I have a backlog of 437 unreviewed feature films from my 2018 to 2021 viewing. This is where I give those films their day, five at a time, selected by a random number generator.

Today, everything from silent comedies to afterlife comedies to toy-licence-based adventure comedies (a burgeoning genre we’re sure to see more of in years to come). Plus a revisionist Arthurian legend for good measure.

This week’s Archive 5 are…

Guinevere

(1994)

Jud Taylor | 91 mins | digital (SD) | 4:3 | USA & Lithuania / English

This Lifetime TV movie is like an American Renaissance faire cosplay version of Arthurian legend. Its attempt at a feminist take on the famed stories is interesting, but deserves better writing, filmmaking, and accents.

Most of Guinevere’s flaws come from its low-rent made-for-US-TV-in-the-’90s roots (the mediocre direction; the tacky music score), but that’s also its biggest asset, because when and for whom it was made means it was shot on film, which gives it a certain gloss (even when downgraded to SD) that taped or digital productions simply lack.

Story-wise, the love triangle stuff from legend is there, but given a YA spin — it’s practically Arthurian Twilight. Are you Team Arthur or Team Jacob? The feminist bent is not subtle either, which, given changes in attitudes over the past few decades, makes you wonder if it’s ripe for a re-adaptation (it’s based on a trilogy of novels with magnificently florid titles like Child of the Northern Spring and Queen of the Summer Stars).

You see, despite everything, I didn’t hate it. Maybe I should — it’s not good, by any means — but I liked what it was trying to do, even while it didn’t do it well (at all). It’s a concept someone should definitely take another run at.

Guinevere was #209 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2020.

The Kid

(1921/1972)

Charlie Chaplin | 50 mins | DVD | 4:3 | USA / silent | U

Charlie Chaplin’s first feature-length work as star and director sees his Tramp character caring for an abandoned child (Jackie Coogan). I say “feature length”, but when you combine a re-edit Chaplin performed in 1972 with PAL speedup, it runs just 50 minutes. I’ve gotta say, I appreciated that. I’ve felt some of Chaplin’s other films have gone on a bit, whereas this didn’t outstay its welcome. That said, I did feel the Dreamland sequence near the end was filler. That aside, it’s quite a nice film. Coogan is particularly effective — he has just the right look for the role, and was obviously very good at imitation and/or taking direction.

Regarding the length, the original 1921 release was 68 minutes, but for a 1972 reissue Chaplin cut some footage, appears to have sped up the frame rate of the rest, and added a score and some sound effects too. It’s only this cut that gets released on disc nowadays (often with the excised footage included as deleted scenes). The original cut clearly still exists, and yet everyone just seems to overlook it — it’s only if you bother to read up on the film that you discover what most people are watching and reviewing as “a 1921 film” is actually a 50-years-later director’s cut. Imagine if we all just ignored, say, Blade Runner’s original version and just treated The Final Cut as— oh, wait. Never mind.

The Kid was #60 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2020.

Defending Your Life

(1991)

Albert Brooks | 111 mins | Blu-ray | 1.85:1 | USA / English | PG / PG

Writer-director Albert Brooks stars as a loner advertising exec who dies and finds himself in a bureaucratic afterlife where he has to prove that he overcame his fears. While he awaits his trial, he finally meets the love of his (after)life, Julia (Meryl Streep).

For a film that’s literally about life and death, Defending Your Life is rather gentle. Like, it’s rarely laugh-out-loud funny, but it’s often slightly amusing. And it’s unhurried, too: its 111 minutes aren’t tedious by any means, but it doesn’t rush anywhere. A fun side effect of this is how casual its world-building is. This is a very specific vision of the afterlife, an entire world with its own rules, and while that’s all explained, it’s not laid out in minute detail like a how-to guide. I feel like this is something movies used to happily do but has been eroded by the need for everything to be over-explained and -analysed.

I liked Defending Your Life a good deal (I’ve picked up a couple more of Brooks’s films on Blu-ray off the back of it), and part of that is certainly its laidback style. Nonetheless, perhaps if it were snappier — quicker witted and paced — it might be a better-remembered film, comparable to something roughly contemporaneous like Groundhog Day.

Defending Your Life was #113 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2021.

The LEGO Movie 2:

The Second Part

(2019)

Mike Mitchell | 107 mins | Blu-ray (3D) | 2.40:1 | USA, Denmark, Norway & Australia / English | U / PG

After the surprise success of The LEGO Movie, naturally a sequel had to follow. Unfortunately, it’s altogether less surprising, because it’s that old fashioned sequel thing: a less-good do-over of the first movie.

The Second Part feels less focused than its predecessor. It still has a positive message (about not needing to grow up, and about playing together, or something), but it takes a while to get to it, rather than baking it into the entire experience. Maybe that’s intellectualising things a bit — this is a family-friendly adventure-comedy starring toys, after all. But still, the overall journey doesn’t feel as exciting or fun. There are fun little bits on the way, but, moment to moment, it lacks the spark of the first one.

For a specific example, take the breakout hit of the first film, the irritating song Everything Is Awesome. That angle has been doubled down on, with multiple attempts at emulating the “irritating but kinda loveable” song formula; but while these numbers are annoying while they last, they don’t have the irrepressible catchiness of the first film’s signature achievement — a mixed blessing, to be sure (at least they won’t be stuck in your head afterwards). The end credits are accompanied by a song that jokes about the credits being the best part… but, in this case, the credits kinda are the best part.

The LEGO Movie 2: The Second Part was #33 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2020.

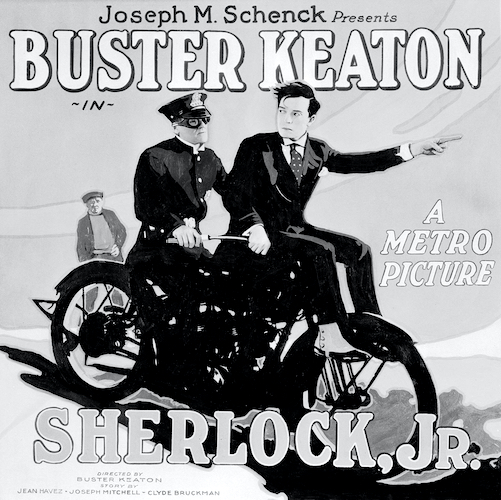

Sherlock Jr.

(1924)

Buster Keaton | 45 mins | Blu-ray | 1.33:1 | USA / silent | U

Apparently there are ever-raging arguments within the silent film fan community about who was the best comedian of the era. Charlie Chaplin’s got the most widespread recognition, but Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd have their advocates, of course, and I guess there are probably people shouting in favour of smaller names too. I didn’t think I’d ever pick a ‘side’ in these debates — I’m certainly not about to go seeking them out and wading in — and, fundamentally, I do hold with the notion that the greats are all great and so why not appreciate them all? — but, from what I’ve seen thus far, I’m finding Keaton’s work more consistently enjoyable than Chaplin’s. Sherlock Jr. is my favourite of his that I’ve seen so far.

Keaton plays a film projectionist who’s studying to be a detective on the side. When he’s framed for the theft of a watch, his apparent guilt doesn’t give him much chance to put his skills to the test. But when he falls asleep during a movie, he steps inside it and becomes the world’s greatest detective. And when I say “steps inside”, I mean it in the most literal sense possible: the projectionist walks through the screen and into the movie, and is suddenly subject to its whims — for example, he’s confounded whenever it cuts to a new location. The sequence is both thoroughly entertaining and technically faultless — and I say that viewing it nearly 100 years after it was made, after all the advances in technique and effects we’ve had in that time. Reportedly, the film’s cameraman, Byron Houck, went as far as using surveying equipment to ensure the camera was positioned correctly so the transitions were seamless. The effort paid off.

The same is true in several other incredible sequences, like a billiards game filled with trick shots, which Keaton rehearsed for four months with a pool expert and then took five days to film. Or a motorbike chase with more I-can’t-believe-he-just-did-that death-defying stunts than one of Tom Cruise’s impossible missions. The technical skill is faultless and, even if you’re not wowed by how they pulled it off, the sequences are immensely entertaining in their own right. Maybe it’s just personal taste, but this is why I have a preference for Keaton: his skits are more ingenious, better paced, and backed up with impressive stunt work. When you mix those daredevil antics with genuine movie magic, as he does here, you get a majestic, unforgettable farce.

Sherlock Jr. was #102 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2019. It was viewed as part of What Do You Mean You Haven’t Seen…? 2019. It placed 3rd on my list of The Best Films I Saw in 2019.