When Andy Williams sang “it’s the most wonderful time of the year”, he was on about Christmastime; but ’round these parts, the real most wonderful time of the year comes a little later: in early January, with the annual statistics post. And, friends, that time is here again.

Before the onslaught of numbers and graphs begin, a couple of quick reminders. Primarily: these stats cover my first-time feature film watches from 2024, as listed here. Shorts and rewatches are only factored in when expressly mentioned.

Secondly, and finally: as a Letterboxd Patron member, I get a yearly stats page there too, which can be found here. The numbers will look a bit different, because I also log whatever TV I can, plus it factors in shorts and rewatches more thoroughly, but that’s part of what makes it interesting as an addition/alternative to this post. It also breaks down some interesting things not covered here, like my most-watched and highest-rated stars and directors.

Now, without further ado, here’s what you came for…

I watched 131 feature films for the first time in 2024. That puts it right in the middle of the history of 100 Films: out of 18 years, it ranks ninth largest (or tenth smallest).

Of those 131 films, 85 counted towards my 100 Films in a Year Challenge. Alongside 15 rewatches, that means I finally reached all 100 films for my Challenge for the first time in its new form. More thoughts about that in the Final Standing and December review posts.

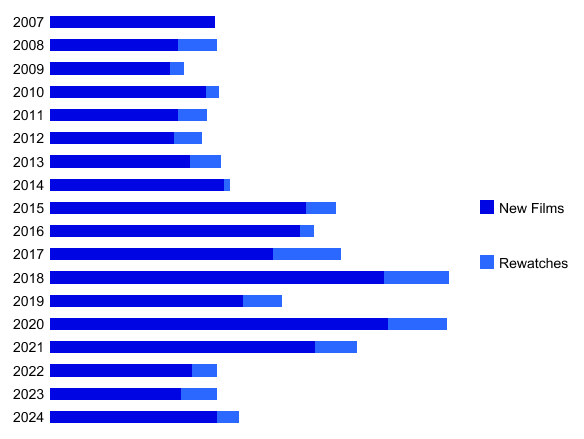

Outside of the Challenge, I rewatched only two further films for a total of 17 rewatches. That’s my lowest number since 2016, which was the last year before I started to make a concerted effort to up my rewatches (first with the Rewatchathon from 2017 to 2020, then by including them as a category in my Challenge). Any number going down is a shame, but there are always going to be compromises somewhere — if I’d rewatched more, I likely would’ve watched fewer new films.

NB: I have no rewatch data for 2007 and only incomplete numbers for 2008.

Here’s how that viewing played out across the year, month by month. The dark blue line is my first-time watches and the pale blue is rewatches. Both lines are much flatter than normal (I mean, look at 2023’s), which is because I was consistently hitting my “ten films per month minimum” goal but rarely managing to exceed it (the spikes in April and December being notable exceptions).

I also watched 16 short films. That might not sound like a lot, but it’s actually my third highest total ever, behind only 2019’s 20 and 2020’s 65 (which was so high thanks to watching many for film festivals I was working on), and just ahead of last year’s 15. On the other hand, only 11 were ones I’d never seen before, down marginally from 12 last year. (For some reason I didn’t make that distinction in last year’s stats, but it does affect the total running time, because only the new ones count.)

The total running time of my first-watch features was 229 hours and 3 minutes. That’s my highest since I revamped the site for 2022, but only ninth overall. The same ranking as for the film count? It’s almost as if there’s a correlation! I jest, but what it does suggest is that I rarely, if ever, watch a disproportionate number of especially-short or especially-long films. Talking of short things, add in the (new) short films and that total rises by only just over an hour to 230 hours and 14 minutes. (The additional bit is labelled as “other” on the graph because it would also include any alternate cuts of features that I watched for the first time, but there weren’t any this year. In fact, it’s been five years since there were.)

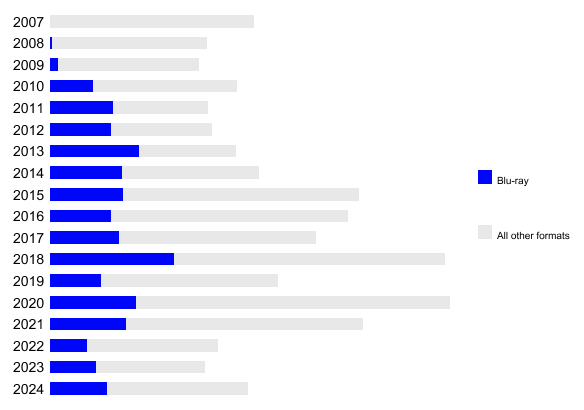

Formats next, and after disappearing last year, TV is back! Okay, it’s only got one film to its name (thanks to the BBC for premiering a new Wallace & Gromit feature on Christmas Day), but it’s something, I guess. Unless there’s another similar must-watch-live event in 2025 (doubtful), I imagine it will drop off again next year.

It will come as no surprise that the year’s most prolific viewing format was digital with 85 films. At 64.9% of my viewing, it’s an increase on last year, though still below the peak of 2020–2022. It was below 50% in 2019, and I’d like to get it back down there in favour of Blu-rays.

“Digital” encompasses a multitude of different platforms and viewing methods, and this year it was downloads that topped them with 20 films (23.5% of digital). Of the streamers, it was actually NOW that emerged victorious for the first time, with 18 films (21.2%), knocking Netflix and Amazon Prime into shared third place with 16 films (18.8%) each. Surging slightly ahead of the “also ran”s, iPlayer accounted for eight films (9.4%), while bringing up the rear were Apple TV+ on three (3.5), Disney+ and MUBI each on two (2.4%), and newcomer Crunchyroll with one (1.2%). Crunchyroll is all about TV and has hardly any films (I think I found a grand total of four), so don’t expect to see them return (although it’s not an impossibility).

Back to the main ranking, Blu-ray did come second with 38 films (29.0%), a raise in number but drop in percentage from last year.

Last year I noted that the addition of a Physical Media category to my Challenge hadn’t actually done much to boost the number of DVDs I watched. This year I took that category away, and DVD did drop slightly, down to six (4.6%); but, considered over a longer timescale, it’s held pretty steady — just look at the graph:

Finally, I made just one trip to the cinema this year (for Dune: Part Two). Other things piqued my interest, but nothing else panned out. Will 2025 fare any better? Well, I’ll be sure to catch the next Mission: Impossible, at least. Hey, one is still better than I managed some years (2013, 2014, and 2022, I’m looking at you).

Looking at formats from a different angle, now. First: in 2024, I watched as many new films in 3D as I did in 2021–2023 combined. Okay, that was still only four, but it’s an improvement. Looking at my Blu-ray collection, I own 63 films in 3D that I’ve never seen (plus about the same again that I’ve seen but not in 3D), so this number should be significantly higher. Maybe I’ll finally boost it up in 2025. (The first number to beat is 2020’s 13. The best ever is 2018’s 18.)

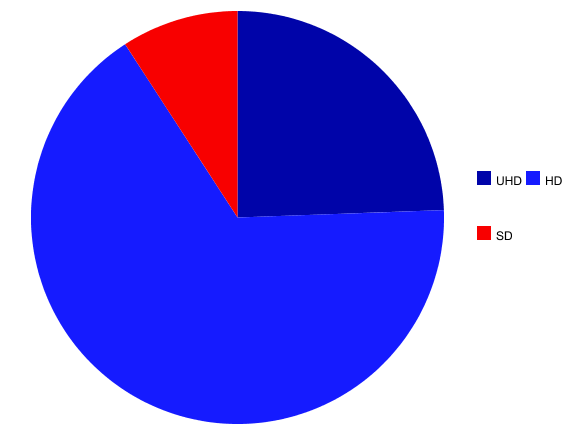

Next, the format du jour, 4K Ultra HD (it still feels pretty new to me, though 4K discs are about to hit their 9th anniversary). I watched 32 films in UHD in 2024, which is a numerical increase from 2023’s 27, but a percentage drop: 24.4% vs last year’s 26.2%. Still, it’s my second best percentage ever, so that’s not nothing. 1080p HD remains the standard, of course, representing a sliver under two-thirds of my viewing at 66.4%. Meanwhile, SD lingers on with 12 films — a hold from last year, but a percentage drop to 9.2%, only the second year it’s been under 10%. Will it ever go away entirely? It would be nice, but there remain plenty of films without even a DVD-quality SD copy out there, never mind all the DVDs that have never received an HD release.

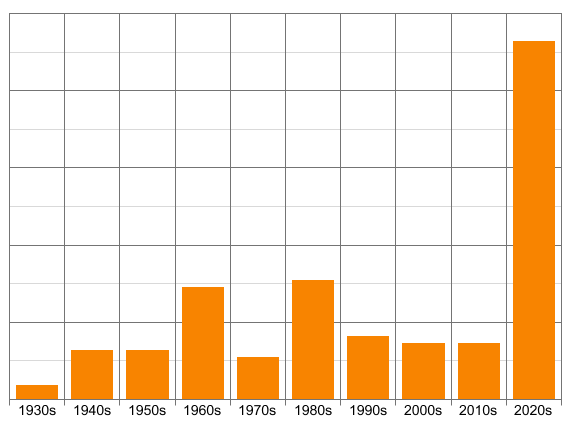

Some people would think that the fact I’m watching so many films in high quality means I’m mostly watching new stuff, but those people are misinformed. Okay, so the the 2020s remains my top decade with 51 films (38.9%), its highest total yet; but other recent decades fare less well, with the 2000s and the 2010s in joint fifth with just eight films (6.1%) each. That’s the third year in a row that my top two decades haven’t been the most recent two; before that, it only happened in 2010 (understandably) and 2019.

The decade that actually landed second place was the 1980s with 17 films (12.98%), closely followed by the ’60s on 16 (12.2%), while the ’90s took fourth with on nine (6.9%). After the first two decades of this century, we come to another tie: the ’40s and the ’50s on seven (5.3%) each. Things are rounded out by the ’70s on six (4.6%) and the ’30s on two (1.5%). No features from before 1932 this year, although I did watch two shorts from the 1920s, five from the 1900s, and even one from the 1890s.

You might think no films from before 1932 would mean no silent films, but there was actually one. At this point I think we’re all aware they still make technically-silent films sometimes, and this year the qualifier was Robot Dreams. I still need to watch more genuine silents from the actual era though, and (minor spoiler alert!) some are almost guaranteed to feature in 2025.

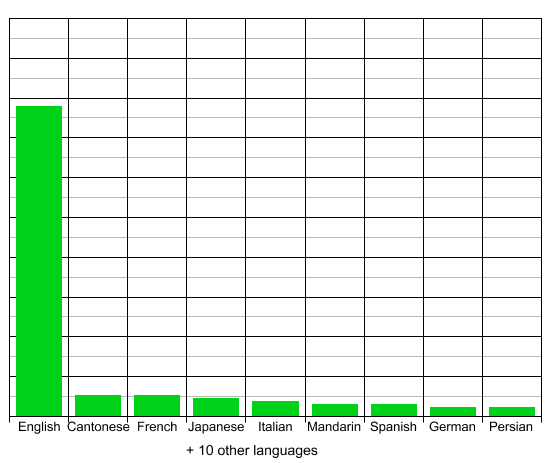

As for spoken languages, English dominated as always, with 102 films wholly or significantly in my mother tongue. At 77.9%, it’s a couple of points up on last year, but still below any previous year. Nonetheless, second place is a distant tie between French and Cantonese in seven films (5.3%) each. They’re closely followed by Japanese in six (4.6%), Italian in five (3.8%), Mandarin and Spanish each in four (3.1%) each, and German and Persian in three (2.3%) apiece. In total, 19 languages were spoken in 2024’s viewing, including Czech and Telugu for the first time on record, and Swedish for the first time since 2020. That tally is better than 2022 or 2023, but still below 2015–2021.

In terms of countries of production, the USA drops below 50% for the first time ever, its 64 films accounting for just 48.85%. Meanwhile, the UK reaches a new percentage high, with 43 films coming out at 32.8%. Lest you think I’m going to brag about being worldly, I’ll note that only 29.0% of films didn’t feature either the US or UK among their listed production countries. Still, there were 31 countries in total in 2024, which is among the better years since I started recording this stat (the highest is 2020’s 40). France were third for the fourth year in a row with 17 films (12.98%), followed by Japan with 11 (8.4%), Hong Kong with nine (6.9%), Italy with eight (6.1%), then a three-way tie between Australia, Canada, and Germany each with five (3.8%).

A total of 114 directors plus eight directing partnerships helmed the feature films I watched in 2024, with a further six directors and four partnerships behind my short film viewing. For the second year in a row, no one was responsible for more than two features, but those with a duo on the list were Abbas Kiarostami, Denis Villeneuve, Joseph Kuo, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Oliver Parker (not to be confused with Ol Parker, who also had one), Robert Tronson, Sammo Hung, W.S. Van Dyke, and Wellson Chin. Plus I watched three shorts credited to British cinema pioneer Cecil Hepworth.

This is my tenth year charting the number of female directors whose work I’ve watched each year. I’d love to say the number and percentage of women-directed films I watch has steadily grown in that time, but it’s actually fluctuated wildly. The low point was 2016, at just 1.66%; the high was 2020, at a still-measly 11.4%; last year, it was 11.2%. In 2024, I watched 10 films with a female director, though two of those were a shared credit (one as part of a duo, one a trio). Counting those shared credits as the appropriate fractions means those 10 films represent 6.74% of my viewing. As terrible as that sounds, it’s still my third best year — so, even worse, then. As I’ve said before, I neither avoid nor especially seek out female directors — arguably I should do more of the latter, but the fact I just watch what I watch and this is how low the percentage is suggests that it’s the industry who really need to do more. That said, as revealed earlier, I watch a relatively high percentage of older films, and you can’t change the past. I hope this graph will improve further in the future, but I doubt it will ever come close to 50/50.

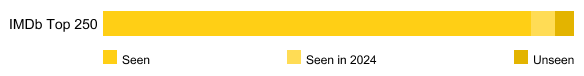

Every year, I track my progress at completing the IMDb Top 250, but this year it’s a bit special because I made it a whole category in my 2024 Challenge. When I made that decision, it wasn’t guaranteed I’d finish the Top 250: the category only required 12 films to complete it and I had a few more than that left on the list. My thinking was: at the very least it will be significant progress; at best, maybe I’d watch a couple more than the prescribed 12 and get the list close to done. Well, I didn’t specifically watch any ‘extra’ films, but titles do come and go (Godzilla Minus One was on the list when I announced my plans in January, but was gone by the time I watched it in September) so maaaybe… but no, I’m still 10 films away from completing it. Goddammit. Comings and goings aside, at the time of writing this article there were 13 films from my 2024 viewing still on the Top 250 — the 12 I watched for the Challenge (listed here) plus Dune: Part Two. Their current positions range from 41st (Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse) to 237th (My Father and My Son). Well, there’s always next year…

As I’m sure you’re aware, at the end of every year I publish a list of 50 notable films I missed from that year’s new releases, which I call my “50 Unseen”. I’ve tracked my progress at watching those ‘misses’ down the years — progress that has been very variable: I didn’t watch too many of them at the start, then went through a period of several years where I made serious inroads, but recently I’ve dropped off again. Put in more practical terms: I hit a high of 68 watched from all previous lists during 2018, but only watched 10 during 2023. There’s a nice bounce in 2024, doubling to 20 films across all 17 lists, although it’s still one of my weaker years (only four were worse). That’s dominated by 12 from 2023’s 50 — a big improvement on the six from 2022 I watched last year, but still my fourth-worst ‘first year’ (historically, I’ve watched the most from any given list in its first year of existence).

In total, I’ve now seen 543 out of 850 ‘missed’ movies. That’s 63.9%, a further drop from last year, though still a little above 2017 (2018 was the first year I got it above 70%). I’d like to get it above 70% again, but to do it by the end of 2025 I’d have to watch 87 films, which is almost double the number I watched in 2022 to 2024 combined. To even hold the percentage steady I’d have to watch 32 films, which is still more than 2023 and 2024 combined, so it’s not looking great. (As usual, 2024’s 50 will be listed in my “best of” post.)

And so we reach the finale of every review; a fitting climax to these statistics: the scores.

For the avoidance of doubt, this stat factors in every new film I watched in 2024, including those I’ve not yet reviewed (this year, that’s 92% of them — an improvement on last year’s 95%, albeit not by much). That does mean there are some where I’m still flexible on my final score; usually films I’ve awarded 3.5 or 4.5 on Letterboxd, but which I insist on rounding to a whole star here. For the sake of completing these stats, I’ve assigned a whole-star rating to every film, but I reserve the right to change my mind when I eventually post a review (it’s happened before). It only applies to a small handful of films, so hopefully this section will remain broadly accurate.

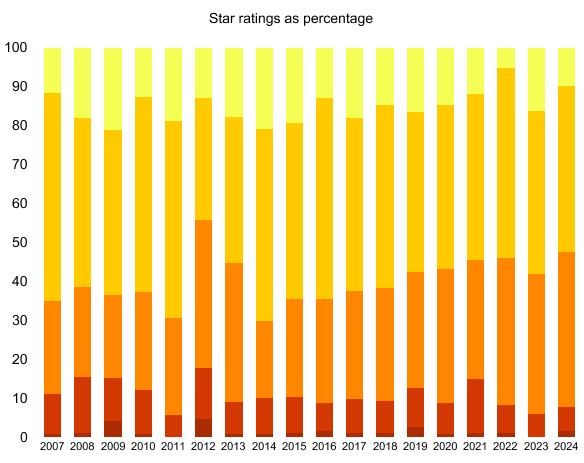

At the top end of the scale, in 2024 I awarded 13 five-star ratings (9.92% of my viewing). That’s down slightly from last year, though not close to as low as 2022. (I’d make comparisons to all other years, but that’s only down fairly as a percentage and I don’t have that to hand. I should compile a list of them, really.) At the scale’s other end, I gave two one-star ratings (1.53%), which is more or less normal for me — indeed, my all-time average is 1.94 per year. Even when I watch more films, it doesn’t change much, because I avoid giving it to all but the most terrible rubbish, and I try to avoid watching such things, on the whole.

The largest group this year was four-stars, given to 56 films (42.75%). Three-stars has only been the majority awarded once (in 2012), but it came pretty close this year, as there were 52 three-star films (39.69%). Finally, there were only eight two-star films (6.11%), which is roughly in-keeping with the last couple of years (before that there were a lot more, but then I watched a lot more in general. I really ought to get those percentages ready for comparison…)

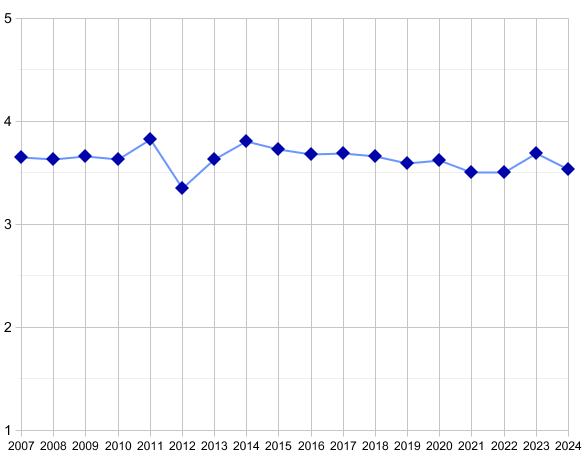

And so to the big final number: the average score for 2024. Oo-ooh! The short version is 3.5 out of 5 — down from last year, but the same as the two years before that. To get more precise (for the sake of comparison, as all of my years fall within a spread of 0.4), at three decimal places the score is 3.534 — that’s above 2021 and 2022, then, but the only other year it bests is 2012 (a real outlier, as you can see on the below chart). As my fourth lowest-scoring year, it’s almost the antithesis to last year, which was fifth highest.

What can we conclude from all that? Nothing much, really. The fact that line is pretty flat (a few oddities aside) suggests both my film choosing and my scoring have remained consistent over the years, for good or ill. Should I choose better films? Should I score more leniently? Or more harshly? To be honest, I don’t really think about such questions. I take these stats as an indication of what’s happened, not as a learning exercise in what I should or shouldn’t change.

Talking of scores and finales, next up is the finale of the 2024 review: my pick of the best from my 131 first-time watches.

The latest series from writer Russell T Davies is a story he’s been mulling for a long time — I seem to remember it first being mentioned in his book The Writer’s Tale, which chronicles his final couple of years on Doctor Who, over a decade ago now. It’s had a bumpy ride to the screen, with the pitch being rejected by several networks, and eventually the planned eight episodes being negotiated down to just five. If this were a lesser writer then you’d assume the concept must have some fundamental flaw(s), but perhaps it was just the subject matter that scared so many commissioners: it’s about the emergence of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, told from the perspective of a gang of mostly-gay twentysomethings who’ll see the disease rip their world to shreds. Not exactly a cheery topic, and one still affected by taboos and ignorance all these decades later. But that’s why this is a story that needed to be told, and here it’s safe in the hands of a master screenwriter.

The latest series from writer Russell T Davies is a story he’s been mulling for a long time — I seem to remember it first being mentioned in his book The Writer’s Tale, which chronicles his final couple of years on Doctor Who, over a decade ago now. It’s had a bumpy ride to the screen, with the pitch being rejected by several networks, and eventually the planned eight episodes being negotiated down to just five. If this were a lesser writer then you’d assume the concept must have some fundamental flaw(s), but perhaps it was just the subject matter that scared so many commissioners: it’s about the emergence of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, told from the perspective of a gang of mostly-gay twentysomethings who’ll see the disease rip their world to shreds. Not exactly a cheery topic, and one still affected by taboos and ignorance all these decades later. But that’s why this is a story that needed to be told, and here it’s safe in the hands of a master screenwriter. WandaVision had seemed to settle itself into a nice little groove in

WandaVision had seemed to settle itself into a nice little groove in  It’s been a very long time since I watched any of The West Wing, and I never saw it in full, but I always meant to go back and watch the whole thing properly. I thought watching this one-off charity reunion thingy might ignite my interest in finally doing that. And, indeed, this did make me want to go back and rectify that — by, ironically, clearly not being as good as the show used to be.

It’s been a very long time since I watched any of The West Wing, and I never saw it in full, but I always meant to go back and watch the whole thing properly. I thought watching this one-off charity reunion thingy might ignite my interest in finally doing that. And, indeed, this did make me want to go back and rectify that — by, ironically, clearly not being as good as the show used to be. That news aside, let’s return our gaze to the 1959–64 iteration of the programme. Having already reviewed many of the best and worst episodes of that original run, I’m now covering episodes that happened to pique my interest. First up this month, What You Need, which jumps straight onto my list of the series’ best episodes. It’s the story of a peddler who can provide people with the one small item that will be of invaluable use to them shortly, and the punter who wants to exploit this power. The episode has a nice balance of sweet whimsy and darkness; the length is perfectly paced for the half-hour; and, although it’s not got one of Twilight Zone‘s famous massive twists, the end is fitting and in-keeping. It’s nicely directed too, particularly the scene where the punter confronts the salesman in his apartment. An excellent episode that deserves to be better regarded.

That news aside, let’s return our gaze to the 1959–64 iteration of the programme. Having already reviewed many of the best and worst episodes of that original run, I’m now covering episodes that happened to pique my interest. First up this month, What You Need, which jumps straight onto my list of the series’ best episodes. It’s the story of a peddler who can provide people with the one small item that will be of invaluable use to them shortly, and the punter who wants to exploit this power. The episode has a nice balance of sweet whimsy and darkness; the length is perfectly paced for the half-hour; and, although it’s not got one of Twilight Zone‘s famous massive twists, the end is fitting and in-keeping. It’s nicely directed too, particularly the scene where the punter confronts the salesman in his apartment. An excellent episode that deserves to be better regarded. Famed sci-fi writer Ray Bradbury’s only formal contribution to the series, I Sing the Body Electric, is another case of a great premise writing cheques the rest of the episode can’t cash. Here, rather than running out of steam, the places it takes us to are morally questionable and raise more questions than they answer. The plot is almost like a sci-fi twist on Mary Poppins: a widowed father is struggling to bring up his three kids, so they get a robot grandma, but one of the daughters doesn’t like her. It’s eventually revealed that the daughter’s distrust stems from the belief that her dead mother “ran away” and she thinks robot-granny will do the same — but it’s okay, because granny’s a robot and can live forever. Hurrah! Maybe your mileage will differ, but the idea that mothers who die have run away from their kids, or that this grief is best handled by giving the kid a parental figure who will never die, all seems a bit distasteful. And that’s before we get to the ending, where we learn that RoboGran’s consciousness will gather with others of her kind so they can share what they’ve learned. It’s spun as if this is somehow a good thing, but to me it sounds like a prequel to

Famed sci-fi writer Ray Bradbury’s only formal contribution to the series, I Sing the Body Electric, is another case of a great premise writing cheques the rest of the episode can’t cash. Here, rather than running out of steam, the places it takes us to are morally questionable and raise more questions than they answer. The plot is almost like a sci-fi twist on Mary Poppins: a widowed father is struggling to bring up his three kids, so they get a robot grandma, but one of the daughters doesn’t like her. It’s eventually revealed that the daughter’s distrust stems from the belief that her dead mother “ran away” and she thinks robot-granny will do the same — but it’s okay, because granny’s a robot and can live forever. Hurrah! Maybe your mileage will differ, but the idea that mothers who die have run away from their kids, or that this grief is best handled by giving the kid a parental figure who will never die, all seems a bit distasteful. And that’s before we get to the ending, where we learn that RoboGran’s consciousness will gather with others of her kind so they can share what they’ve learned. It’s spun as if this is somehow a good thing, but to me it sounds like a prequel to  WandaVision isn’t the first television series set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (in fact, it’s the thirteenth); nor is it the first to feature characters and actors from the movies (that’s been the case in at least two others, off the top of my head); but it is the first to be produced by the same division that makes the movies, so it’s set to be a lot more important (read: not totally ignored) going forward. Indeed, it’s already been reported that the events of this series tie directly into the storylines of

WandaVision isn’t the first television series set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (in fact, it’s the thirteenth); nor is it the first to feature characters and actors from the movies (that’s been the case in at least two others, off the top of my head); but it is the first to be produced by the same division that makes the movies, so it’s set to be a lot more important (read: not totally ignored) going forward. Indeed, it’s already been reported that the events of this series tie directly into the storylines of  The David Tennant- and Michael Sheen-starring (or is that Michael Sheen- and David Tennant-starring?) filmed-over-Zoom sitcom about lockdown life was a hit during one or other of the 2020 lockdowns, so here it is again — just in time for the 2021 lockdown, as things turned out. The second series is very much a follow-up — a sequel, if you will — rather than merely “more episodes of the same”. In fact, it’s a meta-sequel: the first series exists as a fictional project in the world of the sequel. This isn’t a continuation of the storyline(s) we watched in the first series; it’s a follow-on from the fact the first series was a success. Got that? The title card sometimes calls the series Staged², and one feels that’s more than just a typographical play on Staged 2.

The David Tennant- and Michael Sheen-starring (or is that Michael Sheen- and David Tennant-starring?) filmed-over-Zoom sitcom about lockdown life was a hit during one or other of the 2020 lockdowns, so here it is again — just in time for the 2021 lockdown, as things turned out. The second series is very much a follow-up — a sequel, if you will — rather than merely “more episodes of the same”. In fact, it’s a meta-sequel: the first series exists as a fictional project in the world of the sequel. This isn’t a continuation of the storyline(s) we watched in the first series; it’s a follow-on from the fact the first series was a success. Got that? The title card sometimes calls the series Staged², and one feels that’s more than just a typographical play on Staged 2. A trio of new editions of the critic’s explanation of cinematic genres, which play like the best Film Studies lectures you could imagine. Each explores and explains its chosen subject in depth, often spinning out into tangential and related branches of film history — see the episode on pop music movies, for example, which is primarily concerned with movies about pop stars or musicals starring pop stars, but takes a moment to explore the phenomenon of pop stars as proper actors, such as David Bowie’s secondary career. It’s like Kermode and his writers (which include the insanely knowledgeable Kim Newman) can’t help themselves: there’s so much interesting stuff to talk about, so many connections and parallels, and they’re going to squeeze as much of it in as possible. Cited examples are copious and wide-ranging — if an episode is about a subject you’re interested in, be prepared to see your watch list grow. The best of this trilogy is the third, on cult movies; a genre, as Kermode explains, that is defined not by filmmakers but by audiences. It’s also a particularly wide-ranging field, but one whose contents engender genuine love — what makes them cult movies, after all, is that someone loves them. Kermode helps us to understand why.

A trio of new editions of the critic’s explanation of cinematic genres, which play like the best Film Studies lectures you could imagine. Each explores and explains its chosen subject in depth, often spinning out into tangential and related branches of film history — see the episode on pop music movies, for example, which is primarily concerned with movies about pop stars or musicals starring pop stars, but takes a moment to explore the phenomenon of pop stars as proper actors, such as David Bowie’s secondary career. It’s like Kermode and his writers (which include the insanely knowledgeable Kim Newman) can’t help themselves: there’s so much interesting stuff to talk about, so many connections and parallels, and they’re going to squeeze as much of it in as possible. Cited examples are copious and wide-ranging — if an episode is about a subject you’re interested in, be prepared to see your watch list grow. The best of this trilogy is the third, on cult movies; a genre, as Kermode explains, that is defined not by filmmakers but by audiences. It’s also a particularly wide-ranging field, but one whose contents engender genuine love — what makes them cult movies, after all, is that someone loves them. Kermode helps us to understand why. The third season of this Karate Kid TV spinoff/continuation debuted at the start of the month, but I’ve been pacing myself: it’s a really good show and I didn’t want to just burn through it. While I thought season two lacked the moreishness I experienced during

The third season of this Karate Kid TV spinoff/continuation debuted at the start of the month, but I’ve been pacing myself: it’s a really good show and I didn’t want to just burn through it. While I thought season two lacked the moreishness I experienced during  So far on my journey through the original 1959–64 series of The Twilight Zone, I’ve covered ten selections of the best episodes and three of the worst, as chosen by various critics. With 85 episodes still to go, I’m leaving the opinions of others behind (for the time being) to check out some episodes that caught my attention for one reason or another — not because they’re acclaimed as good or derided as bad, but something about the premise grabbed me while I was perusing all those various rankings.

So far on my journey through the original 1959–64 series of The Twilight Zone, I’ve covered ten selections of the best episodes and three of the worst, as chosen by various critics. With 85 episodes still to go, I’m leaving the opinions of others behind (for the time being) to check out some episodes that caught my attention for one reason or another — not because they’re acclaimed as good or derided as bad, but something about the premise grabbed me while I was perusing all those various rankings. An altogether different vision of 1974 is presented in The Old Man in the Cave. This time, it’s a post-apocalyptic world after “the bomb” was dropped, and what’s left of humanity makes do as it can in the remnants of the old world. In particular, one town has survived by following the guidance of an old man who lives in a nearby cave, who seems to know where to plant food, what tinned goods are safe to eat, what the weather will bring, and so on. When a militia turns up (led by James Coburn) planning to bring order to the region, the townsfolk are faced with the choice of continuing to listen to the old man or side with the militia’s view that he’s actually an oppressor and they’re a lot nicer. It turns into a neat little sci-fi fable — the finale says it’s about the error of faithlessness, but I’m more inclined to say it’s about trust in experts vs selfishness and greed. The townsfolk have followed this expert’s guidance for a decade and it’s kept them alive, but that life hasn’t been easy or fun, so they’re tempted by the fantasy sold by the newcomers: that you can have whatever you want; the expert is keeping you down for no reason. Naturally, it can only pan out one way. It’s a story whose moral seems only more pertinent today.

An altogether different vision of 1974 is presented in The Old Man in the Cave. This time, it’s a post-apocalyptic world after “the bomb” was dropped, and what’s left of humanity makes do as it can in the remnants of the old world. In particular, one town has survived by following the guidance of an old man who lives in a nearby cave, who seems to know where to plant food, what tinned goods are safe to eat, what the weather will bring, and so on. When a militia turns up (led by James Coburn) planning to bring order to the region, the townsfolk are faced with the choice of continuing to listen to the old man or side with the militia’s view that he’s actually an oppressor and they’re a lot nicer. It turns into a neat little sci-fi fable — the finale says it’s about the error of faithlessness, but I’m more inclined to say it’s about trust in experts vs selfishness and greed. The townsfolk have followed this expert’s guidance for a decade and it’s kept them alive, but that life hasn’t been easy or fun, so they’re tempted by the fantasy sold by the newcomers: that you can have whatever you want; the expert is keeping you down for no reason. Naturally, it can only pan out one way. It’s a story whose moral seems only more pertinent today. The same could be said of A Kind of a Stopwatch, which takes on a perennial “what if”: what if you could freeze time? It wasn’t an original idea even when this episode was made in 1964, with Serling once saying he received dozens of pitches a year along those lines. He didn’t think any of them had an original enough take on the concept to be worth adapting, until this one. Frankly, I’m not sure what’s so special about it. That’s not to say it’s bad — it’s a reasonably well handled version, although it falls victim to the series’ regular bad habit of having the main character take much longer than the audience to understand the rules of the situation. But the episode’s real flaw comes at the end, when the punishment doesn’t fit the crime: the main character’s fate is not an ironic twist especially suited to him. It’s that which stops Stopwatch from reaching TZ’s true heights; that leaves it a solid “good” episode when it could possibly have been a great one.

The same could be said of A Kind of a Stopwatch, which takes on a perennial “what if”: what if you could freeze time? It wasn’t an original idea even when this episode was made in 1964, with Serling once saying he received dozens of pitches a year along those lines. He didn’t think any of them had an original enough take on the concept to be worth adapting, until this one. Frankly, I’m not sure what’s so special about it. That’s not to say it’s bad — it’s a reasonably well handled version, although it falls victim to the series’ regular bad habit of having the main character take much longer than the audience to understand the rules of the situation. But the episode’s real flaw comes at the end, when the punishment doesn’t fit the crime: the main character’s fate is not an ironic twist especially suited to him. It’s that which stops Stopwatch from reaching TZ’s true heights; that leaves it a solid “good” episode when it could possibly have been a great one. This month, I have mostly been missing It’s a Sin, Russell T Davies’s new drama about a group of friends coming of age amidst the emergence of AIDS in the ’80s. It’s only a couple of episodes in on Channel 4, but the whole five-part series is already available via All 4 (FYI, it’s out in the US on HBO Max in mid-February). I intend to binge the whole thing and review it next month.

This month, I have mostly been missing It’s a Sin, Russell T Davies’s new drama about a group of friends coming of age amidst the emergence of AIDS in the ’80s. It’s only a couple of episodes in on Channel 4, but the whole five-part series is already available via All 4 (FYI, it’s out in the US on HBO Max in mid-February). I intend to binge the whole thing and review it next month. This year’s Doctor Who special felt like a bid by showrunner Chris Chibnall to keep fans happy. Popular character Captain Jack Harkness is back, properly this time — after

This year’s Doctor Who special felt like a bid by showrunner Chris Chibnall to keep fans happy. Popular character Captain Jack Harkness is back, properly this time — after  With theatres mostly shut this November and December due to Covid restrictions, the UK’s traditional pantomime season was a write-off. But where there’s a will there’s a way, and so an all-star bunch of actors and entertainers (including the likes of Olivia Colman, Helena Bonham Carter, Tom Hollander, and Anya Taylor-Joy, plus multiple surprise cameos) came together over Zoom to record this hour-long panto in aid of Comic Relief. (FYI, there are two versions available: a 60-minute one that aired on BBC Two, and

With theatres mostly shut this November and December due to Covid restrictions, the UK’s traditional pantomime season was a write-off. But where there’s a will there’s a way, and so an all-star bunch of actors and entertainers (including the likes of Olivia Colman, Helena Bonham Carter, Tom Hollander, and Anya Taylor-Joy, plus multiple surprise cameos) came together over Zoom to record this hour-long panto in aid of Comic Relief. (FYI, there are two versions available: a 60-minute one that aired on BBC Two, and  Sky’s big special this year was this based-on-a-true-story tale of when a young, bereaved Roald Dahl went on a trip to meet an ageing Beatrix Potter. Two of the great British children’s authors meeting up at very different points in their lives? It’s a wonder no one’s thought to film this before. Although, based on the evidence here, the meeting was fairly short and inconsequential — that they met is an interesting bit of trivia, not a defining moment in either’s life. To get this anecdote up to barely-feature-length (it’s just over an hour without ads), there’s a lot of expanded backstory on both sides. The Roald side feels like it must be broadly true — it’s all about him (and his mother) struggling to cope with the deaths of both his sister and father — but the Beatrix side feels dreamt up to balance it out — it’s just about her arguing with an agent about the contents of her latest book. Eventually, these threads converge on the eponymous pair’s brief meeting… and that’s the end. It’s a slight and gentle film, but it made for moderately charming Christmas Eve fare.

Sky’s big special this year was this based-on-a-true-story tale of when a young, bereaved Roald Dahl went on a trip to meet an ageing Beatrix Potter. Two of the great British children’s authors meeting up at very different points in their lives? It’s a wonder no one’s thought to film this before. Although, based on the evidence here, the meeting was fairly short and inconsequential — that they met is an interesting bit of trivia, not a defining moment in either’s life. To get this anecdote up to barely-feature-length (it’s just over an hour without ads), there’s a lot of expanded backstory on both sides. The Roald side feels like it must be broadly true — it’s all about him (and his mother) struggling to cope with the deaths of both his sister and father — but the Beatrix side feels dreamt up to balance it out — it’s just about her arguing with an agent about the contents of her latest book. Eventually, these threads converge on the eponymous pair’s brief meeting… and that’s the end. It’s a slight and gentle film, but it made for moderately charming Christmas Eve fare. As usual, the schedules were full of sitcoms and panel shows offering half-hour doses of festivals merriment. Highlights included a fourth Christmassy edition of The Goes Wrong Show, in which the accident-prone Cornley Polytechnic Drama Society turned their attention to The Nativity, with predictably disastrous — and hilarious — results. I get that Goes Wrong is too silly for some, but it hits just the right note for me. A more heartwarming tone was struck by the Ghosts special, in which Mike’s overbearing family coming to stay (clearly not set this Christmas, then). In keeping with the style of the recent second series, their presence prompted flashbacks to the life of horny MP Julian, which, via a series of kinky sex parties, delivered a message about appreciating your family while you can.

As usual, the schedules were full of sitcoms and panel shows offering half-hour doses of festivals merriment. Highlights included a fourth Christmassy edition of The Goes Wrong Show, in which the accident-prone Cornley Polytechnic Drama Society turned their attention to The Nativity, with predictably disastrous — and hilarious — results. I get that Goes Wrong is too silly for some, but it hits just the right note for me. A more heartwarming tone was struck by the Ghosts special, in which Mike’s overbearing family coming to stay (clearly not set this Christmas, then). In keeping with the style of the recent second series, their presence prompted flashbacks to the life of horny MP Julian, which, via a series of kinky sex parties, delivered a message about appreciating your family while you can. This Christmas, I have mostly been missing Black Narcissus, the BBC’s three-part re-adaptation of a novel most famous for being adapted into a film by Powell & Pressburger. It’s on iPlayer in UHD now, which is usually an incentive for me to catch it. Talking of three-part re-adaptations, I also didn’t watch Steven Knight’s version of A Christmas Carol — that was on

This Christmas, I have mostly been missing Black Narcissus, the BBC’s three-part re-adaptation of a novel most famous for being adapted into a film by Powell & Pressburger. It’s on iPlayer in UHD now, which is usually an incentive for me to catch it. Talking of three-part re-adaptations, I also didn’t watch Steven Knight’s version of A Christmas Carol — that was on

Favourite Film of the Month

Favourite Film of the Month