W.D. Richter | 103 mins | Blu-ray | 2.35:1 | USA / English | 12 / PG

Buckaroo Banzai seems to have quite the cult following in the US, but, as far as I understand, it never made an impression over here; not until the internet enabled such cults to go global, anyway. It has big-name fans (one, Kevin Smith, was developing a remake for Amazon until legal wrangles got in the way), so of course it’s been noticed in more recent times. I’ve been somehow aware of it for ages, but finally got round to seeing it last year after Arrow put it out on Blu-ray.*

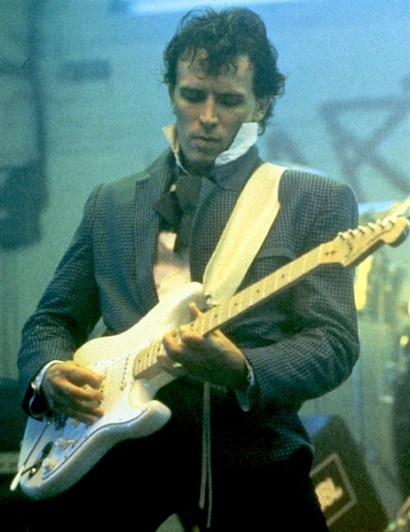

For those equally unfamiliar with the film, it’s an action-adventure sci-fi satirical comedy (kinda), concerning an adventure (one of many, I imagine) of Dr. Buckaroo Banzai (RoboCop’s Peter Weller), the famous physicist, neurosurgeon, test pilot, and rock musician. While testing a device that allows him to pass through solid matter, Banzai briefly travels to another dimension. This kickstarts a series of events that leads to the escape of evil aliens the Red Lectroids, who Banzai must defeat lest it brings about the end of the world. That’s the streamlined version, anyway.

To be perfectly honest, I’ve found it quite hard to tell what I thought of Buckaroo Banzai. On the one hand, I can definitely see where it gets its cult appeal, and I appreciate some of the ways it’s being different and boundary pushing. On the other, there’s been a definite backlash to it and I can appreciate where that comes from too — the criticism that some of that “boundary pushing” is merely sloppy storytelling and crazy overacting. There are parts where it’s hard to tell if it was deliberate and quite clever, or just incompetently done. Part of the problem (but also the appeal) is that it’s played so straight. It’s unquestionably a comedy — it’s too ludicrous to be anything else, and the sheer build-up of comedic lines becomes clear as it goes on — but it’s all played with such a straight face that I can see why you’d think everyone involved believed they were making something serious.

There are ways it could be ‘normal’, too: it contains so many elements that could be used to construct a traditional narrative — a new member being introduced to the gang, a love interest, an inciting incident which kicks off the events of the narrative, and so on — but it chooses to use none of these in a traditional way, instead being batshit crazy and thoroughly unique with it. Interestingly, director W.D. Richter was also one of the writers on Big Trouble in Little China, which is another action-adventure movie featuring a similar loose, crazy, fever-dream style. (Of all things, he also wrote Stealth, the forgotten-as-soon-as-it-was-released jet-pilots-vs-AI action thriller starring Jessica Biel and Jamie Foxx from 2005.) I can see how, after a diet of mainstream adventure cinema, something like this could feel refreshing. It’s almost like counter-culture pulp; like a Rocky Horror for the ’80s, but without the camp. (Or, at least, not the same kind of camp — I mean, have you seen what Jeff Goldblum’s wearing?)

In the booklet accompanying Arrow’s Blu-ray, James Oliver talks about cult movies and their history. “Cult” is sometimes used nowadays as a catch-all term for anything in the broad sci-fi / fantasy / horror realm, or with a dedicated and eager fanbase. It’s almost mainstream. The term’s roots lie in the opposite direction, of course — films that critics and mass moviegoers disliked but that developed a following of people who appreciate and defended them nonetheless. This is a lot easier and quicker than it used to be since VHS came along, and even more so in the era of DVD and Blu-ray. Banzai was possibly the first cult film to benefit in this way. Oliver concludes by reasoning that the film “resists easy assimilation. It plays too many games to be embraced by everyone and is, accordingly, often patronised or even denigrated, even by some of those who usually like cult movies. But such resistance just makes those who love it love it just that little bit harder. So it is a cult movie and, no matter how much the meaning of that phrase may mutate over time, it likely always will be.” Based on the aforementioned backlash — how it’s had a chance to move in a more widely-known direction but hasn’t done so — I think he’s right.

Personally, I’m still conflicted. I sort of didn’t think it was all that great, but also loved it at the same time. “Loved” might be too strong a word. I admired some of the ways it was different from the norm. Plus there are some very quotable lines, and the music that kicks off the end credits is relentlessly hummable. On balance, I really wanted to like it more than I actually did like it. Maybe I’ll get there on repeat viewings (because we know how good I am at getting round to those…)

* Said Blu-ray was actually released two years ago this month — where does time go?! ^

By many accounts this is the greatest film I’d never seen (hence it being this year’s pick for #100). How are you meant to go about approaching something like that? Probably by not thinking about it too much. I mean, something will always be “the greatest you’ve never seen”, even if you dedicate yourself to watching great movies and the “greatest you’ve never seen” is something pretty low on the list… at which point I guess it stops mattering.

By many accounts this is the greatest film I’d never seen (hence it being this year’s pick for #100). How are you meant to go about approaching something like that? Probably by not thinking about it too much. I mean, something will always be “the greatest you’ve never seen”, even if you dedicate yourself to watching great movies and the “greatest you’ve never seen” is something pretty low on the list… at which point I guess it stops mattering. Hollywood is notorious for adapting novels by grafting on happier endings, but here they did the opposite, removing even the glimmers of justice that the novel offers. In the book (according to Wikipedia), when McMurphy strangles Ratched he also exposes her breasts, humiliating her in front of the inmates; when she returns to work, her voice — her main instrument of control — is gone, and many of the inmates have either chosen to leave or have been transferred away. Conversely, in the film there is no humiliation, and we explicitly see that she still has her voice and that all the men are still there. Of course, McMurphy’s ultimate end isn’t cheery in either version. It’s almost like the anti-

Hollywood is notorious for adapting novels by grafting on happier endings, but here they did the opposite, removing even the glimmers of justice that the novel offers. In the book (according to Wikipedia), when McMurphy strangles Ratched he also exposes her breasts, humiliating her in front of the inmates; when she returns to work, her voice — her main instrument of control — is gone, and many of the inmates have either chosen to leave or have been transferred away. Conversely, in the film there is no humiliation, and we explicitly see that she still has her voice and that all the men are still there. Of course, McMurphy’s ultimate end isn’t cheery in either version. It’s almost like the anti-

If you’re on social media (or even just frequent pop culture news sites), you can’t fail to have noticed that Wednesday just passed was “Back to the Future Day”, the exact date Marty McFly and Doc Brown (and Marty’s girlfriend) travel to in

If you’re on social media (or even just frequent pop culture news sites), you can’t fail to have noticed that Wednesday just passed was “Back to the Future Day”, the exact date Marty McFly and Doc Brown (and Marty’s girlfriend) travel to in  Then it moves on to the fans — what the film means to them, and what that’s led them to do. Those we meet include a couple who travel around the US in a DeLorean fundraising for Michael J. Fox’s charity; the team of aficionados who restored Universal Studios’ decrepit display DeLorean; the family of collectors who own the only film-used DeLorean that will ever be in private ownership; a guy who built a mini-golf course in his yard with a Back to the Future-themed hole that he’s used for charity events with some of the films’ cast; the people who have had some success developing a real-life hoverboard; and the guy who set up a fansite that was so good it became the official site, and is now regularly employed as an official consultant about the films, not least for the rafts of merchandise that comes out these days. We also get a look at the Secret Cinema event in London from a year or two ago that made headlines for all the wrong reasons. Naturally, none of that gets mentioned here (in fairness, because it has nothing to do with Back to the Future itself).

Then it moves on to the fans — what the film means to them, and what that’s led them to do. Those we meet include a couple who travel around the US in a DeLorean fundraising for Michael J. Fox’s charity; the team of aficionados who restored Universal Studios’ decrepit display DeLorean; the family of collectors who own the only film-used DeLorean that will ever be in private ownership; a guy who built a mini-golf course in his yard with a Back to the Future-themed hole that he’s used for charity events with some of the films’ cast; the people who have had some success developing a real-life hoverboard; and the guy who set up a fansite that was so good it became the official site, and is now regularly employed as an official consultant about the films, not least for the rafts of merchandise that comes out these days. We also get a look at the Secret Cinema event in London from a year or two ago that made headlines for all the wrong reasons. Naturally, none of that gets mentioned here (in fairness, because it has nothing to do with Back to the Future itself). That glaring error aside, Back in Time is not a bad film, provided you know what to expect. It’s a shade too long and the storytelling is occasionally a little jumbled, but there are some nice interviews and stories — hearing Michael J. Fox recount the Royal Premiere where he was sat next to Princess Diana pretty much makes the whole exercise worthwhile.

That glaring error aside, Back in Time is not a bad film, provided you know what to expect. It’s a shade too long and the storytelling is occasionally a little jumbled, but there are some nice interviews and stories — hearing Michael J. Fox recount the Royal Premiere where he was sat next to Princess Diana pretty much makes the whole exercise worthwhile. Belated sequels can be a

Belated sequels can be a  But the comic-book-ness of the first film — moments of almost metaphorical visual representation rather than literal reality, including physically-impossible action beats — has been ramped up. The value of the first film was never in its action, so the sequel’s lengthy punch-ups, crossbow-based guard-slaying, and all the rest, get boring fast. When it slips into this needless excess, A Dame to Kill For loses its way. When it sticks to what it does best — hard-boiled fatalistic crime tales with striking comic book-inspired cinematography — it does as well as the concept ever did.

But the comic-book-ness of the first film — moments of almost metaphorical visual representation rather than literal reality, including physically-impossible action beats — has been ramped up. The value of the first film was never in its action, so the sequel’s lengthy punch-ups, crossbow-based guard-slaying, and all the rest, get boring fast. When it slips into this needless excess, A Dame to Kill For loses its way. When it sticks to what it does best — hard-boiled fatalistic crime tales with striking comic book-inspired cinematography — it does as well as the concept ever did. The intervening decade has lessened the impact of the first film’s sick ultra-violence, but there’s nothing even that extreme here, aside perhaps from one eyeball-related moment. On the other hand, nearly a decade of tech development means it looks better than the last one, both in terms of the CGI’s quality and the camerawork more generally — it’s less flatly shot; more filmic than the first one’s sometimes-webseries-y composition.

The intervening decade has lessened the impact of the first film’s sick ultra-violence, but there’s nothing even that extreme here, aside perhaps from one eyeball-related moment. On the other hand, nearly a decade of tech development means it looks better than the last one, both in terms of the CGI’s quality and the camerawork more generally — it’s less flatly shot; more filmic than the first one’s sometimes-webseries-y composition. its predecessor, and that’s exactly what it delivers. I suspect the first benefits from nostalgia because, watching them virtually back to back, I found I liked Sin City less than I remembered, but enjoyed A Dame to Kill For just as much. It’s flawed in several aspects, but for honest-to-themselves fans of the first movie, I think it’s a “more of what you liked”-style success.

its predecessor, and that’s exactly what it delivers. I suspect the first benefits from nostalgia because, watching them virtually back to back, I found I liked Sin City less than I remembered, but enjoyed A Dame to Kill For just as much. It’s flawed in several aspects, but for honest-to-themselves fans of the first movie, I think it’s a “more of what you liked”-style success. Although Disney have recently treated (I use the word loosely) us to a glut of films based on theme park attractions, movies adapted from good old board games seem a lot rarer. This is probably for good reason — even more so than Disney rides, the majority have no kind of useable narrative. Cluedo (aka Clue in the US) is one of the few that does, and consequently is one of the few (only?) board games that has reached the silver screen. So far, anyway.

Although Disney have recently treated (I use the word loosely) us to a glut of films based on theme park attractions, movies adapted from good old board games seem a lot rarer. This is probably for good reason — even more so than Disney rides, the majority have no kind of useable narrative. Cluedo (aka Clue in the US) is one of the few that does, and consequently is one of the few (only?) board games that has reached the silver screen. So far, anyway. Other than the board game connection, Clue is best known for its three different endings, all of which were released, with each screening having just one attached. On TV the film shows with all three consecutively, and they perhaps work best this way — there’s a rising scale of ridiculousness, and the varied repetition of a couple of gags underlines rather than steals their amusement value. My personal favourite variant was the first, incidentally.

Other than the board game connection, Clue is best known for its three different endings, all of which were released, with each screening having just one attached. On TV the film shows with all three consecutively, and they perhaps work best this way — there’s a rising scale of ridiculousness, and the varied repetition of a couple of gags underlines rather than steals their amusement value. My personal favourite variant was the first, incidentally.