I introduced the concept behind QT’s movie marathon in my previous roundup of films from it, but to quickly recap, these are all movies with a connection to Tarantino’s latest flick, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

While many of Tarantino’s selections speak to the setting of OUaTiH (in terms of depicting its time and place on screen, or the social landscape of its era), others have a bearing on it in quite a different way. These are movies his characters might’ve seen, or might’ve appeared in, or (in the case of Sharon Tate) did actually star in. Three of those also fall under the banner of espionage fiction. Two hail from the James Bond-inspired spy-fi craze of the ’60s, while one is a ’50s war movie about a secret mission. (Yeah, that last one is stretching the definition — it’s not really a spy movie at all — but it doesn’t pair up with anything else in Tarantino’s selection, so here it is.)

In today’s roundup:

(1968)

David Miller | 95 mins | TV | 16:9 | UK / English

The success of the James Bond movies led to a whole raft of imitators throughout the rest of the ’60s, a spy-fi craze that kickstarted other long-running franchises like Mission: Impossible and The Man from U.N.CL.E. Of course, as well as the memorable and enduring successes, there were piles of cheaply-made, entirely-forgettable knockoffs. Hammerhead is one of the latter. Like Bond, it’s based on a series of espionage novels, these ones by James Mayo (pen name of English novelist Stephen Coulter) and starring the character Charles Hood. Coulter had been friends with Ian Fleming, and apparently (according to Quentin Tarantino) his Hood novels were popular with secret agent fans because they were written in a similar style to Fleming. Hood didn’t have the staying power of Bond, though, the series running to just five novels which (as far as I can tell) haven’t been in print for decades. On film, he fared even less well: this is the only Charles Hood movie.

The film’s biggest problem is its desire to be a Bond movie, but without the money or panache to carry it off. As Hood, Vince Edwards has none of the easy charm of Sean Connery, instead seeming like a stick-in-the-mud who’d rather be anywhere else (preferably back in the ’50s, I suspect). And the film itself so wants to be like Bond that there’s even a pop song named after the titular villain… though rather than playing over the opening credits, it pops up two or three times mid-film, incongruously played diegetically. As a Letterboxd reviewer put it, “apparently in the late ’60s if you were a pornography-obsessed master criminal you could also be the subject of a pop song.”

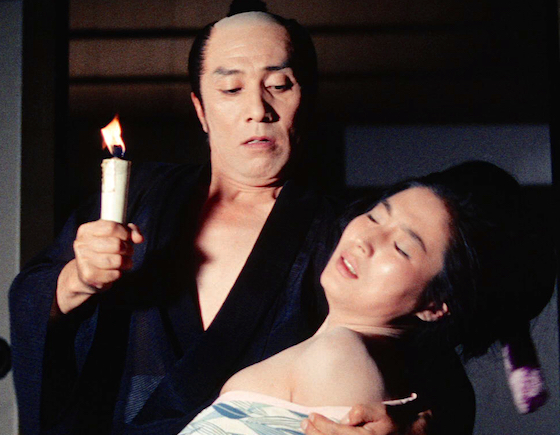

Oh yes, that’s right: the villain collects porn. Not just any old rags, though, but Art — paintings and sculptures by renowned masters, that kind of thing, just ones that feature boobies. Something about that does feel ever so ’60s. The film itself is as pervy as its villain’s obsession. Well, okay, maybe not that pervy, but there are certainly gratuitous shots of women in their underwear, etc. Perhaps the most egregious is the closeup of female co-lead Judy Geeson’s bouncing behind as she rides on the back of a motorbike up some steps, complete with boinging sound effect. That’s about as explicit as it gets, though: it may be firmly set in the Swinging Sixties, with up-to-the-minute fashions and scenes set at experimental art happenings, but it’s stuck in the past enough to not feature any actual sex or nudity, just plenty of cleavage, gyrating dance moves, and the odd bit of innuendo (don’t expect any Bond-quality puns, mind — it’s not that clever).

I haven’t mentioned the plot, but it’s a frequently nonsensical bit of nonsense involving a report so top-secret its author has to have a highly public cover story for what he’s supposed to be doing while he actually sneaking off to present to international delegates who’ve arrived in the country unannounced. If anyone ever said what this report was actually about, or why the conference had to be kept a secret (or how something like 23 different countries, and their associated delegates and security staff and so on, all managed to keep it hush-hush), I missed it. The villain wants to intercept the report — not steal it, not stop the conference, just learn what’s in it — which requires an elaborate plan with an impressionist and various decoys. Why not just honeytrap one of those 23 delegated? I guess that’d be too easy. What’s the villain’s motivation for wanting the report? No idea — he’s defined by being a reclusive pornography connoisseur, not by whatever he does to make money to afford his expensive porn habit.

Well, it’s all part of the film wanting to be like Bond, but not seeming to really understanding what makes the Bond films tick. On the bright side, it doesn’t take itself very seriously, which means it’s kooky fun in places (there’s a nice bit of farce in a hearse, for example). Not without entertainment value, then, but only hardened ’60s spy-fi fans need apply.

(1968)

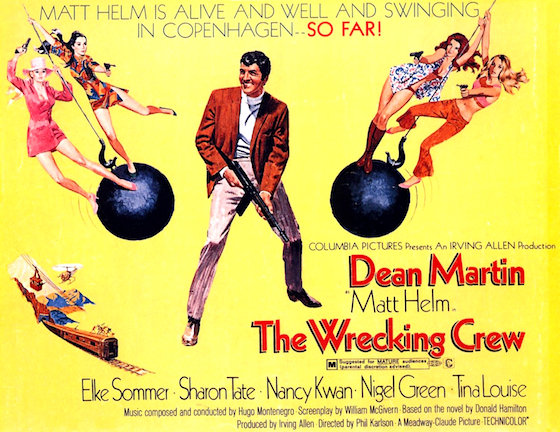

Phil Karlson | 101 mins | TV | 16:9 | USA / English | PG / PG

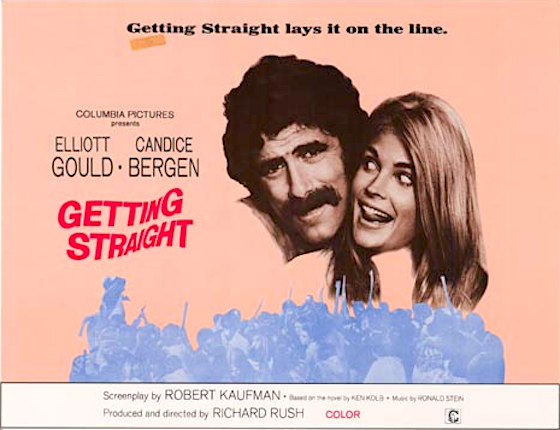

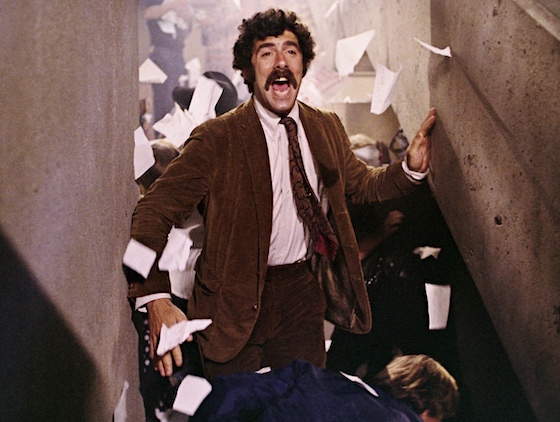

Unlike Hammerhead, I’m not sure anyone should apply to watch The Wrecking Crew, the last in a series of four movies starring the Rat Pack’s Dean Martin as Donald Hamilton’s Matt Helm. The character was a mite more successful than Charles Hood, then, but on screen and in his original literary form: the book series ultimately ran to 27 novels, the last published in 1993, with a 28th written but left unpublished after Hamilton’s death in 2006. The film series would’ve continued too — I guess not for that long, but for at least one more film. Reports vary on why a fifth instalment never happened, but one highly plausible version ties it to the murder of Sharon Tate. Tate co-stars in The Wrecking Crew and is quite the best thing about it. Martin loved working with her, and the plan was for her to return as Helm’s sidekick in the next film. But then what happened happened, and the followup was abandoned. (The alternate version is that poor reviews and poor box office for The Wrecking Crew just led the studio to scrap the series.) There are several tragedies about the murder of Sharon Tate, but I don’t think depriving us of more Matt Helm movies is one of them.

As for the lead character, Helm is a secret agent cum fashion photographer — and that’s not the only thing here that’ll remind you of Austin Powers. The Bond movies are often cited as the sole inspiration for Powers, but it was really drawn from across the ’60s spy-fi spectrum, and it’s clear Matt Helm was part of the mix. Unfortunately, The Wrecking Crew plays like a low-rent Austin Powers movie with any humour value sucked out. In his discussion around the film, Tarantino recalls seeing it in the cinema on its original release, and how audiences found it hilarious at the time. That wasn’t a quality I observed, personally. It’s clearly all tongue-in-cheek, but it rarely achieves levels of genuine amusement.

More tangible is the sensation that the film thinks it’s super cool and hip, but really isn’t. That might just be because of its lead. Dean Martin feels a bit like Roger Moore in his later Bond films: still behaving like he’s a young playboy while looking far too old for it. But even Moore, with his ageless class, felt more ‘with it’ than this. It really shows that the “effortless cool” of Bond does require some effort. The past-its-date feel is underscore (literally) by frequent random snippets of old-fashioned-sounding songs — presumably Dean Martin numbers, placed awkwardly to convey some of the hero’s thoughts (sample lyric: “If your sweetheart puts a pistol in her bed, you’d do better sleeping with your uncle Fred”). So much for the Swinging Sixties… and this was nearly 1970, too!

There’s no respite in the actual storyline, which is at least broadly followable (the villain has stolen $1 billion in gold, because who doesn’t want to be rich?), but then drowns itself in a flood of little logic problems and implausibilities, shortcomings of research or insight into foreign cultures, casual racism, lazy casting (why does someone called Count Massimo Contini sound like an English public schoolboy, other than because he’s the bad guy?), and no consideration for where surveillance cameras might actually be placed. You despair of constructively criticising the film for its mistakes — it’s beyond help.

The Wrecking Crew is another movie no doubt inspired by the desire to emulate the success of James Bond, but this is the kind of mediocre imitation that gives you a new appreciation for even the worst Bond movies. Hammerhead clearly struggled to compete due to the constraints of a tight budget, which it at least made up for somewhat with a vein of authentic Swinging Sixties antics. The Wrecking Crew, on the other hand, seems to have all the money it could need (it was produced by a major studio and had star names attached, remember), but nothing like enough charm or skill. It can’t even find benefit in fight choreography by the great Bruce Lee, with stunt performers incapable of convincing combat.

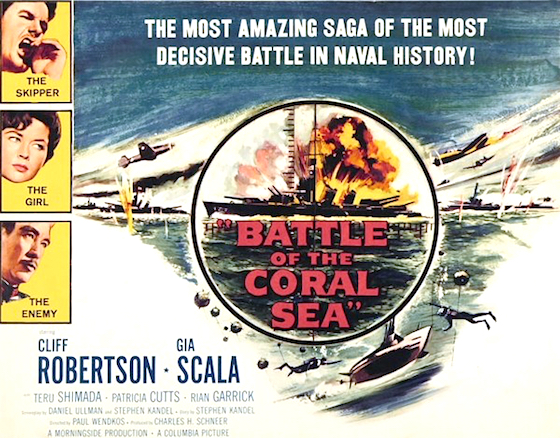

(1958)

Paul Wendkos | 83 mins | TV | 16:9 | USA / English | PG

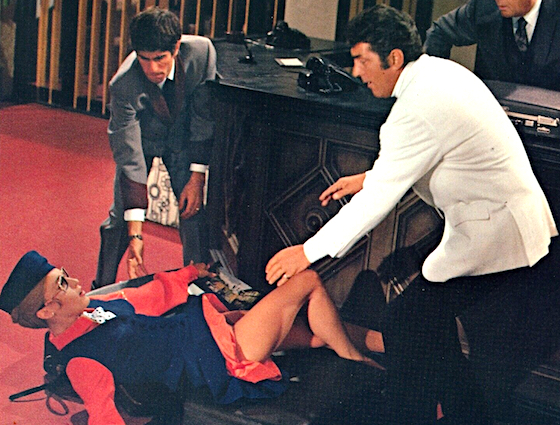

May, 1942, the South Pacific: a US submarine on a top-secret reconnaissance mission is captured by the Japanese fleet. Its crew are taken to remote island interrogation camp, where they just have to keep silent for a couple of days until what they know will no longer be of use to the enemy.

Yes, far from the combat movie the title implies, this middle-of-the-road World War 2 movie is one part submarine adventure (the first act) to two parts POW thriller (the rest). The latter also includes an action-packed escape for the climax, which is almost a moderately exciting action sequence, but is marred by a litany of minor daft decisions. For example: the escapees start by killing a couple of guards, but only pick up one of their guns; then they use that gun to mow down more guards, but still don’t bother to grab any more weapons. When some of them get killed a minute or two later, you can’t help but feel it was their own damn fault.

It picks up some points for making the camp’s commander a reasonable man — a human being, rather than an alien, vicious, evil torturer, which is the stereotype of Japanese WW2 prison camps. That said, considering how infamously brutal said camps were/could be, the niceness of the prisoners’ treatment makes the film feel somewhat neutered. It’s not like the captured seamen get to laze around all day — they’re put to work — but you feel like these guys aren’t really suffering, not compared to what others went through. It contributes to the feeling of the film being a something-or-nothing tale; just another story of the war, rather than an exceptionally compelling narrative.

Apparently the eponymous battle was rather important, though: a voice over informs us that “it was the greatest naval engagement in history”… before adding that “the victory laid the groundwork for the even greater sea victory at Midway.” So it was the greatest… except the next one was greater? Who wrote this screenplay, Donald Trump? We do actually get to see the battle, eventually, when it turns up as an epilogue, conveyed via a speedy stock-footage-filled montage. I wonder how much of that was fed into the trailer…

Battle of the Coral Sea is the kind of film I would’ve completely overlooked if Quentin Tarantino hadn’t included it in his Swinging Sixties Movie Marathon (it represents the kind of thing Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s Rick Dalton would’ve appeared in early in his career, as one of the seamen with a couple of lines), and I don’t feel I’d’ve really missed anything. It’s not a poor film — anyone with a fondness for ’50s-style war movies will find something to enjoy in it — but it’s not a noteworthy one either.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is in cinemas now.