The Best Foreign Language Film category at the 2011 Oscars is, in retrospect, a pretty impressive year. Alejandro González Iñárritu was already well established before his nominated film, Biutiful, but his fellow nominees included Yorgos Lanthimos for only his third feature, Dogtooth, and Denis Villeneuve for this, his second after his career re-start. And yet the winner was In a Better World. Remember that? Me neither. (I don’t even recall it ever being mentioned in the last near-decade-and-a-half; although its director was Susanne Bier, who’s gone on to the likes of The Night Manager and Bird Box, so that’s something). It seems like an odd choice for victor with the power of hindsight, but that’s hindsight for you. On the other hand, watching Incendies, it’s hard to see how anyone could ever have missed its incredible power. (Or maybe In a Better World is even better. I struggle to believe that possibility, but you never know… and probably never will, because who’s still watching it nowadays? It’s certainly not getting a Collector’s Edition-style 4K UHD release from a boutique label — unlike, say, Incendies.)

Incendies is, on the surface, one of those films that can sound off-puttingly heavy: it’s about generational trauma caused by a long-running war in the Middle East. Sure, that kind of thing can be Worthy and Great filmmaking, but egads, hard going. But while Incendies is all those things, it’s also a compelling mystery, which leads to twists worthy of a great thriller. The first of those comes in the film’s setup: Nawal, the mother of a pair of grownup twins has died, and it’s only from her will they learn, first, that their thought-dead father is still alive and, second, that they have an older brother they didn’t know existed. They are tasked with finding both men, and only then will they receive the final letter she has left for them. To do this, they must travel to their mother’s homeland, an unnamed Middle Eastern country (heavily inspired by Lebanon) where the aforementioned war is over, but the scars still linger. As they investigate their mother’s previous life, we see it play out in flashbacks.

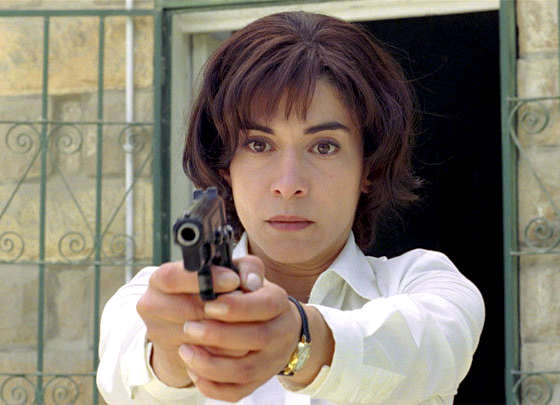

While the film at first seems to be about the twins, it’s really most about Nawal. That’s in part thanks to the incredible performance by Lubna Azabal. She has to portray this woman across decades, from a relative innocent to someone changed and hardened by all she’s been through, and charting every step of that journey, too. Plus, she’s left to convey almost all of that silently. Not that she’s mute, but she’s rarely allowed the shortcut of dialogue that discusses or exposes her emotions and motivations. That we still gain so much understanding of the how and why of Nawal is remarkable, really; a performance that, under different circumstances (let’s be honest: if it were in English) would surely have contended for every major award going.

The film is not about a specific conflict — that’s part of the reason playwright Wajdi Mouawad didn’t explicitly set his original work in Lebanon, and why Villeneuve ultimately didn’t change that when adapting it. Rather, as Villeneuve says, it’s “about the cycle of anger, the heritage of anger in a family, where in a conscious and subconscious way anger is traveling among family members, and among a society”. The point is not “what happened in Lebanon”, but what happens when families are torn apart, emotionally just as much as physically; what the fallout from that is, and how healing can be found — if, indeed, it can.

Oh dear, it’s all sounding a bit heavy again, isn’t it? And yes, there is an element of Incendies that is like that. It’s the kind of film that uses Radiohead on its soundtrack multiple times. (That said, this is how I feel that band’s dirge-like ambient-noise style of music functions best: as background mood-creating film score, rather than as, y’know, songs.) But, as I said before, this is also a film that plays as an effective mystery. What, exactly, happened to Nawal? Who and where is their father? Who and where is their older brother? Why was this a secret Nawal took to her grave? Why did she feel the need to reveal it posthumously? Any and all of these are questions your stereotypical “art house” movie would leave unanswered, providing vague prompts for you to consider after the film ends — or, inevitably, provoke you to Google “Incendies ending explained”. But Incendies isn’t actually like that — all of those questions are answered, because they’re essential to what the film is about. That they can also be gasp-inducing all-timer reveals is another bonus.

Within that, Villeneuve also shows off the expert filmmaking that has since elevated him to Christopher Nolan-adjacent levels of big-budget auteurist blockbuster-making. There’s a sequence on a bus in the middle of the film that is as tense as any suspense movie, as scary as any horror movie, and as emotionally devastating as any hard-hitting drama. There’s a reason it’s the inspiration for almost every poster and key art piece related to the film. (The exception is the original American theatrical poster, which shows… a woman standing by some sand. Great marketing, folks. Maybe that’s why it didn’t win the Oscar.) It’s an event of such horror that — especially when combined with the shocking revelations later in the film (which, obviously, I’m not going to spoil) — I imagine this is the kind of movie some people swear off ever watching again, like Requiem for a Dream; a big comparison, maybe, but one Incendies is up to.

Incendies is the 68th film in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2024. It was viewed as part of “What Do You Mean You Haven’t Seen All of the IMDb Top 250?”. At time of posting, it was ranked 101st on that list. It was my Favourite Film of the Month in September 2024. It placed 4th on my list of The Best Films I Saw in 2024.

Between his popular English-language debut

Between his popular English-language debut  While looking up those various explanations, I read at least one review that asserted it’s a good thing that the film doesn’t provide a clear answer at the end. Well, I think that’s a debatable point. I mean, there is an answer — Villeneuve & co clearly know what they’re doing, to the point where they made the actors sign contracts that forbade them from revealing too much to the press. So why is it “a good thing” that they choose to not explain that answer in the film? This isn’t just a point about Enemy, it’s one we can apply more widely. There’s a certain kind of film critic/fan who seems to look down on any movie that ends with an explanation for all the mysteries you’ve seen, but if you give them a movie where those mysteries do have a definite answer but it’s not actually provided as part of the film, they’re in seventh heaven. (And no one likes a movie where there are mysteries but no one has an answer for them, do they? That’d just be being mysterious for precisely no purpose.) But why is this a good thing? Why is it good for there to be answers but not to give them, and bad for there to be answers and to provide them too? If the answers the filmmakers intended are too simplistic or too pat or too well-worn or too familiar, then they’re poor for that reason, and surely they’re still just as poor if you don’t readily provide them? I rather like films that have mysteries and also give me the answers to those mysteries. Is that laziness on my part? Could be. But I come back to this: if, as a filmmaker (or novelist or whatever) you have an answer for your mystery and you don’t give it in the text itself, what is your reason for not giving it in the text? Because I think perhaps you need one.

While looking up those various explanations, I read at least one review that asserted it’s a good thing that the film doesn’t provide a clear answer at the end. Well, I think that’s a debatable point. I mean, there is an answer — Villeneuve & co clearly know what they’re doing, to the point where they made the actors sign contracts that forbade them from revealing too much to the press. So why is it “a good thing” that they choose to not explain that answer in the film? This isn’t just a point about Enemy, it’s one we can apply more widely. There’s a certain kind of film critic/fan who seems to look down on any movie that ends with an explanation for all the mysteries you’ve seen, but if you give them a movie where those mysteries do have a definite answer but it’s not actually provided as part of the film, they’re in seventh heaven. (And no one likes a movie where there are mysteries but no one has an answer for them, do they? That’d just be being mysterious for precisely no purpose.) But why is this a good thing? Why is it good for there to be answers but not to give them, and bad for there to be answers and to provide them too? If the answers the filmmakers intended are too simplistic or too pat or too well-worn or too familiar, then they’re poor for that reason, and surely they’re still just as poor if you don’t readily provide them? I rather like films that have mysteries and also give me the answers to those mysteries. Is that laziness on my part? Could be. But I come back to this: if, as a filmmaker (or novelist or whatever) you have an answer for your mystery and you don’t give it in the text itself, what is your reason for not giving it in the text? Because I think perhaps you need one. Fortunately, Enemy has much to commend aside from its confounding plot. Gyllenhaal’s dual performance is great, making Adam and Anthony distinct in more ways than just their clothing (which is a help for the viewer, but not for the whole film), and conveying the pair’s mental unease really well. It would seem he errs towards this kind of role, from his name-making turn in

Fortunately, Enemy has much to commend aside from its confounding plot. Gyllenhaal’s dual performance is great, making Adam and Anthony distinct in more ways than just their clothing (which is a help for the viewer, but not for the whole film), and conveying the pair’s mental unease really well. It would seem he errs towards this kind of role, from his name-making turn in

Fighting a losing war against Mexican drug cartels in Arizona, FBI agent Kate Macer (Emily Blunt) is keen to be enlisted to an interagency task force run by Department of Defense consultant Matt Graver (Josh Brolin). Taken along for the ride but kept in the dark, Macer becomes increasingly concerned that all is not as it seems — especially when it comes to Alejandro (Benicio Del Toro), a mysterious task force member whose motives seem to be a big secret…

Fighting a losing war against Mexican drug cartels in Arizona, FBI agent Kate Macer (Emily Blunt) is keen to be enlisted to an interagency task force run by Department of Defense consultant Matt Graver (Josh Brolin). Taken along for the ride but kept in the dark, Macer becomes increasingly concerned that all is not as it seems — especially when it comes to Alejandro (Benicio Del Toro), a mysterious task force member whose motives seem to be a big secret… Arguably, the film loses its way a little when it does reach that point. Answers are forthcoming eventually, and the third act occasionally abandons the conflicted and complex world that came before it for more straightforward and satisfying turns of events. Fortunately, the film survives such wobbles thanks to the strengths it’s already established, and with an even deeper dive into moral greyness even while it seems to be offering a simplistically fulfilling climax.

Arguably, the film loses its way a little when it does reach that point. Answers are forthcoming eventually, and the third act occasionally abandons the conflicted and complex world that came before it for more straightforward and satisfying turns of events. Fortunately, the film survives such wobbles thanks to the strengths it’s already established, and with an even deeper dive into moral greyness even while it seems to be offering a simplistically fulfilling climax. Brolin may be a headline lead alongside those two, but his character is given little to work with beyond being a son-of-a-bitch who keeps Macer onside with (deceitful) charm. He’s fine but unremarkable in that role. Perhaps

Brolin may be a headline lead alongside those two, but his character is given little to work with beyond being a son-of-a-bitch who keeps Macer onside with (deceitful) charm. He’s fine but unremarkable in that role. Perhaps  Tension is definitely the name of the game when it comes Jóhann Jóhannsson’s score, which was also Oscar nominated. Dominated by elongated, heavy strings and pacey, heartbeat-emulating percussion, it makes the threats lurking in every corner feel tangible; makes the sense that everything is doomed and liable to go south at any moment palpable. It’s a major contributor to the film’s mood.

Tension is definitely the name of the game when it comes Jóhann Jóhannsson’s score, which was also Oscar nominated. Dominated by elongated, heavy strings and pacey, heartbeat-emulating percussion, it makes the threats lurking in every corner feel tangible; makes the sense that everything is doomed and liable to go south at any moment palpable. It’s a major contributor to the film’s mood. Yesterday I wrote about

Yesterday I wrote about  There’s a lot going on in Prisoners. While the basic format is straightforward, it’s realised in the form of a multi-stranded narrative full of well-drawn characters with complications of their own. Jackman and Gyllenhaal may be top billed and on the poster (well, an air-brushed waxwork vague approximation of Jackman was on

There’s a lot going on in Prisoners. While the basic format is straightforward, it’s realised in the form of a multi-stranded narrative full of well-drawn characters with complications of their own. Jackman and Gyllenhaal may be top billed and on the poster (well, an air-brushed waxwork vague approximation of Jackman was on  He’s not a bad detective, just not the usual genius-level investigator you normally find in thrillers, and at times you feel he’s muddling his way through the investigation as best he can. Aside from giving Loki the slightly-affected tic of blinking too much, Gyllenhaal offers a reasonably restrained performance. (I’d love to know what the blinking was in aid of, but the film is woefully understocked with special features.)

He’s not a bad detective, just not the usual genius-level investigator you normally find in thrillers, and at times you feel he’s muddling his way through the investigation as best he can. Aside from giving Loki the slightly-affected tic of blinking too much, Gyllenhaal offers a reasonably restrained performance. (I’d love to know what the blinking was in aid of, but the film is woefully understocked with special features.) Denis Villeneuve’s direction gives the sense of a non-Hollywood background with the occasional arty shot choice or composition, though not to a distracting extent. He’s aided by serial Oscar loser Roger Deakins on DP duty, who once again demonstrates why he shouldn’t have a golden man already, he should have a cupboard full. The photography here doesn’t flaunt itself with hyper-grading or endless visual trickery, but is consistently rich and varied. Deakins may also be the best action cinematographer working — pair what he brought to

Denis Villeneuve’s direction gives the sense of a non-Hollywood background with the occasional arty shot choice or composition, though not to a distracting extent. He’s aided by serial Oscar loser Roger Deakins on DP duty, who once again demonstrates why he shouldn’t have a golden man already, he should have a cupboard full. The photography here doesn’t flaunt itself with hyper-grading or endless visual trickery, but is consistently rich and varied. Deakins may also be the best action cinematographer working — pair what he brought to  As a thriller that is also a drama about people caught up in those events, and the lengths to which some of them may be prepared to go, Prisoners is a must-see for anyone with the stomach for some dark material (though don’t let me overemphasise that point — it’s not as bleak as, say,

As a thriller that is also a drama about people caught up in those events, and the lengths to which some of them may be prepared to go, Prisoners is a must-see for anyone with the stomach for some dark material (though don’t let me overemphasise that point — it’s not as bleak as, say,