Each of these films was nominated for multiple Oscars… but failed to win a single one.

In today’s roundup:

(1988)

Big is one of those strange gaps in my viewing — the kind of film I feel I should’ve seen when I was a kid in the early ’90s but didn’t.

Anyway, in case you’ve forgotten, it’s the one where a 12-year-old boy makes a wish and ends up as an adult, played by Tom Hanks. Rather than solve this problem in a day or two, he ends up moving to the city, getting a job, an apartment, a relationship, and all that grown-up stuff. Maybe it’s just me, but I didn’t expect that level of scale from a movie like this. Generally there’s some hijinks around “kid in an adult’s body” and it’s all solved in a day or two, but the length of time the kid’s predicament rolls on for allows the movie to tap into more than that. I mean, it’s still a funny movie, but it’s got a message about how it’s important to remember the childlike spirit, but also that it’s OK to be at whatever stage in life you’re at — don’t rush it.

Plus the whole thing has a kind of sweet innocence that you rarely see in movies nowadays. We’re all too cynical, too concerned with realism (even in fantasy movies). If you made it today, it’d ether have to be sexed/toughened up for a PG-13, or kiddified (and likely animated) for a G. That said, that the 12-year-old boy in a man’s body is happy to sleep with the hot woman, apparently without it bothering his conscience one iota, is by far the most realistic thing about this movie.

* The UK PG version is cut by two seconds to remove an F word. The cut is really obvious, too — was there not a TV version with an ADR’d non-swear? Anyway, it was classified uncut as a 12 in 2008, though that’s not the version they show on TV, clearly. ^

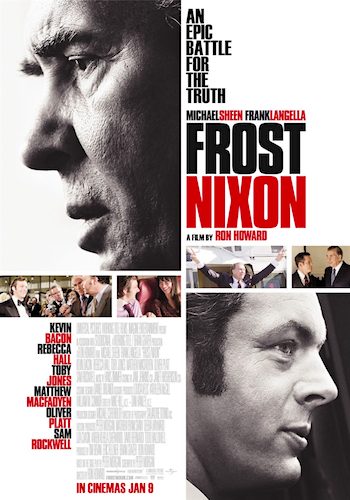

(2008)

Ron Howard | 117 mins | DVD | 2.35:1 | USA, UK & France / English | 15 / R

Peter Morgan’s acclaimed play about the famous interviews between David Frost and President Richard Nixon (the ones where he said “when the President does it, that means it’s not illegal”) transfers to the big screen with its two lead cast members intact (Michael Sheen as Frost and Frank Langella as Nixon) and Ron Howard at the helm.

As a film, it almost embodies every pro and con that’s ever been aimed at Howard’s directing: it’s classy and thoughtful, in the way you’d expect from a director who’s helmed eleven Oscar-nominated movies* and won two himself; but it also, for example, employs an odd framing device of having the supporting cast be interviewed as if for a documentary, which exists solely as an on-the-nose way of integrating direct-to-audience narration from the original play — my point being, it’s a bit straightforward and workmanlike.

Still, when you’ve got actors of the calibre of Sheen and Langella giving first-rate performances (the latter got an Oscar nomination, the former didn’t, I reckon only because Americans aren’t as familiar with David Frost as us Brits are — his embodiment of the man is spot-on), and doing so in a story that’s inherently compelling (even if somewhat embellished from reality — but hey, that’s the movies!), what more do you need?

* Many of those only in technical categories, but hey, an Oscar nom is an Oscar nom. ^

(2016)

Garth Davis | 119 mins | streaming (HD) | 2.35:1 | UK, Australia & USA / English, Hindi & Bengali | PG / PG-13

Slumdog Millionaire meets Google product placement in this film, which is remarkably based on a true story — or based on a remarkable true story, if you want to be kinder. It’s the story of Saroo Brierley, a young Indian boy (played by newcomer Sunny Pawar) who is separated from his family, ends up in an orphanage, and is adopted by Australian parents. As an adult (played by Dev Patel), he resolves to find his birthplace and family — using Google Earth.

If it was fiction then it’d be too fantastic to believe, but because it’s true it packs a strong emotional weight, not least Saroo’s relationship with is adoptive parents, played by Nicole Kidman and David Wenham. The star of the show, however, is Dev Patel. You may remember there was controversy about him being put up for Supporting Actor awards, deemed “category fraud” by some because Saroo is the lead role. Conversely, he shares it with young Sunny Pawar, and Patel doesn’t appear until almost halfway through the film. Well, the “category fraud” people are more on the money, and it’s testament to Patel’s performance that it doesn’t feel like he’s only in half the film. Pawar is great — both plausible and sweetly likeable — but while watching I didn’t realise the movie had a near 50/50 split between young and adult Saroo. Maybe this means the first half is pacier, but its not that the second part feels slow, more that Patel has to carry greater emotional weight.

Rooney Mara is also in the film, as adult Saroo’s girlfriend. Her character is in fact based on multiple real-life girlfriends, but it makes sense to consolidate them into one character for the sake of an emotional throughline. However, her storyline ultimately goes nowhere — it ends with Saroo asking her to “wait for me”. Did she? Did he go back to her? It’s not the point of the film — that’s about him finding his family, and after that emotional climax you don’t really want an epilogue about whether he gets back with his girlfriend or not — but it still feels like it’s left hanging. I suppose it isn’t — I guess we’re meant to presume she does wait for him and they get together when he returns and live happily ever after — but it doesn’t feel resolved. It shouldn’t matter — as I say, it’s not the point — but, because of that, it does.

So it’s not a perfect movie, but it packs enough of an emotional punch to make up for it.

Warwick Davis is the farmer who must return an abandoned baby, unaware it’s heir to a throne evil queen Jean Marsh doesn’t wish to relinquish. Intermittently aided by Val Kilmer’s Han Solo-ish vagabond, they must elude the queen’s forces, led by her daughter, Joanne Whalley.

Warwick Davis is the farmer who must return an abandoned baby, unaware it’s heir to a throne evil queen Jean Marsh doesn’t wish to relinquish. Intermittently aided by Val Kilmer’s Han Solo-ish vagabond, they must elude the queen’s forces, led by her daughter, Joanne Whalley. Screenwriter Peter Morgan (of

Screenwriter Peter Morgan (of  I presume the point of engaging with their personal lives away from the track was to add depth; to make sure it was a two-hander, rather than just about one or other of the drivers, and to ensure Hunt wasn’t just two-dimensional. However, without any growth on his part, or even some kind of active change, he’s just as flat, only now the star of some pointless scenes.

I presume the point of engaging with their personal lives away from the track was to add depth; to make sure it was a two-hander, rather than just about one or other of the drivers, and to ensure Hunt wasn’t just two-dimensional. However, without any growth on his part, or even some kind of active change, he’s just as flat, only now the star of some pointless scenes. If that narrative fits snuggly into familiar plot beats, what are you meant to do? Change the truth to make it less like fiction? That’d be a first. Saying that, I’m taking it on faith (based on comments in the making-of) that the true story was so perfect you wouldn’t believe it if it had been fiction. Maybe they did streamline it. But assuming it’s real… well, it’s not the filmmakers’ fault if life imitates art.

If that narrative fits snuggly into familiar plot beats, what are you meant to do? Change the truth to make it less like fiction? That’d be a first. Saying that, I’m taking it on faith (based on comments in the making-of) that the true story was so perfect you wouldn’t believe it if it had been fiction. Maybe they did streamline it. But assuming it’s real… well, it’s not the filmmakers’ fault if life imitates art. All in all, I’m a little surprised how well-liked Rush is. I mean, as of posting it’s at #162 on

All in all, I’m a little surprised how well-liked Rush is. I mean, as of posting it’s at #162 on  The big winner at the 2002 Oscars (four gongs from eight nominations), A Beautiful Mind adapts the true story of John Nash (Russell Crowe), a Cold War-era mathematics student at Princeton who hit upon a groundbreaking theory and ended up working covertly for the government…

The big winner at the 2002 Oscars (four gongs from eight nominations), A Beautiful Mind adapts the true story of John Nash (Russell Crowe), a Cold War-era mathematics student at Princeton who hit upon a groundbreaking theory and ended up working covertly for the government… but the display of range probably merited it; perhaps more so, in retrospect, than his win for Gladiator the year before.

but the display of range probably merited it; perhaps more so, in retrospect, than his win for Gladiator the year before. A Beautiful Mind won Best Picture in spite of being up against the incredibly more innovative, entertaining, and game-changing double-bill of

A Beautiful Mind won Best Picture in spite of being up against the incredibly more innovative, entertaining, and game-changing double-bill of  Back in this blog’s early days, I established the rule that where a different cut of a film was not significantly different to the original version it wouldn’t be counted towards my total (assuming I’d seen the original, that is — if it’s the first time I’ve seen any version of the film, it still counts). There’s no hard criteria for what counts as “significantly different” though. A couple of additional minutes? No. A lot of additional minutes? Yes. Where’s the line between “a couple” and “a lot”? No idea. Thus far, I’ve left it up to “a feeling”, perhaps not always correctly (the

Back in this blog’s early days, I established the rule that where a different cut of a film was not significantly different to the original version it wouldn’t be counted towards my total (assuming I’d seen the original, that is — if it’s the first time I’ve seen any version of the film, it still counts). There’s no hard criteria for what counts as “significantly different” though. A couple of additional minutes? No. A lot of additional minutes? Yes. Where’s the line between “a couple” and “a lot”? No idea. Thus far, I’ve left it up to “a feeling”, perhaps not always correctly (the  but other than that if you’d told me this was the cut I watched in cinemas I’d believe you. This longer cut doesn’t make the film better or worse, just less suitable for younger viewers.

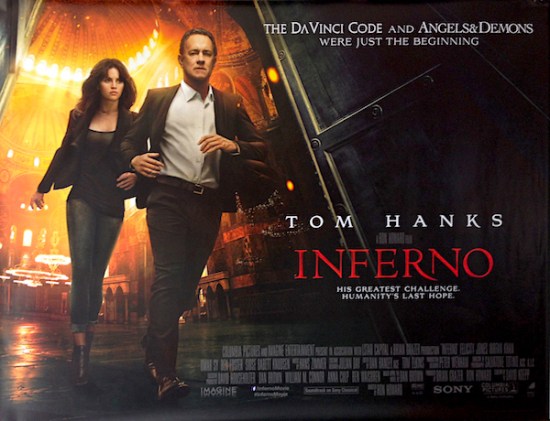

but other than that if you’d told me this was the cut I watched in cinemas I’d believe you. This longer cut doesn’t make the film better or worse, just less suitable for younger viewers. It’s still riddled with flaws, mind. Some of the dialogue is fairly atrocious (but at least it’s only some); exposition is often blatant and repetitive (we’re told what the preferiti are three or four times in as many minutes); some of the deductive leaps are a bit much; and the whole antimatter bomb still seems scientifically suspect. It all depends how much you’re willing to forgive, really. In a similar vein, one of the most contentious issues of Dan Brown’s novels is his use of “truth”. He mixes well-researched fact with his own creation at will, often leaving you to wonder if what you’re hearing is pure truth, truth bent to the plot, or a total fabrication. But then this isn’t a history or art lesson, it’s a mystery thriller, and if one wants to know more I’m sure there are books to read and documentaries to watch.

It’s still riddled with flaws, mind. Some of the dialogue is fairly atrocious (but at least it’s only some); exposition is often blatant and repetitive (we’re told what the preferiti are three or four times in as many minutes); some of the deductive leaps are a bit much; and the whole antimatter bomb still seems scientifically suspect. It all depends how much you’re willing to forgive, really. In a similar vein, one of the most contentious issues of Dan Brown’s novels is his use of “truth”. He mixes well-researched fact with his own creation at will, often leaving you to wonder if what you’re hearing is pure truth, truth bent to the plot, or a total fabrication. But then this isn’t a history or art lesson, it’s a mystery thriller, and if one wants to know more I’m sure there are books to read and documentaries to watch. In the Shadow of the Moon tells the story of NASA’s Apollo missions using only contemporary footage and the words of the men who actually walked on the Moon.

In the Shadow of the Moon tells the story of NASA’s Apollo missions using only contemporary footage and the words of the men who actually walked on the Moon.