I have a backlog of 515 unreviewed feature films from my 2018 to 2023 viewing. This is where I give those films their day, five at a time, selected by a random number generator.

Today, the main emergent theme is “films that weren’t so great” — although there are a couple of bright spots to be found, still.

This week’s Archive 5 are…

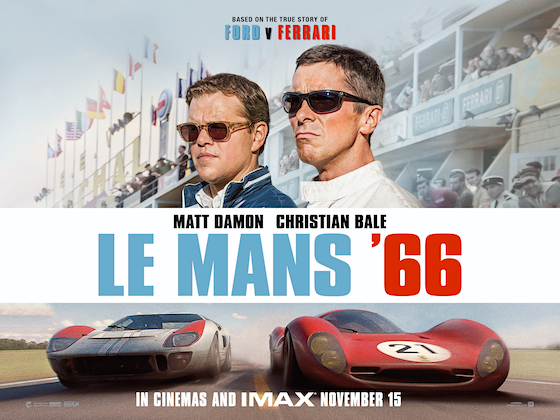

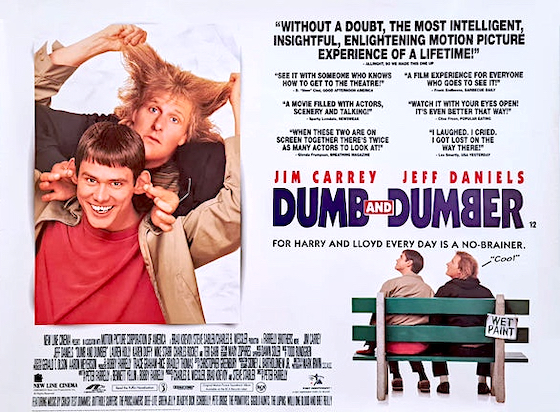

Dumb and Dumber

(1994)

Peter Farrelly | 107 mins | digital HD | 16:9 | USA / English | 12 / PG-13

The nicest thing I can say about Dumb and Dumber is that it does at least live up to its title: it starts dumb and gets dumber.

Despite the film’s later reputation in some circles as a modern comedy… if not “classic”, then certainly “success” — enough to eventually earn it both a prequel and sequel, at any rate — I’m clearly not alone in this view: apparently the original draft of the screenplay was so poor that it gained an enduringly negative reputation among investors; to the extent that, even once it had been rewritten, it had to be pitched under a fake title in order to get people to even read it. I feel like the final result only goes some way towards fixing that, with an oddly episodic structure and some bizarrely amateurish bits of filmmaking for a studio movie (the audio quality is relatively poor; there’s too much reliance on samey master shots).

There are a few genuinely funny bits between all the gurning, guffawing, and scatology. It’s a shame they’re not in an overall-better film.

Dumb and Dumber was #119 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2021. It featured on my list of The Worst Films I Saw in 2021.

Bill & Ted Face the Music

(2020)

Dean Parisot | 88 mins | digital HD | 2.39:1 | USA & Bahamas / English | PG / PG-13

I wasn’t that big a fan of the original Bill & Ted films, so I didn’t have high hopes for this — after all, most decades-later revival/reunion movies are primarily about trying to please existing fans, not win round new ones; and it feels like a good number of them fail even in that regard. Face the Music is definitely full of the requisite nods and references, both explicit and subtle, major and minor; but they’re all in the right spirit and it kinda works (albeit a bit scrappily at times), bound together by a deceptively simple, pervasive niceness.

Alex Winter is particularly great as Bill. Given all the stories we hear about how awesome Keanu Reeves is in real life, it’s no surprise that — despite being the much (much) bigger movie star — he’s generous enough to be a co-lead and let Winter shine. Brigette Lundy-Paine is absolutely bang on as Ted’s daughter, aping Reeves’ performance in all sorts of ways. As the younger Bill, Samara Weaving is clearly game, but doesn’t carry it quite as naturally (apparently she was cast after Reeves discovered she was the niece of Hugo Weaving, who he’d of course worked with on the Matrix trilogy, so that might explain that).

“Be excellent to each other” is a message the world needs now more than ever, and that’s as true four years on as it was back in 2020. For me, that makes this third outing Bill and Ted’s most excellent adventure.

Bill & Ted Face the Music was #136 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2021.

Mangrove

(2020)

aka Small Axe: Mangrove

Steve McQueen | 127 mins | TV HD | 2.39:1 | UK / English | 15

The line between film and TV continues to blur with Mangrove: a 127-minute episode of an anthology TV series, Small Axe, conceived and directed by Oscar winner Steve McQueen, that premiered as the opening night film of the London Film Festival. It was made for television, but in form and pedigree it’s a movie. Just another example in a “does it really matter?” debate that continues to rage — and is only likely to intensify with the increasing jeopardy faced by theatrical exhibition. (I wrote this intro almost four years ago, and while theatrical is fortunately still hanging in there post-pandemic, I do think the line remains malleable.)

I only ended up watching two episodes/films from Small Axe in the end. I did intend to go back and finish them, especially as they were heaped with critical praise, but the second (Lovers Rock) bored me to tears, which didn’t help. This first was better, but still not wholly to my taste. It tells an important true story about racially-motivated miscarriages of justice, but I found it overlong and with too much speechifying dialogue. That kind of thing works better in a courtroom setting, I find, so perhaps that’s why I felt the film was at its best once it (finally) got to the courtroom. When it’s good, it really is very good.

Mangrove was #246 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2020.

Out of Africa

(1985)

Sydney Pollack | 161 mins | digital HD | 16:9 | USA & UK / English | PG / PG

This is very much the kind of thing that was once considered a Great Movie, in an “Oscar winner” sense, but nowadays is sort of dated and attracts plenty of less favourable reviews. It’s long, historical, and white — not how we like our movies about Africa nowadays, for understandable reasons.

Certainly, there are inherent problems with its attitude to colonialism, but to a degree that’s tied to how much tolerance you have for “things were different in the past” as an argument for understanding. In this case, just because these white Europeans shouldn’t have taken African land and divvied it up among themselves and treated the inhabitants as little better than cattle, that doesn’t mean the individuals involved weren’t devoid of feeling or humanity. People like Karen, the film’s heroine, were trying to do what they thought was right within the limited scope of what society at the time allowed them to think. With the benefit of a more enlightened modern perspective, we can see that was still wrong and that they didn’t go far enough, but (whether you like it or not) there is an element of “things were different then”.

Morals aside, the story is a bit slow going, bordering on dull at times, but it’s mostly effective as a ‘prestige’ historical romance, which I think is what it primarily wants to be. It’s quite handsomely shot, although not as visually incredible as others make out, and John Barry’s score is nice — you can definitely hear it’s him: on several occasions it reminded me of the “love theme”-type pieces for his Bond work.

Out of Africa was #212 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2020.

Rambo: Last Blood

(2019)

Adrian Grünberg | 89 mins | digital HD | 2.39:1 | USA, Hong Kong, France, Bulgaria, Spain & Sweden / English & Spanish | 18 / R

Sylvester Stallone’s belated returns to the roles that made his name have worked out pretty well so far, I think, with Rocky Balboa and Rambo (i.e. Rambo 4) being among my favourites for both those franchises; not to mention Creed and its sequel. Unfortunately, here is where that streak runs out.

Running a brisk 89 minutes (in the US/Canada/UK cut — a longer version was released in other territories), the film is almost admirably to-the-point. We all know where it’s going, and more or less what plot beats it will hit along the way, so it doesn’t belabour anything, it just gets on with it. However, you eventually realise why other films ‘indulge’ in the kind of scenes this one has done away with: movies are about more than just plot, they’re about character and emotion and why things happen. Last Blood is so desperate to get to the action that it strips those things back to their bare minimum, thus undermining our investment. And then, weirdly, it hurries through the action scenes too. The climax packs in as many gruesome deaths in as short a time span as possible, meaning none but the most stomach-churning have any impact; and even those disgusting ones are mercifully fleeting. More, it feels rushed and of little consequence. Far from a grand send-off to the Rambo saga (which a slapped-on voiceover-and-montage finale attempts to evoke), it feels like a short-story interlude.

Did Rambo deserve better? Well, I wouldn’t necessarily go that far. But, on the evidence of this, it might be best if they don’t try again.

Rambo: Last Blood was #74 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2020.