Ritesh Batra | 99 mins | download (HD) | 2.35:1 | India, France, Germany & USA / Hindi & English | PG / PG

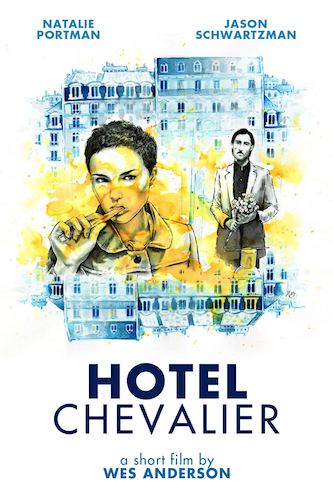

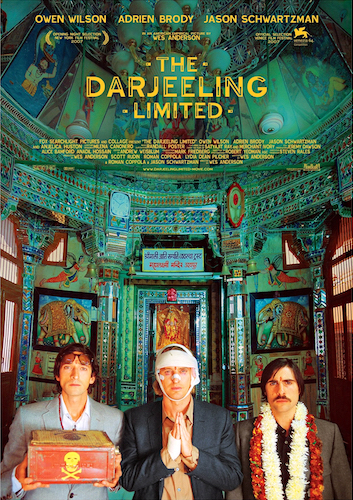

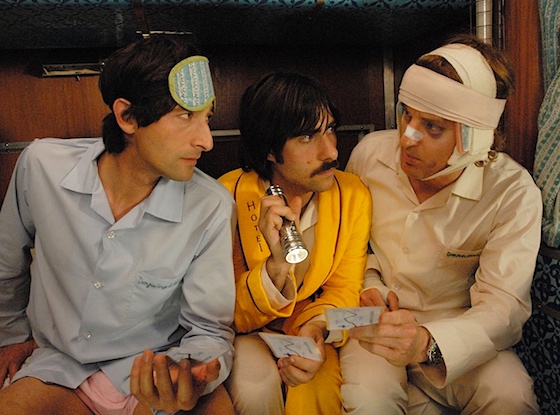

Yesterday the world heard the sad news that the actor Irrfan Khan had passed away aged just 53. An award-winning film star in India, Khan also had a noteworthy presence as a supporting actor in Western films — the police inspector in Slumdog Millionaire; the owner of the eponymous park in Jurassic World; the adult version of the main character in Life of Pi; not to mention The Darjeeling Limited, The Amazing Spider-Man, Inferno, and more. I’d seen all of those films and noted Khan’s presence — he’s the kind of actor who turns up and elevates the film almost just by being there, bringing a depth and interest to even the smallest roles. But I’d never seen any of the many films (he has 151 acting credits on IMDb) in which he played the lead, so it seemed appropriate to turn to one of the most internationally acclaimed of his films, The Lunchbox, in tribute.

Khan plays Saajan, an office worker who receives his lunch every day via the dabbawala service. It’s a remarkable network that delivers 200,000 lunches daily across Mumbai with unerring accuracy. Indeed, their precision is so famed that one of the major criticisms of this film in some quarters was that its premise is too far-fetched — that being that, due to a continued mixup, Saajan begins to receive the lunches Ila (Nimrat Kaur) has prepared for her husband, rather than the ones he ordered from a local restaurant. He’s so impressed with the quality of the food, when the lunchbox is returned Ila observes that it looks to have been licked clean. This is good news, because she was trying to up the quality of her lunches as a way to reignite her stagnant marriage; but when her husband returns home still disinterested, with only thin praise for something she hadn’t even included in his lunch, she realises the delivery mistake immediately. But politeness compels her to send lunch again, this time with a note explaining the mixup. After a rocky start, soon Saajan and Ila are in daily communication through short letters passed back and forth in the lunchbox.

Both are characters desperately in need of that connection. Ila’s loveless marriage, and young daughter who spends most of the day at school, means her primary human contact comes in shouted conversations with her upstairs neighbour. Saajan, meanwhile, is taking early retirement, but first must train Shaikh (Nawazuddin Siddiqui), the overeager new recruit appointed to replace him. He tries to duck even this level of interaction; at home, he tells off kids for playing in the road outside his house, refusing to return their ball. We could infer Saajan is a misanthrope, and the impression is given that his colleagues do (they share a story that he once kicked a cat in front of a bus then casually walked away), but the film affords us more insight than that, primarily through Khan’s performance. It’s the underlying sadness in his eyes that first give the clue to his true loneliness, and the way his demeanour begins to brighten as the relationship with Ila brings a spark back into his life.

Lest you think this is all somewhat dour, the way it plays is uplifting. Saajan and Ila may be miserable at the start, and continue to confront problems in their lives throughout the film, but their connection injects a measure of happiness into both their lives, the mutual support helping them through. Plus there’s a strong vein of humour, at first from the faltering beginnings of our leads’ relationship, then from the antics of Siddiqui’s junior employee. This isn’t the kind of broad comedy you might expect from a Bollywood movie, but something more grounded and closer to reality. At first Shaikh seems as irritating to us as he is to Saajan, but soon the latter’s growing empathy leads him to become a father figure to the younger man, and we too begin to see the truth underneath his cheery facade.

While that subplot is a bonus, the film really comes down to Saajan and Ila, and consequently the performances of Khan and Kaur. That’s particularly important because so much of the story occurs in the form of letters, and so the characters’ true reactions come across in doleful expressions, or changes in posture or behaviour; subtle, human indicators that leave us in no doubt what they’re feeling, and only strengthen our own connection to and investment in these characters. This pair of deeply-felt performances carefully steer The Lunchbox into being a heartfelt, quietly affecting film.

though this time there’s an added dose of romance in pretty much every plotline. It works because the cast are so darn good at delivering their material. Dev Patel and Maggie Smith are both hilarious, though everyone gets a moment to shine in the comedy stakes; conversely, Judi Dench and Bill Nighy carry the heart of the movie — though, again, everyone gets their emotional moment.

though this time there’s an added dose of romance in pretty much every plotline. It works because the cast are so darn good at delivering their material. Dev Patel and Maggie Smith are both hilarious, though everyone gets a moment to shine in the comedy stakes; conversely, Judi Dench and Bill Nighy carry the heart of the movie — though, again, everyone gets their emotional moment. In the impoverished Indian town of Malegaon, everyone either works on the power looms and is paid a pittance, or is unemployed and so has even less; apart from the women, who are squirrelled away out of sight at home. The population is 75% Muslim, the remainder Hindu, and that leads to tension. Outside of work, there is nothing to do for entertainment… except go to the movies. And Malegaon loves the movies.

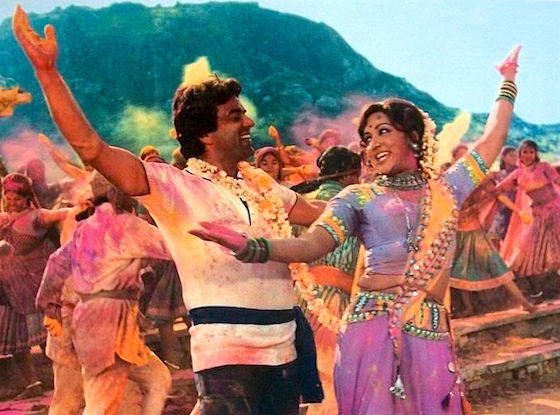

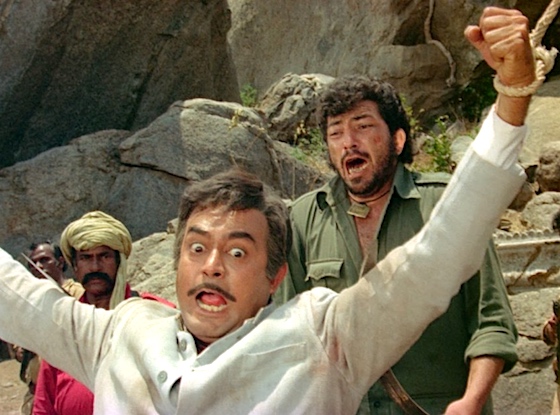

In the impoverished Indian town of Malegaon, everyone either works on the power looms and is paid a pittance, or is unemployed and so has even less; apart from the women, who are squirrelled away out of sight at home. The population is 75% Muslim, the remainder Hindu, and that leads to tension. Outside of work, there is nothing to do for entertainment… except go to the movies. And Malegaon loves the movies. Supermen of Malegaon is the making-of story of Nasir’s most ambitious production to date. Having seen the use of greenscreen in one of those behind-the-scenes outtakes, he realised he could use the process to make a special effects movie — specifically, to make Superman fly to Malegaon. This documentary follows the trials and tribulations of Nasir and his band of hobby filmmakers through their film’s writing, planning, and its sometimes troubled shoot, until it’s completed. In the process, we meet some genuine characters, learn something of the unique lifestyle of Malegaon itself, and maybe even learn something about ourselves too.

Supermen of Malegaon is the making-of story of Nasir’s most ambitious production to date. Having seen the use of greenscreen in one of those behind-the-scenes outtakes, he realised he could use the process to make a special effects movie — specifically, to make Superman fly to Malegaon. This documentary follows the trials and tribulations of Nasir and his band of hobby filmmakers through their film’s writing, planning, and its sometimes troubled shoot, until it’s completed. In the process, we meet some genuine characters, learn something of the unique lifestyle of Malegaon itself, and maybe even learn something about ourselves too. Even if it doesn’t, the situation in ‘Mollywood’ is an interesting one. This is a cottage industry: everyone involved has day jobs, funding the movies out of their own pocket, or by borrowing cash, or with favours, or by selling in-film adverts to local businesses — yes, that’s right, product placement, not that anyone involved would know that term. Women from Malegaon cannot appear in or work on the films due to local attitudes, so actresses are hired from nearby villages; the screenplay is written and shooting schedule arranged so that the actress only needs to be involved for the minimum number of days, to save money. Bicycles and motorbikes are used to create tracking shots; the director gets a piggyback for a high angle, or is raised and lowered on the arm of a cart to create a crane shot. The ingenuity and inventiveness of these literally-self-taught moviemakers is astonishing.

Even if it doesn’t, the situation in ‘Mollywood’ is an interesting one. This is a cottage industry: everyone involved has day jobs, funding the movies out of their own pocket, or by borrowing cash, or with favours, or by selling in-film adverts to local businesses — yes, that’s right, product placement, not that anyone involved would know that term. Women from Malegaon cannot appear in or work on the films due to local attitudes, so actresses are hired from nearby villages; the screenplay is written and shooting schedule arranged so that the actress only needs to be involved for the minimum number of days, to save money. Bicycles and motorbikes are used to create tracking shots; the director gets a piggyback for a high angle, or is raised and lowered on the arm of a cart to create a crane shot. The ingenuity and inventiveness of these literally-self-taught moviemakers is astonishing. which he turns down because he could make four whole films for that much money. Even that little is scraped together. Mollywood moviemaking isn’t a money spinner, it’s a hobby. Still, one of the writers wants to make it as a proper writer; wants to go to Bombay and do it as his career. This has been his aim for 15 years, he says, and Bombay is no closer.

which he turns down because he could make four whole films for that much money. Even that little is scraped together. Mollywood moviemaking isn’t a money spinner, it’s a hobby. Still, one of the writers wants to make it as a proper writer; wants to go to Bombay and do it as his career. This has been his aim for 15 years, he says, and Bombay is no closer. It’s an incredible, one-of-a-kind film; more powerful and life-affirming than it perhaps has any right to be. But then the filmmakers of Malegaon don’t really care about such things. They make movies because they want to, whether they ‘should’ or not; they make them better than you might expect; and it enriches their lives. Their story may do the same for you. In my opinion, it’s an essential film; a true must-see.

It’s an incredible, one-of-a-kind film; more powerful and life-affirming than it perhaps has any right to be. But then the filmmakers of Malegaon don’t really care about such things. They make movies because they want to, whether they ‘should’ or not; they make them better than you might expect; and it enriches their lives. Their story may do the same for you. In my opinion, it’s an essential film; a true must-see. British Army Captain Scott (Kenneth More) is charged with getting an Indian child prince and his American governess (Lauren Bacall) to safety as rebels attempt to murder him. With the palace under siege, their only hope is a barely-ready rust-bucket train engine, a single passenger carriage, and a long journey through enemy territory joined by a motley group of diplomats and hangers-on who’ve bargained their way on to this last train.

British Army Captain Scott (Kenneth More) is charged with getting an Indian child prince and his American governess (Lauren Bacall) to safety as rebels attempt to murder him. With the palace under siege, their only hope is a barely-ready rust-bucket train engine, a single passenger carriage, and a long journey through enemy territory joined by a motley group of diplomats and hangers-on who’ve bargained their way on to this last train. on the train by her governor husband, and Eugene Deckers is an arms dealer, who consequently no one likes but who remains unashamed of his trade. Through this prism there’s some discussion of the merits or otherwise of the British Empire and Indian independence, which some will judge to be extolling old-fashioned values, and others will take as little more than a (probably unnecessary) hat-tip in the direction of real politics.

on the train by her governor husband, and Eugene Deckers is an arms dealer, who consequently no one likes but who remains unashamed of his trade. Through this prism there’s some discussion of the merits or otherwise of the British Empire and Indian independence, which some will judge to be extolling old-fashioned values, and others will take as little more than a (probably unnecessary) hat-tip in the direction of real politics. North West Frontier, on the other hand, sounds like a Western — which was perhaps the intention: the film’s structure and story style is fundamentally a fit for that genre, albeit British-made and geographically relocated. The storyline immediately brings to mind John Ford’s

North West Frontier, on the other hand, sounds like a Western — which was perhaps the intention: the film’s structure and story style is fundamentally a fit for that genre, albeit British-made and geographically relocated. The storyline immediately brings to mind John Ford’s  2013 Academy Awards

2013 Academy Awards “Unfilmable” — now there’s an adjective you don’t hear tossed about so much these days. For a long time it seemed like it was all the rage to label novels “unfilmable”, but at this point too many ‘unfilmable’ novels have been filmed, and the wonders of CGI have put paid to anything ever again being unfilmable for practical or visual reasons. It may still be an apposite descriptor for works that feature very literary storytelling, though if you can render something like the subjective and unreliable narrator of

“Unfilmable” — now there’s an adjective you don’t hear tossed about so much these days. For a long time it seemed like it was all the rage to label novels “unfilmable”, but at this point too many ‘unfilmable’ novels have been filmed, and the wonders of CGI have put paid to anything ever again being unfilmable for practical or visual reasons. It may still be an apposite descriptor for works that feature very literary storytelling, though if you can render something like the subjective and unreliable narrator of  but because of almost-indefinable features of each shot’s crispness, its depth of field, even the compositions. It absolutely works in 2D, and it didn’t leave me longing for 3D in quite the same way as something like the swooping aerial sequences of

but because of almost-indefinable features of each shot’s crispness, its depth of field, even the compositions. It absolutely works in 2D, and it didn’t leave me longing for 3D in quite the same way as something like the swooping aerial sequences of  Later, the 4:3 “book cover” shot is just pure indulgence. There’s no reason not to just have empty sea to the left and right of frame, and the “it’s emulating the book cover!” reason/excuse doesn’t come close to passing muster simply because book covers aren’t 4:3. In both cases, then, what was intended to be striking or clever or innovative or in some way effective, I guess, comes across as pointless and distracting and pretentious.

Later, the 4:3 “book cover” shot is just pure indulgence. There’s no reason not to just have empty sea to the left and right of frame, and the “it’s emulating the book cover!” reason/excuse doesn’t come close to passing muster simply because book covers aren’t 4:3. In both cases, then, what was intended to be striking or clever or innovative or in some way effective, I guess, comes across as pointless and distracting and pretentious. Reading around a little online, it seems that some people have interpreted the film’s message as being a defence of/justification for/persuasion towards religious faith, and hate it for that. This interests me, because I — coming, I suspect, from a similar perspective on religion — read it as a subtle condemnation of religious stories. Actually, not a condemnation, but a tacit acceptance of the fact that such stories are a nice fairytale, but not the truth. To put it another way, I took the message to be (more or less) that religion is an obvious fiction which people choose to believe because it’s a nicer story than the more plausible alternative, neither of which are provable. I think some focus on the point that the journalist hearing Pi’s story is told it will make him believe in God, and, at the end, the journalist seems to accept that it does. I don’t think that’s the film’s contention, though; I think the film is, in a way, explaining why people believe in God. Or maybe there are just no easy answers.

Reading around a little online, it seems that some people have interpreted the film’s message as being a defence of/justification for/persuasion towards religious faith, and hate it for that. This interests me, because I — coming, I suspect, from a similar perspective on religion — read it as a subtle condemnation of religious stories. Actually, not a condemnation, but a tacit acceptance of the fact that such stories are a nice fairytale, but not the truth. To put it another way, I took the message to be (more or less) that religion is an obvious fiction which people choose to believe because it’s a nicer story than the more plausible alternative, neither of which are provable. I think some focus on the point that the journalist hearing Pi’s story is told it will make him believe in God, and, at the end, the journalist seems to accept that it does. I don’t think that’s the film’s contention, though; I think the film is, in a way, explaining why people believe in God. Or maybe there are just no easy answers. I found Life of Pi to be a little bit of a mixed bag, on the whole, where moments of transcendent wonder-of-cinema beauty rub up against instances of thumb-twiddling; where insightful or emotional revelations rub shoulders with pretentious longueurs. There is much to admire, but there are also parts to endure. The balance of reception lies in its favour, but while some love it unequivocally, a fair number seem to despise it with near-equal fervour. Either way, it’s definitely a film worth watching, and in the best possible quality you can manage, too. It also made me want to read the book, which for a movie I wasn’t even sure how much I liked is certainly an unusual, but positive, accomplishment.

I found Life of Pi to be a little bit of a mixed bag, on the whole, where moments of transcendent wonder-of-cinema beauty rub up against instances of thumb-twiddling; where insightful or emotional revelations rub shoulders with pretentious longueurs. There is much to admire, but there are also parts to endure. The balance of reception lies in its favour, but while some love it unequivocally, a fair number seem to despise it with near-equal fervour. Either way, it’s definitely a film worth watching, and in the best possible quality you can manage, too. It also made me want to read the book, which for a movie I wasn’t even sure how much I liked is certainly an unusual, but positive, accomplishment. As we head in to this year’s awards season, I’ve finally got round to seeing last year’s big winner. It’s the Little British Film That Could, and I do feel like I’m the last person in the country to see it.

As we head in to this year’s awards season, I’ve finally got round to seeing last year’s big winner. It’s the Little British Film That Could, and I do feel like I’m the last person in the country to see it.