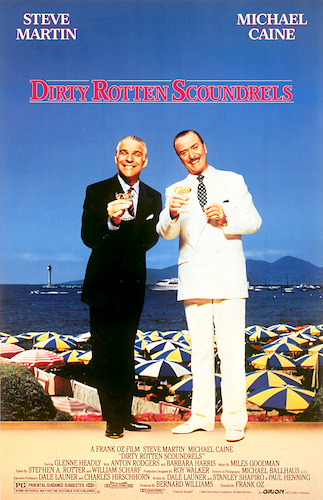

Right, let’s try (again) to get things back on track.

These compilations were/are meant to keep my reviewing roughly up-to-date with my viewing, but I don’t think stuffing them with too many films at once is the right way to go. I don’t know about anyone else, but I feel like five or six per post is about right (with some leeway, of course — I’m sure four or seven would be fine too). However, dividing like that means getting out of sync with Real Life, so I suppose I should clarify when “weeks 9–11” were: Monday February 28th to Sunday 20th March, to be precise. And back then, I watched…

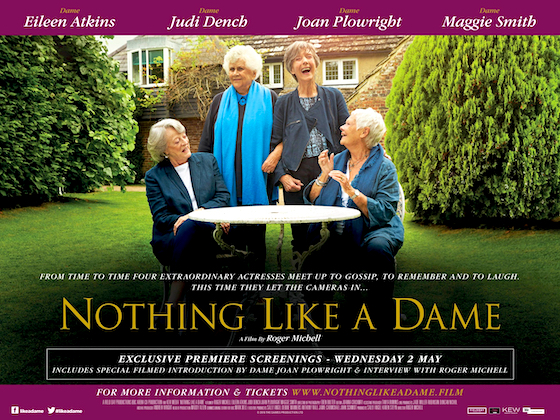

Nothing Like a Dame (2018)

Tintin and the Temple of the Sun

(1969)

aka Tintin et le temple du soleil / The Adventures of Tintin: The Prisoners of the Sun

Eddie Lateste* | 75 mins | DVD | 4:3 | Belgium & France / English | U

This fourth big-screen outing for the Belgian reporter also continues the popular TV series, Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin, made by Belgian studio Belvision from 1957 to 1962. Having adapted ten of Hergé’s volumes for TV, here they tackled two more: two-parter The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun. The story sees Tintin and chums head to Peru on the trail of their kidnapped friend, Professor Calculus, and to investigate an Incan curse that has befallen a previous party of archaeologists.

Trekking up mountains and through jungles, with nefarious agents in pursuit, plus all the to-do with ancient curses and whatnot, this is chock-a-block with good old “Boy’s Own Adventure” stuff. As with so many of those, the joy lies in being swept along with the adventure rather than thinking about it too hard (our heroes are saved at the end because the Captain happens to have a scrap of newspaper that Snowy happens to steal that Tintin happens to fancy having a look at that happens to mention a handy forthcoming event). By the same token, there’s also the unavoidable effects of time: some of it feels a teensy bit racist nowadays; Tintin makes his way through the jungle merrily murdering animals left, right and centre. The animation itself is fine, with designs and an overall visual style that emulate Hergé well, but it does have a certain TV-ness.

It’s also not available in the greatest of copies, at least to English-language viewers. Reportedly the original version contains two songs, both of which were cut from the UK video release, but only one of which has been restored for the DVD (and, I presume, the version currently available to stream from Apple, etc). Although most of the film is dubbed, the song is in the original French, unsubtitled; and has clearly been edited, because there are digital freeze frames around it. At the start of the film, the title card has been replaced in a similarly awkward fashion. Then there’s the 5.1 remix, which seems to be missing some effects and music cues. You can still enjoy the majority of the film despite these distractions, but it’s disappointing that we still have to put up with such palaver nowadays.

Tintin and the Temple of the Sun is the 19th film in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2022.

* Many (but not all) online sources list Lateste as the director, including IMDb, but the film itself doesn’t actually credit him — the only director-like credit is for “Belvision”. Lateste is credited as one of the screenwriters, at least. ^

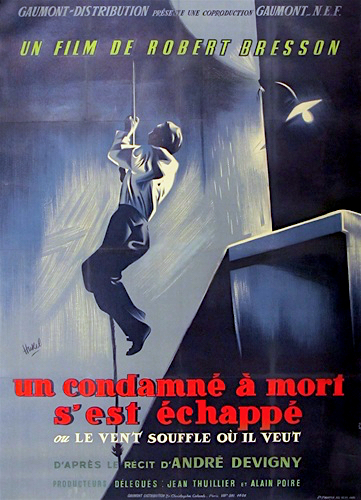

Los Olvidados

(1950)

aka The Young and the Damned

Luis Buñuel | 81 mins | digital (HD) | 1.37:1 | Mexico / Spanish | 12

Combine the literal translation of the film’s title — The Forgotten Ones — with the US retitling — The Young and the Damned — and you build a sense of what Los Olvidados (as it’s been released in the UK) is about. To be clearly, it’s a socially-realist depiction of life for children in the slums of Mexico City. Although initially condemned (according to IMDb, it only played for three days in Mexico before the “enraged reactions” of the press, government, and upper- and middle-class audiences caused it to be pulled), it’s since been reevaluated as one of the greats of Latin American cinema. Certainly, watching it after films like The 400 Blows (made almost a decade later), City of God (over 50 years later), and Capernaum (almost 70 years later), its influence is felt.

The downside to that is the film feels somewhat less fresh and more worthy than the later efforts. It’s got an overt anti-poverty message that is admirable but sometimes heavy-handed (a school principal character feels like he’s been inserted just to state the film’s thesis out loud) or naïvely optimistic (the opening voiceover asserts that child poverty will ultimately be solved by progress. Over 70 years later, I don’t think progress is doing a great job…) While much of the movie works at its intended goal, when aspects like these intrude it stops feeling like a realistic depiction of poverty and more like a straightforward polemic about how it should be fixed. On the bright side, it avoids the lure of a pat happy ending — although one was actually discovered in 2002, apparently shot to appease Mexican censors. Clearly they managed to get the film released without having to cave on that point, and it’s better for it.

Los Olvidados is the 20th film in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2022. It was viewed as part of Blindspot 2022.

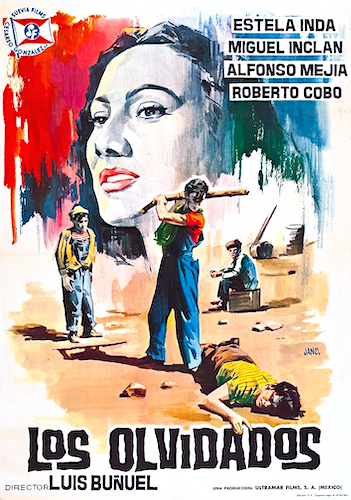

The Very Excellent Mr. Dundee

(2020)

Dean Murphy | 88 mins | digital (HD) | 2.35:1 | Australia & USA / English | 12 / PG-13

Not a fourth Crocodile Dundee film, but rather a depiction of the accidentally-chaotic life of that series’ leading man, Paul Hogan, the archetypal Aussie now living in LA and, reaching his 80s, somewhat bemused by the modern world.

Even from that quick summary, you can tell it’s not a terribly original premise. Couple that with a clearly small budget and you have a recipe for many dismissing the film out of hand. Personally, I found it to be surprisingly enjoyable, in a laidback, undemanding way. None of it is properly hilarious (though a bizarre musical sequence comes close), but it’s kinda amiable, and almost heartwarming at the end. Discerning viewers should perhaps not apply, but if you have any affection for the second or third Crocodile Dundee films (again, widely maligned instalments that I found passably entertaining), this is worth a punt.

The King’s Man

(2021)

Matthew Vaughn | 131 mins | Blu-ray (UHD) | 2.39:1 | UK & USA / English | 15 / R

Co-writer/director Matthew Vaughn expands the Kingsman universe with this World War I-era prequel that delves into the backstory of how the eponymous organisation was founded. Unlike so many prequels, this does feel like a story worth telling — we don’t necessarily need it, but it’s not merely an exercise in visualising events we’ve already been told, or coming up with over-elaborate reasons for people’s names or whatever (why couldn’t Han Solo’s birth name have just been Han Solo, hm?)

The story begins with Europe on the brink of war, and our heroes — led by the Duke of Oxford (Ralph Fiennes) — attempting to stop it. History tells us they fail, and so the narrative unfurls across WWI as they try to bring it to a close. That will see them come up against the manipulations of Rasputin (Rhys Ifans), who’s part of a secret organisation plotting to bring down the great empires.

Let’s cut to the chase: the Kingsman films have a rep for elaborate fight scenes set to pop music. One of the major villains is Rasputin. You only need a passing familiarity with the disco hits of the ’70s to know what I was looking forward to here. Well, it doesn’t happen. Indeed, that stylistic calling card is more or less entirely abandoned (the fight does happen, of course, but it’s set to Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture — kind of like era-appropriate ‘pop’ music, I guess?) Apparently Vaughn did originally intend the sequence to be set to an orchestral version of the song in question, but ultimately felt it didn’t work.

This, perhaps, speaks to another concern I had going in, which was that Kingsman’s highly irreverent, almost satirical tone might clash with the all-too-real WWI setting. Such an historical tragedy doesn’t feel right to be made light of in that way, even over a century later. So, as if to compensate, Vaughn and co have toned down the humour, making The King’s Man fairly serious… but without fully sacrificing the near-whimsy at other times, because, well, it’s part of the franchise. The result is a little awkward, tonally, swinging back and forth between historical seriousness and franchise-establishing fun. Put another way, it’s hamstrung by being an entry in a series known for its irreverence that feels the need to show due reverence to WWI. That’s a clash of values it struggles with, some might say admirably, but can’t quite reconcile. In short, it’s too serious to be a Kingsman film, but too Kingsman-y to be a standalone WWI-set action-adventure.

I wouldn’t say it’s a disaster, by any means — but then, I enjoyed The Golden Circle when many lambasted it, so make of that what you will. Nonetheless, I’m looking forward to the next film getting back to Eggsy & co in the present day.

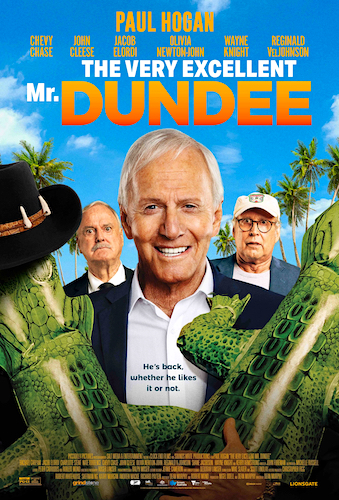

Dirty Rotten Scoundrels

(1988)

Frank Oz | 110 mins | digital (HD) | 1.85:1 | USA / English | PG / PG

Michael Caine and Steve Martin star as a couple of chalk-and-cheese con men, pilfering the fortunes of wealthy single ladies on the French Riviera, in this fun con caper with a neat sting in its tail.

Caine hits just the right note as a charming con artist, his manner inspired by David Niven, who played the role in the original, 1964’s Bedtime Story. I was unaware the film was a remake until after watching it, though I did know it was itself subject to a gender-bent do-over in 2019, The Hustle. I don’t know how similar Bedtime Story and Dirty Rotten Scoundrels are, but, based on its trailer, The Hustle seems to be a direct lift from this, albeit peppered with the kind of pratfalling that’s de rigueur in modern big screen comedy.

Marlon Brando was Niven’s co-lead, whereas here Caine gets Steve Martin as the very embodiment of a brash American — a little too brash, if anything, though reportedly there were bits he actually reined in. The running time could have done with a similar consideration, because it’s a little long for its breezy premise and tone (running 110 minutes, it would be better nearer 90), but that’s a minor complaint — it rarely feels too slow or draggy, just a little long overall.

Dirty Rotten Scoundrels is the 21st film in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2022.

Nothing Like a Dame

(2018)

aka Tea with the Dames

Roger Michell | 77 mins | digital (HD) | 16:9 | UK / English | 12

Four thespian friends, Dames all — Eileen Atkins, Judi Dench, Joan Plowright, and Maggie Smith — gather for a natter about their careers and lives. That’s it, that’s the film.

Given the setup, plus the style of advertising and US retitle, you’d be forgiven for expecting a gentle bit of fluff; eavesdropping on a pleasant chinwag with four venerable British actresses. The film is that, in places, but it also has a surprising undercurrent of sadness running throughout, as these ageing ladies reflect on the ups and downs of their careers and personal lives now that they’re (shall we say) closer to the end than the beginning. It rarely bubbles to the surface, but it always feels like it’s there, somehow inescapable.

If that gives proceedings more texture than you might’ve expected, then the film’s biggest flaw lies elsewhere. For me, it’s that it wasn’t long enough. The conversations are often delightful and occasionally insightful, but you feel like there’s so much more to be gleaned from these women. The film chops about between topics and pairings, always feeling like we’re getting snippets of the full conversation, never the true depth; like we’re watching a highlights reel of what should be a three-hour series, or something like that. I know it’s an old theatrical adage to “leave ’em wanting more”, but I really did want some more.