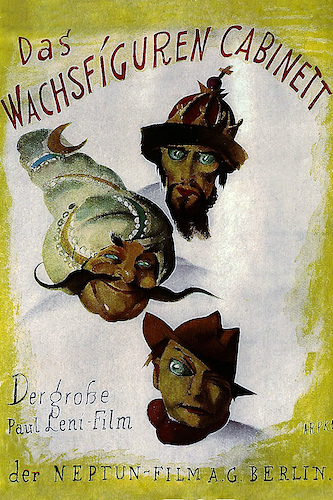

Paul Leni | 82 mins | digital (HD) | 1.33:1 | Germany / silent | PG

Often billed as the first portmanteau horror movie, Waxworks only fits the bill in the loosest sense: its “three stories” are actually two stories and a dream sequence, the first (and longest) of which is, if anything, a swashbuckling farce.

But I’m getting a little ahead of myself. The film begins with a young writer (William Dieterle, who would later become a Hollywood director, responsible for 1938 Best Picture winner The Life of Emile Zola, amongst others) who is hired to pen backstories for the four statues in a carnival wax museum. Yes, four — the filmmakers ran out of money before they could film the fourth tale. As he begins writing, into each story he injects both himself and the museum’s curator’s daughter (Olga Belajeff) as his love interest.

The first tale is set in Arabian Nights-style Bagdad (IMDb says this part inspired Douglas Fairbanks to make The Thief of Bagdad, but a quick look at their release dates shows Fairbanks’ film came out months before Waxworks), and concerns a lecherous Caliph (Emil Jannings) who sets his sights on wooing a baker’s wife. It’s quite a sexualised segment all round: the baker kneads dough so erotically it sends his wife (and himself) all aquiver (I doubt it’ll do the same for many viewers, but it clearly works for them); later, the disguised Caliph sneaks into the baker’s home and spies the wife lying in bed with her back to him, and his gaze (and, by extension, ours) clearly lingers on her bottom (clothed, lest you think the film is uncommonly explicit). I guess the characters were too busy perving to apply logic to their decision-making: when the baker is too wary to slip a ring off the sleeping Caliph’s finger, he decides to chop his whole arm off instead. Totally reasonable. Meanwhile, why is the all-powerful Caliph worried about being found out by a lowly baker? Indeed, why’s he so worried that his guards will know he sneaks out at night? He’s the boss! On the bright side, there’s some beautiful and striking Expressionist set design; an exciting chase scene, set to dramatic percussive music in the new score by Bernd Schultheis, Olav Lervik, and Jan Kohl; and the wife’s save at the climax is a cunning twist. But, overall, it’s a bit of a daft farce.

The second story stars Conrad Veidt as a Rasputin-esque Ivan the Terrible, who revels in killing prisoners in the Kremlin’s dungeons with an ultra-specifically-timed poison. If that wasn’t clue enough, this segment is thematically much darker. A bride’s father invites Ivan to attend the wedding, then the Czar insists they switch roles to travel there and the dad is killed by mistaken assassins. Then his arrow-pierced corpse is unceremoniously dumped on the front steps of his home while the wedding banquet continues inside; and when daughter sneaks away to grieve over his body, Ivan has some guards snatch her; and when the angry groom tries to attack Ivan, he’s ordered off to the torture chamber. Puts people who complain about rain on their wedding day into perspective, doesn’t it? Veidt is great as the deranged Ivan, although he’s so mentally unstable that it borders on comical. The finale doesn’t make much sense (he lets the girl go… then doesn’t?), but the denouement delivers a neat and fitting fate to Czar Terrible.

The third and final story begins with just five minutes of screen time left, so you know it’s not going to be wholly-realised tale. (Incidentally, the original German version of the film is lost, leaving us with only the English version, which is about 25 minutes shorter. What’s in those minutes? If anyone knows, they’re not saying online (to the best of my knowledge). Perhaps there was more linking material in the museum? Perhaps the third ‘story’ really was a whole story? Perhaps the first two were once even longer, though it’s hard to imagine how much more there could be to do in either of them — maybe the cuts were for the best…) Anyway, the third segment is the aforementioned dream sequence, in which the waxwork of Jack the Ripper comes to life and pursues the writer and his love (they met earlier that day but already seem pretty committed) through a series of highly impressionist sets, their disjointed oddity exacerbated by differently-aligned multiple exposures. It’s Expressionism to the max, and it’s suitably effective as a chiller. But, of course, it’s all a dream… and that’s suddenly the end!

Like so many of the portmanteau films that have followed in its wake, Waxworks struggles to be the sum of its parts. It’s ultimately a bit underwhelming, with the first two stories being slower than necessary (and this is the cut version!) before giving way to a rushed finale. Make no mistake, there’s some very nice stuff in here, but it comes in bits and pieces. It’s a welcome watch for fans of silent cinema or early horror (with caveats about its “horror” content duly noted), and there are enough good parts to recommend it, but I wouldn’t argue it’s a classic in any enduring sense (beyond its obvious influence as a stepping stone to future portmanteau films).

Waxworks is streaming on AMPLIFY! until 22nd November, and is released on Blu-ray as part of the Masters of Cinema Series today.

Also, new on AMPLIFY! today are…

- what sounds like a German riff on Whiplash, but with violins, in The Audition

- a documentary about the drawbacks of algorithms, Coded Bias

- the UK premiere of Viggo Mortensen’s directorial debut, Falling

- Catalan coming-of-age drama The Innocence

- and unusual found footage documentary My Mexican Bretzel.

(If you don’t know, “bretzel” is the German word for “pretzel”.)

Disclosure: I’m working for AMPLIFY! as part of FilmBath. However, all opinions are my own, and I benefit in no way (financial or otherwise) from you following the links in this post or making purchases.

Widely regarded as one of the greatest movies of all time (look at

Widely regarded as one of the greatest movies of all time (look at  Dreyer based his telling on the written records of Joan’s trial. Although that’s grand for claims of historical accuracy, it’s hard to deny that silent cinema is ill-suited to thoroughly portraying something dialogue-heavy. There are many things silent film can — and, in this case, does — do very well indeed, but representing extensive verbal debate isn’t one of them. Bits where the judges argue amongst themselves — in silence, as far as the viewer is concerned — leave you longing to know what it is they’re so het up about. Sometimes it becomes clear from how events transpire; other times, not so much.

Dreyer based his telling on the written records of Joan’s trial. Although that’s grand for claims of historical accuracy, it’s hard to deny that silent cinema is ill-suited to thoroughly portraying something dialogue-heavy. There are many things silent film can — and, in this case, does — do very well indeed, but representing extensive verbal debate isn’t one of them. Bits where the judges argue amongst themselves — in silence, as far as the viewer is concerned — leave you longing to know what it is they’re so het up about. Sometimes it becomes clear from how events transpire; other times, not so much. neutral costumes on sparsely-decorated sets, and are almost entirely shot in close-ups — all elements that avoid the usual grandiosity of historical movies, both in the silent era and since. What we perceive as being ‘grand’ changes over time (things that were once “epic” can become small scale in the face of increasing budgets, for instance); pure simplicity, however, does not age much.

neutral costumes on sparsely-decorated sets, and are almost entirely shot in close-ups — all elements that avoid the usual grandiosity of historical movies, both in the silent era and since. What we perceive as being ‘grand’ changes over time (things that were once “epic” can become small scale in the face of increasing budgets, for instance); pure simplicity, however, does not age much. The actors playing the judges may be less individually memorable than Joan, but it’s their conflict — the personal battle between Joan and these men, as Dreyer saw it — that drives the film. Dreyer believed the judges felt genuine sympathy for Joan; that they did what they did not because of politics (they represented England, and she had led several successful campaigns against the Brits) but because of their devout belief in religious dogma. Dreyer says he tried to show this in the film, though it strikes me the judges still aren’t portrayed too kindly: they regularly seem contemptuous of Joan, and are outright duplicitous at times. Maybe that’s just religion for you.

The actors playing the judges may be less individually memorable than Joan, but it’s their conflict — the personal battle between Joan and these men, as Dreyer saw it — that drives the film. Dreyer believed the judges felt genuine sympathy for Joan; that they did what they did not because of politics (they represented England, and she had led several successful campaigns against the Brits) but because of their devout belief in religious dogma. Dreyer says he tried to show this in the film, though it strikes me the judges still aren’t portrayed too kindly: they regularly seem contemptuous of Joan, and are outright duplicitous at times. Maybe that’s just religion for you. however, so I have no opinion. Instead, they offer two alternatives. On the correct-speed 20fps version, there’s a piano score by silent film composer Mie Yanashita. Apparently this is the only existing score set to 20fps, and Masters of Cinema spent so much restoring the picture that there was no money left to commission an original score. Personally, I don’t think they needed to. Yanashita’s is classically styled, which works best for the style of the film, and it heightens the mood of some sequences without being overly intrusive, by and large. Compared to Dreyer’s preferred viewing method, of course it affects the viewing experience — how could it not, when it marks out scenes (with pauses or a change of tone) and emphasises the feel of sequences (with changes in tempo, for instance). That’s what film music is for, really, so obviously that’s what it does. Would the film be purer in silence? Maybe. Better? That’s a matter of taste. This particular score is very good, though.

however, so I have no opinion. Instead, they offer two alternatives. On the correct-speed 20fps version, there’s a piano score by silent film composer Mie Yanashita. Apparently this is the only existing score set to 20fps, and Masters of Cinema spent so much restoring the picture that there was no money left to commission an original score. Personally, I don’t think they needed to. Yanashita’s is classically styled, which works best for the style of the film, and it heightens the mood of some sequences without being overly intrusive, by and large. Compared to Dreyer’s preferred viewing method, of course it affects the viewing experience — how could it not, when it marks out scenes (with pauses or a change of tone) and emphasises the feel of sequences (with changes in tempo, for instance). That’s what film music is for, really, so obviously that’s what it does. Would the film be purer in silence? Maybe. Better? That’s a matter of taste. This particular score is very good, though. Some viewers describe how they’ve found The Passion of Joan of Arc to be moving, affecting, or life-changing on a par with a religious experience. I wouldn’t go that far, but then I’m not religious so perhaps not so easily swayed. As a dramatic, emotional, film-viewing experience, however, it is highly effective. As Dreyer wrote in 1950, “my film on Joan of Arc has incorrectly been called an avant-garde film, and it absolutely is not. It is not a film just for theoreticians of film, but a film of general interest for everyone and with a message for every open-minded human being.” A feat of visual storytelling unique to cinema, it struck me as an incredible movie, surprisingly accessible, and, nearly 90 years after it was made, timeless.

Some viewers describe how they’ve found The Passion of Joan of Arc to be moving, affecting, or life-changing on a par with a religious experience. I wouldn’t go that far, but then I’m not religious so perhaps not so easily swayed. As a dramatic, emotional, film-viewing experience, however, it is highly effective. As Dreyer wrote in 1950, “my film on Joan of Arc has incorrectly been called an avant-garde film, and it absolutely is not. It is not a film just for theoreticians of film, but a film of general interest for everyone and with a message for every open-minded human being.” A feat of visual storytelling unique to cinema, it struck me as an incredible movie, surprisingly accessible, and, nearly 90 years after it was made, timeless.

Western with Barbara Stanwyck as a powerful landowner, and commander of the titular posse, whose bullying brother, Brockie, is consequently allowed to run riot over the town. Enter lawman Griff (Barry Sullivan) and his two brothers, whose moves to bring Brockie in line kickstart a chain of ruinous events.

Western with Barbara Stanwyck as a powerful landowner, and commander of the titular posse, whose bullying brother, Brockie, is consequently allowed to run riot over the town. Enter lawman Griff (Barry Sullivan) and his two brothers, whose moves to bring Brockie in line kickstart a chain of ruinous events.

A bomb is stuck to the underside of a car. As the vehicle pulls away, the camera drifts up into the sky, and proceeds to follow the automobile through the streets of a small Mexican border town, until it crosses the border into the US… and explodes. It’s probably the most famous long take in film history, and probably the thing Touch of Evil is most widely known for; that, and it being one of the most commonly-cited points at which the classic film noir era comes to an end.

A bomb is stuck to the underside of a car. As the vehicle pulls away, the camera drifts up into the sky, and proceeds to follow the automobile through the streets of a small Mexican border town, until it crosses the border into the US… and explodes. It’s probably the most famous long take in film history, and probably the thing Touch of Evil is most widely known for; that, and it being one of the most commonly-cited points at which the classic film noir era comes to an end. It’s like a terrible fever dream, with events and characters that sometimes seem disconnected, but nonetheless interweave through a dense plot. In this sense Welles puts us quite effectively in the shoes of Vargas and his wife — out of our depth, out of our comfort zone, out of control, struggling to keep up and keep afloat. It might be unpleasant if it wasn’t so engrossing.

It’s like a terrible fever dream, with events and characters that sometimes seem disconnected, but nonetheless interweave through a dense plot. In this sense Welles puts us quite effectively in the shoes of Vargas and his wife — out of our depth, out of our comfort zone, out of control, struggling to keep up and keep afloat. It might be unpleasant if it wasn’t so engrossing. Quinlan at all… there is not the least spark of genius in him; if there does seem to be one, I’ve made a mistake.” You can get pretentious about it all you want, and bring to bear political views that the film doesn’t support (after all, within the film Quinlan is punished for his crimes and the “mediocre” (Truffaut’s word) moral hero triumphs), but sometimes a spade is a spade; sometimes a villain is a villain; sometimes your disgusting moral perspective isn’t being covertly supported by a film that seems to condemn it.

Quinlan at all… there is not the least spark of genius in him; if there does seem to be one, I’ve made a mistake.” You can get pretentious about it all you want, and bring to bear political views that the film doesn’t support (after all, within the film Quinlan is punished for his crimes and the “mediocre” (Truffaut’s word) moral hero triumphs), but sometimes a spade is a spade; sometimes a villain is a villain; sometimes your disgusting moral perspective isn’t being covertly supported by a film that seems to condemn it. Notably and obviously absent from that list is Touch of Evil. It was taken away from Welles during the editing process, and though he submitted an infamous 58-page memo of suggestions after seeing a later rough cut, only some were followed in the version ultimately released. Time has brought change, however, and there are now multiple versions of Touch of Evil for the viewer to choose from; but whereas history often resolves one version of a film to be the definitive article, it’s hard to know which that is in this case. Indeed, it’s so contentious that Masters of Cinema went so far as to include five versions on their 2011 Blu-ray (it would’ve been six, but Universal couldn’t/wouldn’t supply the final one in HD.) The version I chose to watch, dubbed the “Reconstructed Version”, tries to recreate Welles’ vision, using footage from the theatrical cut and a preview version discovered in the ’70s to follow his notes. Despite the best intentions of its creators, this can only ever be an attempt at restoring what Welles wanted. Equally, although it was the version originally released, the theatrical cut ignores many of the director’s wishes — so as neither version was finished by Welles, surely the one created by people trying to enact his wishes is preferable to the one assembled by people who only took his ideas on advisement?

Notably and obviously absent from that list is Touch of Evil. It was taken away from Welles during the editing process, and though he submitted an infamous 58-page memo of suggestions after seeing a later rough cut, only some were followed in the version ultimately released. Time has brought change, however, and there are now multiple versions of Touch of Evil for the viewer to choose from; but whereas history often resolves one version of a film to be the definitive article, it’s hard to know which that is in this case. Indeed, it’s so contentious that Masters of Cinema went so far as to include five versions on their 2011 Blu-ray (it would’ve been six, but Universal couldn’t/wouldn’t supply the final one in HD.) The version I chose to watch, dubbed the “Reconstructed Version”, tries to recreate Welles’ vision, using footage from the theatrical cut and a preview version discovered in the ’70s to follow his notes. Despite the best intentions of its creators, this can only ever be an attempt at restoring what Welles wanted. Equally, although it was the version originally released, the theatrical cut ignores many of the director’s wishes — so as neither version was finished by Welles, surely the one created by people trying to enact his wishes is preferable to the one assembled by people who only took his ideas on advisement? To quote from Master of Cinema’s booklet, “the familiar Wellesian framing appears in 1.37:1: indeed, the “world” of the film setting emerges with little or no empty space at the top and bottom of the frame, almost certainly beyond mere coincidence.” There are things to recommend the widescreen experience (“a more tightly-wound, claustrophobic atmosphere”), and undoubtedly the debate will continue… and such is the wonders of the modern film fan that, rather than having to make do with someone else’s decision on what to put out, all the alternatives are at our fingertips.

To quote from Master of Cinema’s booklet, “the familiar Wellesian framing appears in 1.37:1: indeed, the “world” of the film setting emerges with little or no empty space at the top and bottom of the frame, almost certainly beyond mere coincidence.” There are things to recommend the widescreen experience (“a more tightly-wound, claustrophobic atmosphere”), and undoubtedly the debate will continue… and such is the wonders of the modern film fan that, rather than having to make do with someone else’s decision on what to put out, all the alternatives are at our fingertips. From the very start, Die Puppe sets out its stall (literally) as being something a bit special. The first sequence sees director Ernst Lubitsch himself unpack and assemble a doll’s house set and two dolls, which then become life-size and the dolls — now humans — the first characters we meet. It’s a neat framing device, a joke in itself, and some kind of early commentary on the role of a director.

From the very start, Die Puppe sets out its stall (literally) as being something a bit special. The first sequence sees director Ernst Lubitsch himself unpack and assemble a doll’s house set and two dolls, which then become life-size and the dolls — now humans — the first characters we meet. It’s a neat framing device, a joke in itself, and some kind of early commentary on the role of a director.