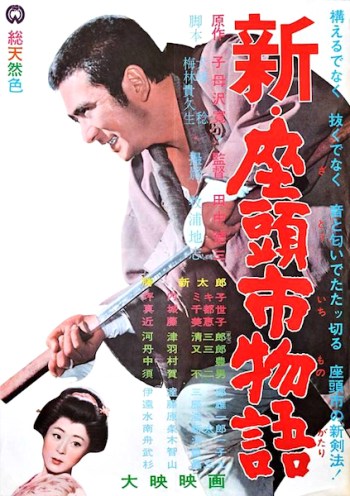

Kazuo Ikehiro | 82 mins | Blu-ray | 2.35:1 | Japan / Japanese

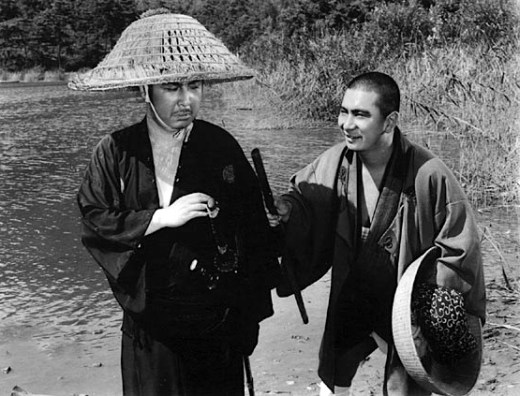

The sixth film in the Zatoichi series (and the first of four released in 1964) begins with blind masseur Ichi (Shintaro Katsu) paying tribute at the grave of a man he killed (Ichi must spend most of his time pinballing from one such grave to another). Afterwards he stumbles upon a group of celebrating villagers — they’ve finally managed to scrape together enough money to pay the taxman the thousand ryo they owe. But when that money is stolen, Ichi happens to be in the wrong place at the wrong time and is accused of being involved in the theft. He sets out to clear his name — and, despite the abuse they hurl his way, also get the villagers their money back, because he’s that kind of fella.

What unfurls is one of the series’ typically fiddly plots, characterised by a shortage of explanation about who’s who, meaning it requires attention to work out what’s going on sometimes. I’m beginning to wonder if this is a cultural issue; by which I mean, would these stories be easier to follow for Japanese viewers? Or is it just a particular feature of the Zatoichi series’ plots? Mind you, other reviews note how straightforward the story is this time out. Perhaps the problem is just getting to grips with who’s who — these films don’t always lay that out neatly. Once you have a handle on that then, yes, Chest of Gold’s story is pretty linear. It does try to play something of a twist about who’s behind the theft of the money, but that revelation shouldn’t come as a great surprise.

None of this is to say Chest of Gold is a poor film. Far from it. For one thing, it’s probably the most artfully directed Zatoichi film so far. Or if not artfully then certainly energetically — it’s full of more unusual angles and editing tricks than the previous films put together. But director Kazuo Ikehiro isn’t just a show-off, knowing when to not over-complicate matters: if a sequence calls for a simpler series of shots (in a dialogue scene, for example) then that’s what we get. The cinematography looks superb too, with a palpable richness. It was lensed by Kazuo Miyagawa, who also shot Rashomon and Yojimbo for Akira Kurosawa and Ugetsu Monogatari and Sansho Dayu for Kenji Mizoguchi, amongst other noteworthy work. When you hire the best, etc.

Their talents extend to filming the action scenes, which are some of the series’ best. They’re brief but furious, especially one where Ichi takes down a convoy of executioners, including a compliment of musketeers, filmed in a single take with a simple pan. Such understated filming lets Katsu’s combat choreography be front and centre. There’s an unexpected and quite vicious epilogue fight scene too, described by Chris D. in his Criterion notes as “one of the highlights of the series”. That’s against Jushiro, one of the series’ greatest villains, who’s just as menacing when comparing Ichi to a worm as he is when wielding his whip or sword. He’s played by Tomisaburo Wakayama, who previously appeared as the second film’s antagonist, but is a different character here.

It’s quite a brutal and adult film all round, actually: there’s blood spurting all over the place in several of the fight scenes (a first for the series); a sequence where three of the villagers are cruelly tortured; and a somewhat risqué scene where our masseur hero gets a special kind of massage himself, from a very obliging woman who, to Ichi’s surprise, expects payment after… though when he gets a whiff of her hand…

Chest of Gold doesn’t deviate from the Zatoichi formula so much that it feels out of place, but it does have enough unique and memorable elements to mark it out. It’s the series’ best entry since the first, and, based on other reviews and rankings, seems likely to remain near the top of the list.

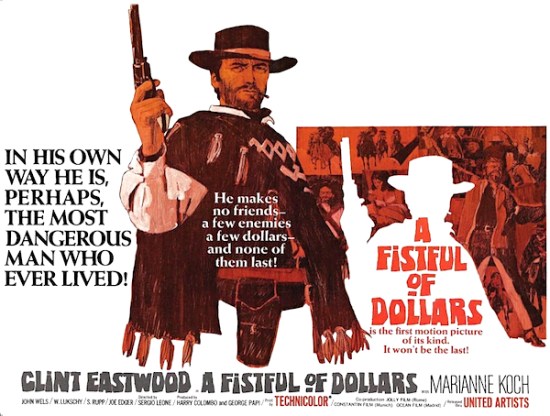

Described in the booklet accompanying the Ultimate Edition DVD release as “the last great American western before Sergio Leone reinvented the genre,” The Magnificent Seven doesn’t feel as dated as that might make it sound. Famously, it’s a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s

Described in the booklet accompanying the Ultimate Edition DVD release as “the last great American western before Sergio Leone reinvented the genre,” The Magnificent Seven doesn’t feel as dated as that might make it sound. Famously, it’s a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s  With even less screen time to go round than in Kurosawa’s original, the cast only get to provide thumbnail sketches of their characters. However, bearing that in mind, only Vaughn really feels shortchanged on time, while McQueen manages to steal every scene he’s in, even when he was supposed to just be in the background — much to Brynner’s annoyance. One reason this works is because the seven represent more or less the same things thematically, in some respects functioning as one hero character with seven parts. They are all unsettled drifters, good at killing but not at settling down; they have nothing to do but win and so be damned to go find another cause, or die trying. This is taken from Kurosawa’s film too, of course, but it fits just as well in its new setting, and the main scene where the seven discuss it is a definite highpoint of the movie.

With even less screen time to go round than in Kurosawa’s original, the cast only get to provide thumbnail sketches of their characters. However, bearing that in mind, only Vaughn really feels shortchanged on time, while McQueen manages to steal every scene he’s in, even when he was supposed to just be in the background — much to Brynner’s annoyance. One reason this works is because the seven represent more or less the same things thematically, in some respects functioning as one hero character with seven parts. They are all unsettled drifters, good at killing but not at settling down; they have nothing to do but win and so be damned to go find another cause, or die trying. This is taken from Kurosawa’s film too, of course, but it fits just as well in its new setting, and the main scene where the seven discuss it is a definite highpoint of the movie. That’s not something that bothered me, but where I did find it suffering was in comparison to Kurosawa. While it has obviously been rejigged for its new setting, it’s not just borrowed the basic concept of seven violence-skilled loners defending a needy village, but rather retained all the bones of the samurai original. As with most remakes, it falters by not doing the same thing quite as well, for one reason or another. Still, if it is a faded copy then at least it’s of one of the greatest films ever made, which leaves it a mighty fine Western in its own right.

That’s not something that bothered me, but where I did find it suffering was in comparison to Kurosawa. While it has obviously been rejigged for its new setting, it’s not just borrowed the basic concept of seven violence-skilled loners defending a needy village, but rather retained all the bones of the samurai original. As with most remakes, it falters by not doing the same thing quite as well, for one reason or another. Still, if it is a faded copy then at least it’s of one of the greatest films ever made, which leaves it a mighty fine Western in its own right. In this lesser sequel to

In this lesser sequel to