2010 #69

Christopher Nolan | 148 mins | cinema | 12A / PG-13

This review ends by calling Inception a “must-see”. I’m telling you this now for two reasons. Primarily, because this review contains major spoilers, and it does seem a little daft to end a review presumably aimed at those who’ve seen the film with a recommendation that they should see it.

This review ends by calling Inception a “must-see”. I’m telling you this now for two reasons. Primarily, because this review contains major spoilers, and it does seem a little daft to end a review presumably aimed at those who’ve seen the film with a recommendation that they should see it.

Secondly, because Inception — and here’s your first spoiler, sort of — also begins at the end. Now, this is normally a sticking point for me: too many films these days do it, the vast majority have no need to. I’m not convinced Inception needs to either, but it makes a better job of it than most. It does mean that, as the film approaches this moment in linear course, you know it’s coming several minutes ahead of its arrival, but for once that may be half the point.

As you undoubtedly know, Inception is about people who can get into dreams and steal ideas. Now they’re employed to get into a dream and plant an idea. This is either impossible or extremely hard, depending on which character you listen to. And that’s the setup — it’s really not as complicated as some would have you imagine. What follows is, in structural terms, a typical heist movie: Leonardo DiCaprio’s Cobb is the leader, he puts together a team of specialists, they do the heist, which has complexities and takes up the third act. Where it gets complicated is that this isn’t a casino robbery or betting scam or whatever other clichés have developed in heist movie history,  but the aforementioned implanting of an idea; and so, the film has to explain to us how this whole business works.

but the aforementioned implanting of an idea; and so, the film has to explain to us how this whole business works.

The explanation of the rules and the intricacies of the plot occupy almost all of Inception’s not-inconsiderable running time. There’s little in the way of character development, there’s (according to some) little in the way of emotion. But do either of these things matter? Or, rather, why do they have to matter? Why can’t a film provide a ‘cold’ logic puzzle for us to deduce, or be shown the methodology of, if that’s what it wants to do? When I watch an emotional drama I don’t complain that there’s no complex series of mysteries for me to unravel; when I settle down to a lightweight comedy I don’t expect insight into human psychology; musical fans don’t watch everything moaning there aren’t enough songs; you don’t watch a chick flick and wonder when the shooting’s going to start. That is, unless you’re being unreasonable with you expectations.

The film centres on Cobb, it uses Ariadne (Ellen Page) as a method to investigate Cobb, and everyone else plays their role in the heist. And that’s fine. Perhaps Ken Watanabe’s Saito could do with some more depth, considering his presence in that opening flashforward and his significance to Cobb’s future, but then perhaps he’s the one who most benefits from the mystery. Some would like Michael Caine’s or Pete Postlethwaite’s characters to have more development and, bluntly, screentime; but I think their little-more-than-cameos do a lovely job of wrongfooting you, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Some say the same thing about Lukas Haas’ tiny role, but I don’t know who he is so he may as well be anyone to me. Cast aside, there’s not much humour — well, no one promised you a comedy. At best you could claim it should be a wise-cracking old-school actioner, but it didn’t promise that either.

could do with some more depth, considering his presence in that opening flashforward and his significance to Cobb’s future, but then perhaps he’s the one who most benefits from the mystery. Some would like Michael Caine’s or Pete Postlethwaite’s characters to have more development and, bluntly, screentime; but I think their little-more-than-cameos do a lovely job of wrongfooting you, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Some say the same thing about Lukas Haas’ tiny role, but I don’t know who he is so he may as well be anyone to me. Cast aside, there’s not much humour — well, no one promised you a comedy. At best you could claim it should be a wise-cracking old-school actioner, but it didn’t promise that either.

To complain about these things being missing is, in my view, to prejudge the film; to look at it thinking, “this is potentially the greatest film ever because, well, I would quite like it to be. And so it must have a bit of everything I’ve ever liked in a film”. Which is patently rubbish.

Taken on its own merits, Inception presents itself as a heist movie, a big puzzle to be solved, with a team leader who has some of his own demons. Now, you can argue that his demons are revealed in chunks of exposition rather than genuine emotion, and that might be a valid criticism that I wouldn’t necessarily disagree with; and you can argue that we’re not shown enough of the planning to fully appreciate the big damn logic puzzle of the heist, instead just seeing it unfold too quickly as they rush deeper and deeper into levels of dream, and I wouldn’t necessarily disagree with that either; and you can argue that some of the action sequences could benefit from the narrative clarity Nolan (in both writer and director hats) clearly has about which level’s which and how they impact on each other, and I wouldn’t necessarily disagree with that either… but if you’re going to expect the film to offer something it didn’t suggest it was going to… well, tough.

And the film isn’t entirely devoid of character, it’s just light on it. All the performances are fine. DiCaprio is finally beginning to look older than 18 and better able to convince as a man who has lost his family and therefore most of what he cares about.  He wants a way home, he gets a shot at it, and he goes for it. Him aside, it’s a bit hard to call on the performances after one viewing: there’s nothing wrong with any of them, it’s just that they’ve not got a great deal to do — the film is, as noted, more concerned with explaining the world and the heist. How much anyone has put into their part might only become apparent (at least to this reviewer) on repeated viewings. Probably the most memorable, however, is Tom Hardy’s Eames, which is at least in part because he gets the lion’s share of both charm and funny lines.

He wants a way home, he gets a shot at it, and he goes for it. Him aside, it’s a bit hard to call on the performances after one viewing: there’s nothing wrong with any of them, it’s just that they’ve not got a great deal to do — the film is, as noted, more concerned with explaining the world and the heist. How much anyone has put into their part might only become apparent (at least to this reviewer) on repeated viewings. Probably the most memorable, however, is Tom Hardy’s Eames, which is at least in part because he gets the lion’s share of both charm and funny lines.

The plot and technicalities of the world are mostly well explained. Is it dense? Yes. Some have confused this for a lack of clarity but, aside from a few flaws I’ll raise in a minute, everything you need is there. Some, even those who liked it, have criticised it for the bits it definitely does leave out. How exactly can Saito get Cobb home? Whose subconscious are they going into now? What are the full details of the way the machinery they use works? The thing is, it doesn’t matter. None of it does. It would’ve taken Nolan ten seconds to explain some of these things, but does he need to? No. Do you really care? OK, well — Saito is best chums with the US Attorney General, so he asks nicely and Cobb’s off the hook. Sorted. It’s not in the film because it doesn’t need to be; it’s not actually relevant to the story, or the themes, or the characters, or anything else.  Apparently this distracts some people. Well, I can’t tell them it’s fine if it’s going to keep distracting them, but…

Apparently this distracts some people. Well, I can’t tell them it’s fine if it’s going to keep distracting them, but…

It’s fine. Because Nolan only skips over information we don’t need to know — precisely because we don’t need it. Should it matter whose mind we’re in? Maybe it should. But it would seem it doesn’t, because it’s all constructed by Ariadne and populated by the target anyway, and apparently anyone’s thoughts can interfere — they never go into Cobb’s mind, but Mal is always cropping up, not to mention that freight train — so why do we care whose brain they’re in? It seems little more than a technicality. And as for how the system works… well, we’re given hints at how it developed, and the rules and other variables are explained (for example, how mixing different chemicals affects the level of sleep and, as it turns out, whether you get to wake up), but — again — we’re told everything we need to know and no more. Because you don’t need anything else. It’s all covered. And if it’s as complicated as so many are saying, why are you begging for unnecessary detail?

And I have more issues with other reviews, actually. I think the desire for more outlandish dreams is misplaced. It’s clearly explained that the dreamer can’t be allowed to know he’s dreaming, so surely if they were in some trippy psychedelic dreamscape — which would hardly be original either, to boot — they’d probably catch on this wasn’t Reality.  On the flip side, this rule could be easily worked around — “in dreams, we just accept everything that happens as possible, even when it obviously isn’t” — but where’s the dramatic tension in that? There’s tension in them needing to be convinced it’s real; if anything goes… well, anything goes, nothing would be of consequence, the only story would be them completing a danger-free walk-in-the-park mission.

On the flip side, this rule could be easily worked around — “in dreams, we just accept everything that happens as possible, even when it obviously isn’t” — but where’s the dramatic tension in that? There’s tension in them needing to be convinced it’s real; if anything goes… well, anything goes, nothing would be of consequence, the only story would be them completing a danger-free walk-in-the-park mission.

Much has also been made in reviews of the skill displayed by editor Lee Smith in cutting back & forth between the multiple dream levels, a supposedly incredibly hard job. And it is well done, make no mistake — but it also sounds harder than it is. Really, it’s little different than keeping track of characters in three or four different locations simultaneously; it’s just that these locations are levels of dream/consciousness rather than worldly space. Still no mean feat, but not as hard as keeping three different time periods/narrators distinct and clear, as Nolan & co did in The Prestige.

Then there’s the final shot, which has initiated mass debating in some corners of the internet (yes, that dire pun is fully intentional). In my estimation, and despite some people’s claims to definitiveness, it proves nothing. Some have taken it as undoubted confirmation that Cobb is dreaming all along — the top keeps spinning! Mal said it never stops in a dream! — but I swear we saw it stop earlier in the film, so was that not a dream but now he is in one? How would that work? Others have suggested Cobb is in fact the victim of an inception; that we’ve watched a con movie where we never saw the team, and couldn’t work out who they were. Perhaps; but for this to work surely it’s dependent on a way that we can work out who they were, and what their plan was, and how they did it? Otherwise we may as well start picking on every movie and say “ah, but characters X, Y and Z are actually a secret team doing a secret thing, but we never know what the secret thing is, or what the result of that is”. In other words, it’s pointless unless it’s decipherable.

“ah, but characters X, Y and Z are actually a secret team doing a secret thing, but we never know what the secret thing is, or what the result of that is”. In other words, it’s pointless unless it’s decipherable.

And still further, the top doesn’t stop spinning on screen. But you can make those things spin for a damn long time before they fall over, if you do it right, so who can say it’s just not done yet? If it does fall over, eventually, sometime after the credits end, then that’s that, it’s the real world after all. Presumably. And that’s without starting on all the other evidence throughout the film: repeated phrases, unclear jumps in location, the first scene that may or may not be different the second time we see it…

Something’s going on, but is it just thematic, or is it all meant to hint that Cobb’s in a dream? And if he is, who (if anyone) is controlling it? To what end? I’m certain that those answers, at least, aren’t to be found, so, again, are the questions valid? My view — on the final shot, at least — is, perhaps too pragmatically, that it’s just a parting shot from Nolan: it doesn’t reveal the Secret Truth of the whole film, it just suggests that maybe — maybe — there’s even more going on. Maybe. And I’m not sure he even knows what that would be or if there is;  beyond that the top still spinning as the credits roll is an obvious, irresistible tease. He wouldn’t be the first filmmaker to do such a thing Just Because.

beyond that the top still spinning as the credits roll is an obvious, irresistible tease. He wouldn’t be the first filmmaker to do such a thing Just Because.

Or there’s always the ‘third version’: that the top doesn’t stop not because it doesn’t stop but because the film ends. Ooh, film-school-tastic. Also, stating the bleeding obvious. I believe it was suggested as a bona fide explanation by one of Lost’s producers, and so is surely automatically classifiable in the “tosh” bin along with that TV series. Presumably it’s ‘deep thoughts’ like that which led to an ending that left many fans unsatisfied. But I digress. He’s right in the sense that the film doesn’t tell us, but it’s not an explanation of it in and of itself unless you want to be insufferably pretentious: it is ambiguous, yes, but it’s not a comment on the artificiality of storytelling or whatever. And if it is… well, I’ll choose to ignore that, thanks, because, no.

I alluded earlier to flaws. If anything, the final act heist is too quick. With, ultimately, four layers of dreams to progress through, not enough time is devoted to establishing and utilising each one. It’s as if Nolan set up a neat idea then realised he couldn’t fully exploit it. They have a week in one world, months in the next, years in the next… but it doesn’t matter, because events come into play that give them increasingly less time at each level. Would it not have been more interesting to craft a heist that actually used the years of dreamtime at their disposal, rather than a fast-edited & scored extended  action sequence across all four levels? It makes for an exciting finale when they need to get out, true, but I couldn’t help feeling it didn’t exploit one of the more memorable and significant elements enough.

action sequence across all four levels? It makes for an exciting finale when they need to get out, true, but I couldn’t help feeling it didn’t exploit one of the more memorable and significant elements enough.

Indeed, at times the film operates with such efficiency that one can’t help but wonder if there’s another half-hour cut out that it would be quite nice to have back. I appreciate some have criticised the film for already being too long; it would seem I quite decidedly disagree. And not in the fannish “oh I just want more” way that really means they should just get hold of a copy and watch it on loop; I literally mean it could be around half an hour longer and, assuming that half-hour was filling the bits I felt could handle some filling (i.e. not the omitted bits I was fine with nine paragraphs back), I would be more than happy with that. I did not get bored once.

Still on the flaws: Mal (that’d be Cobb’s wife — I’ve been assuming you knew this, sorry if I shouldn’t have) is talked up as a great, interfering, troublesome force…  yet she’s rarely that much of a bother. At the start, sure, so we know that she is; and then in Cobb’s own mind when Ariadne pops in for a visit, but that’s why he’s there so it goes without saying; and then, really, it’s not ’til she puts in a brief appearance to execute Fischer that we see her again (unless I’m forgetting a moment?) And apparently Ariadne has had some great realisation that Mal’s affecting Cobb’s work, and Ariadne’s the only one who knows this… but hold on, didn’t Arthur seem all too aware of how often Mal had been cropping up? Does he promptly forget this after she shoots him? Mal is a potentially interesting villainess, especially as she’s actually a construct of Cobb’s subconscious, but I’m not convinced her part is fully developed in the middle.

yet she’s rarely that much of a bother. At the start, sure, so we know that she is; and then in Cobb’s own mind when Ariadne pops in for a visit, but that’s why he’s there so it goes without saying; and then, really, it’s not ’til she puts in a brief appearance to execute Fischer that we see her again (unless I’m forgetting a moment?) And apparently Ariadne has had some great realisation that Mal’s affecting Cobb’s work, and Ariadne’s the only one who knows this… but hold on, didn’t Arthur seem all too aware of how often Mal had been cropping up? Does he promptly forget this after she shoots him? Mal is a potentially interesting villainess, especially as she’s actually a construct of Cobb’s subconscious, but I’m not convinced her part is fully developed in the middle.

On a different note, some of the visuals are truly spectacular. I don’t hold to the notion, expressed by some disappointed reviewers, that we’ve seen it all before. The Matrix may have offered broadly similar basic concepts in places, but Inception provides enough work of its own for that not to matter. But there is another problem: we have seen it all before. In the trailer. It’s a little like (oddly) Wanted. That comic book adaptation promised amazing, outrageous, impossible stunts through an array showcased in the trailer. “Wow,” thought (some) viewers, “if that’s what’s in the trailer, imagine what they’ve saved for the film!” Turned out, nothing. And Inception is pretty much the same. The exploding Parisian street, the folding city, the  zero-G corridor, the crumbling cliff-faces… all look great, but there’s barely any astounding visual that wasn’t shown in full in the trailer. Is that a problem? Only fleetingly.

zero-G corridor, the crumbling cliff-faces… all look great, but there’s barely any astounding visual that wasn’t shown in full in the trailer. Is that a problem? Only fleetingly.

But it’s the kind of thing that makes me think Inception will work better on a second viewing. Not for the sake of understanding, but to remove it from the hype and expectation. I’ve seen it now, I know what it is, I’ve seen what it has to offer, I’ve had the glowing reviews and the lambasting reviews either affirmed or rejected, and next time I can actually get a handle on what the film is like. Which makes for an anti-climactic ending to a review, really — “ah, I’ll tell you next time”. Well, I can say this:

Inception is certainly worth watching. I’m not sure it’s a masterpiece — maybe it is — but I’m certain it’s not bad. I don’t think it’s as complicated to follow as some believe, but maybe that’s just because I was prepared to pay attention, and equally prepared to disregard the bits that aren’t necessary rather than struggle to fully comprehend every minute detail. It is flawed, though perhaps some of those I picked up on can be explained (in the way I’m certain some others I’ve discussed can be explained).  Is it cold and unemotional? Not entirely. Is it more concerned with the technicalities of the heist and the rules of the game than its characters and their emotions? Yes. Is that a problem? Not really.

Is it cold and unemotional? Not entirely. Is it more concerned with the technicalities of the heist and the rules of the game than its characters and their emotions? Yes. Is that a problem? Not really.

At the very least, if only for all the reaction it’s provoked and the debate it will continue to foster, Inception qualifies as a must-see.

Inception placed 3rd on my list of The Ten Best Films I Saw For the First Time in 2010, which can be read in full here.

2016 Academy Awards

2016 Academy Awards The Revenant is the

The Revenant is the  In some respects it’s a shame the rest of the cast were consequently overshadowed — Leo may spend a huge chunk of the film on his own, but there are frequent cutaways to what everyone else is up to. Tom Hardy is the obvious standout as selfish bastard Fitzgerald, a perfectly detestable but completely believable villain — I’m not saying we’d all sink to his depths, but I’m not convinced most of us are above some of the choices he makes, either. Will Poulter steps outside the comedy roles he’s mostly taken since his

In some respects it’s a shame the rest of the cast were consequently overshadowed — Leo may spend a huge chunk of the film on his own, but there are frequent cutaways to what everyone else is up to. Tom Hardy is the obvious standout as selfish bastard Fitzgerald, a perfectly detestable but completely believable villain — I’m not saying we’d all sink to his depths, but I’m not convinced most of us are above some of the choices he makes, either. Will Poulter steps outside the comedy roles he’s mostly taken since his  The avoidance of pat depictions extends to its portrayal of Native Americans, too. They’re neither simplistic Evil Foreigners, nor a “we’re so sorry for how we’ve treated them before, they’re great really” apologia. Instead, they’re just as brutal and as human as the rest of us, and made up of varied groups who behave differently, or even slaughter among themselves. The main band of Indians we see do serve as the film’s villains (as if Fitzgerald wasn’t bad enough), a hunting party acting out an inverted

The avoidance of pat depictions extends to its portrayal of Native Americans, too. They’re neither simplistic Evil Foreigners, nor a “we’re so sorry for how we’ve treated them before, they’re great really” apologia. Instead, they’re just as brutal and as human as the rest of us, and made up of varied groups who behave differently, or even slaughter among themselves. The main band of Indians we see do serve as the film’s villains (as if Fitzgerald wasn’t bad enough), a hunting party acting out an inverted  At the Oscars, I was pulling for Roger Deakins to make it 13th time lucky, or for

At the Oscars, I was pulling for Roger Deakins to make it 13th time lucky, or for  but focus on the first and last acts and it absolutely is.

but focus on the first and last acts and it absolutely is. Two estranged brothers (Tom Hardy and Joel Edgerton), who’ve taken very different paths in life to escape their alcoholic and abusive father (Nick Nolte), wind up entering the mixed martial arts tournament to end all mixed martial arts tournaments, their eyes on the unprecedentedly massive cash prize — one to save his house and family, the other to help the widow of his Army chum. As they separately go up against an array of more experienced opponents, who could possibly end up in the final bout? Hm, I wonder…

Two estranged brothers (Tom Hardy and Joel Edgerton), who’ve taken very different paths in life to escape their alcoholic and abusive father (Nick Nolte), wind up entering the mixed martial arts tournament to end all mixed martial arts tournaments, their eyes on the unprecedentedly massive cash prize — one to save his house and family, the other to help the widow of his Army chum. As they separately go up against an array of more experienced opponents, who could possibly end up in the final bout? Hm, I wonder… I think they’re being a bit harsh but I can see where they’re coming from. Now, I’m almost loath to give it 4 because I don’t agree with the consensus. And it’s a particularly strange consensus: everyone seems to acknowledge it’s terribly clichéd, but then give it a pass on that. Why? Why don’t you show the same leniency to the tonnes of other movies you rip to shreds for their clichés?

I think they’re being a bit harsh but I can see where they’re coming from. Now, I’m almost loath to give it 4 because I don’t agree with the consensus. And it’s a particularly strange consensus: everyone seems to acknowledge it’s terribly clichéd, but then give it a pass on that. Why? Why don’t you show the same leniency to the tonnes of other movies you rip to shreds for their clichés? though I’m not sure his character arc actually reaches any kind of ending. The rest of the cast are adequate: Joel Edgerton is decent as an upstanding family man; Jennifer Morrison has little to do as his wife; Frank Grillo is convincing as a trainer who bases his philosophy on classical music; Kevin Dunn gets some amusing moments as Edgerton’s school principal. Other people sometimes say words.

though I’m not sure his character arc actually reaches any kind of ending. The rest of the cast are adequate: Joel Edgerton is decent as an upstanding family man; Jennifer Morrison has little to do as his wife; Frank Grillo is convincing as a trainer who bases his philosophy on classical music; Kevin Dunn gets some amusing moments as Edgerton’s school principal. Other people sometimes say words.

“Tom Hardy goes for a drive and makes some phone calls” is the plot of this film, which is often mislabelled as a thriller. That’s not to degrade its thrillingness, but rather to say that if you’re expecting a single-location single-character phone-based thrill-ride like

“Tom Hardy goes for a drive and makes some phone calls” is the plot of this film, which is often mislabelled as a thriller. That’s not to degrade its thrillingness, but rather to say that if you’re expecting a single-location single-character phone-based thrill-ride like  and in the process turning his life upside down. Another part was to tell a story about an ordinary guy dealing with events that aren’t going to change the world, aren’t even going to make the papers, but are a big deal in his life. Something like this could happen to any of us, and how would we deal with it?

and in the process turning his life upside down. Another part was to tell a story about an ordinary guy dealing with events that aren’t going to change the world, aren’t even going to make the papers, but are a big deal in his life. Something like this could happen to any of us, and how would we deal with it? The rest of the cast appear as voices only on the other end of the phone, and in their own way are quite starry — faces that you may recognise, mainly from British TV, in even some of the smaller roles. Not that you see their faces, so, you know, you might have to look them up, or watch the making-of. Some of the performances err a little towards radio acting for me, which is kind of understandable seeing as how that’s basically how they were recorded, but there are particularly good turns from Andrew “Moriarty in

The rest of the cast appear as voices only on the other end of the phone, and in their own way are quite starry — faces that you may recognise, mainly from British TV, in even some of the smaller roles. Not that you see their faces, so, you know, you might have to look them up, or watch the making-of. Some of the performances err a little towards radio acting for me, which is kind of understandable seeing as how that’s basically how they were recorded, but there are particularly good turns from Andrew “Moriarty in  this is about what’s happening on Hardy’s face, not with his whole body. And in either form you’d lose all the photography of nighttime motorways, which have their own kind of hazy beauty. For a movie about someone making phone calls, it is intensely cinematic.

this is about what’s happening on Hardy’s face, not with his whole body. And in either form you’d lose all the photography of nighttime motorways, which have their own kind of hazy beauty. For a movie about someone making phone calls, it is intensely cinematic. the supporting cast are so much more than “voices on the phone” (listen out, too, for Tom “

the supporting cast are so much more than “voices on the phone” (listen out, too, for Tom “ After a decades-long diversion into children’s movies like

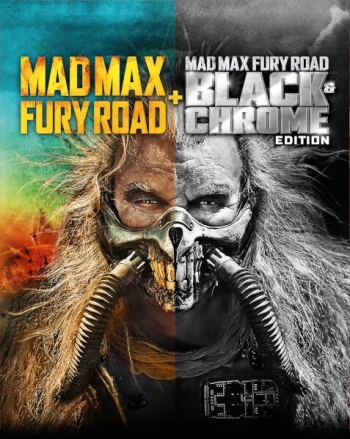

After a decades-long diversion into children’s movies like  I say that, but the finished film is visually stunning on two levels: cinematography and editing. It was shot by John Seale, and Miller had him amp up the saturation. The point was to do the opposite of most post-apocalyptic blockbusters, which are normally desaturated to heck, and it indeed creates something strikingly different. Conversely, Miller has intimated the ideal version of the movie is in black and white with no dialogue, just the score — completely visually-focused storytelling. I have a feeling he’s right, or that it would at least work well. Some nuance would be lost, but all the major plot points and character arcs would be followable.

I say that, but the finished film is visually stunning on two levels: cinematography and editing. It was shot by John Seale, and Miller had him amp up the saturation. The point was to do the opposite of most post-apocalyptic blockbusters, which are normally desaturated to heck, and it indeed creates something strikingly different. Conversely, Miller has intimated the ideal version of the movie is in black and white with no dialogue, just the score — completely visually-focused storytelling. I have a feeling he’s right, or that it would at least work well. Some nuance would be lost, but all the major plot points and character arcs would be followable. but all are deftly executed. That it doesn’t expound on these at length, or linger on their detail, means you have to pay attention to get the most out of that side of the film. I guess some would counter that with, “you have to look hard because you’re reading something that isn’t there,” but I refute that. That it doesn’t spell everything out at length, or hammer home its points and themes heavy-handedly, is a good thing.

but all are deftly executed. That it doesn’t expound on these at length, or linger on their detail, means you have to pay attention to get the most out of that side of the film. I guess some would counter that with, “you have to look hard because you’re reading something that isn’t there,” but I refute that. That it doesn’t spell everything out at length, or hammer home its points and themes heavy-handedly, is a good thing. (Ooh, that turned a bit philosophical, didn’t it?)

(Ooh, that turned a bit philosophical, didn’t it?) After the widespread disappointment with

After the widespread disappointment with  though the knowledge of better things to come means his presence somehow lifts his scenes a notch.

though the knowledge of better things to come means his presence somehow lifts his scenes a notch.

This review ends by calling Inception a “must-see”. I’m telling you this now for two reasons. Primarily, because this review contains major spoilers, and it does seem a little daft to end a review presumably aimed at those who’ve seen the film with a recommendation that they should see it.

This review ends by calling Inception a “must-see”. I’m telling you this now for two reasons. Primarily, because this review contains major spoilers, and it does seem a little daft to end a review presumably aimed at those who’ve seen the film with a recommendation that they should see it. but the aforementioned implanting of an idea; and so, the film has to explain to us how this whole business works.

but the aforementioned implanting of an idea; and so, the film has to explain to us how this whole business works. could do with some more depth, considering his presence in that opening flashforward and his significance to Cobb’s future, but then perhaps he’s the one who most benefits from the mystery. Some would like Michael Caine’s or Pete Postlethwaite’s characters to have more development and, bluntly, screentime; but I think their little-more-than-cameos do a lovely job of wrongfooting you, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Some say the same thing about Lukas Haas’ tiny role, but I don’t know who he is so he may as well be anyone to me. Cast aside, there’s not much humour — well, no one promised you a comedy. At best you could claim it should be a wise-cracking old-school actioner, but it didn’t promise that either.

could do with some more depth, considering his presence in that opening flashforward and his significance to Cobb’s future, but then perhaps he’s the one who most benefits from the mystery. Some would like Michael Caine’s or Pete Postlethwaite’s characters to have more development and, bluntly, screentime; but I think their little-more-than-cameos do a lovely job of wrongfooting you, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Some say the same thing about Lukas Haas’ tiny role, but I don’t know who he is so he may as well be anyone to me. Cast aside, there’s not much humour — well, no one promised you a comedy. At best you could claim it should be a wise-cracking old-school actioner, but it didn’t promise that either.

He wants a way home, he gets a shot at it, and he goes for it. Him aside, it’s a bit hard to call on the performances after one viewing: there’s nothing wrong with any of them, it’s just that they’ve not got a great deal to do — the film is, as noted, more concerned with explaining the world and the heist. How much anyone has put into their part might only become apparent (at least to this reviewer) on repeated viewings. Probably the most memorable, however, is Tom Hardy’s Eames, which is at least in part because he gets the lion’s share of both charm and funny lines.

He wants a way home, he gets a shot at it, and he goes for it. Him aside, it’s a bit hard to call on the performances after one viewing: there’s nothing wrong with any of them, it’s just that they’ve not got a great deal to do — the film is, as noted, more concerned with explaining the world and the heist. How much anyone has put into their part might only become apparent (at least to this reviewer) on repeated viewings. Probably the most memorable, however, is Tom Hardy’s Eames, which is at least in part because he gets the lion’s share of both charm and funny lines. Apparently this distracts some people. Well, I can’t tell them it’s fine if it’s going to keep distracting them, but…

Apparently this distracts some people. Well, I can’t tell them it’s fine if it’s going to keep distracting them, but… On the flip side, this rule could be easily worked around — “in dreams, we just accept everything that happens as possible, even when it obviously isn’t” — but where’s the dramatic tension in that? There’s tension in them needing to be convinced it’s real; if anything goes… well, anything goes, nothing would be of consequence, the only story would be them completing a danger-free walk-in-the-park mission.

On the flip side, this rule could be easily worked around — “in dreams, we just accept everything that happens as possible, even when it obviously isn’t” — but where’s the dramatic tension in that? There’s tension in them needing to be convinced it’s real; if anything goes… well, anything goes, nothing would be of consequence, the only story would be them completing a danger-free walk-in-the-park mission.

“ah, but characters X, Y and Z are actually a secret team doing a secret thing, but we never know what the secret thing is, or what the result of that is”. In other words, it’s pointless unless it’s decipherable.

“ah, but characters X, Y and Z are actually a secret team doing a secret thing, but we never know what the secret thing is, or what the result of that is”. In other words, it’s pointless unless it’s decipherable. beyond that the top still spinning as the credits roll is an obvious, irresistible tease. He wouldn’t be the first filmmaker to do such a thing Just Because.

beyond that the top still spinning as the credits roll is an obvious, irresistible tease. He wouldn’t be the first filmmaker to do such a thing Just Because.

action sequence across all four levels? It makes for an exciting finale when they need to get out, true, but I couldn’t help feeling it didn’t exploit one of the more memorable and significant elements enough.

action sequence across all four levels? It makes for an exciting finale when they need to get out, true, but I couldn’t help feeling it didn’t exploit one of the more memorable and significant elements enough. yet she’s rarely that much of a bother. At the start, sure, so we know that she is; and then in Cobb’s own mind when Ariadne pops in for a visit, but that’s why he’s there so it goes without saying; and then, really, it’s not ’til she puts in a brief appearance to execute Fischer that we see her again (unless I’m forgetting a moment?) And apparently Ariadne has had some great realisation that Mal’s affecting Cobb’s work, and Ariadne’s the only one who knows this… but hold on, didn’t Arthur seem all too aware of how often Mal had been cropping up? Does he promptly forget this after she shoots him? Mal is a potentially interesting villainess, especially as she’s actually a construct of Cobb’s subconscious, but I’m not convinced her part is fully developed in the middle.

yet she’s rarely that much of a bother. At the start, sure, so we know that she is; and then in Cobb’s own mind when Ariadne pops in for a visit, but that’s why he’s there so it goes without saying; and then, really, it’s not ’til she puts in a brief appearance to execute Fischer that we see her again (unless I’m forgetting a moment?) And apparently Ariadne has had some great realisation that Mal’s affecting Cobb’s work, and Ariadne’s the only one who knows this… but hold on, didn’t Arthur seem all too aware of how often Mal had been cropping up? Does he promptly forget this after she shoots him? Mal is a potentially interesting villainess, especially as she’s actually a construct of Cobb’s subconscious, but I’m not convinced her part is fully developed in the middle. zero-G corridor, the crumbling cliff-faces… all look great, but there’s barely any astounding visual that wasn’t shown in full in the trailer. Is that a problem? Only fleetingly.

zero-G corridor, the crumbling cliff-faces… all look great, but there’s barely any astounding visual that wasn’t shown in full in the trailer. Is that a problem? Only fleetingly. Is it cold and unemotional? Not entirely. Is it more concerned with the technicalities of the heist and the rules of the game than its characters and their emotions? Yes. Is that a problem? Not really.

Is it cold and unemotional? Not entirely. Is it more concerned with the technicalities of the heist and the rules of the game than its characters and their emotions? Yes. Is that a problem? Not really.