It’s Day 2 of the AMPLIFY! film festival (new content goes live at 1am, FYI). Among today’s additions is the UK premiere of The Mole Agent — one of 18 UK premieres that are part of the festival.

My review of that in a moment, but first, also debuting today are…

- Manhattan Project-related biopic Adventures of a Mathematician

- mother-daughter drama Asia

- celebration of analogue tech An Impossible Project

- plus 2 live Q&As, attached to Adventures of a Mathematician and Rose Plays Julie.

Incidentally, I’d recommend Rose Plays Julie, an engrossing and powerful psychological thriller (I’ll review it in full soon, time permitting).

(2020)

Maite Alberdi | 90 mins | digital (HD) | 1.85:1 | Chile, USA, Germany, Netherlands & Spain / Spanish

It’s easy to make The Mole Agent sound like the setup for a comedy: it’s about a doddery 83-year-old who must learn to be a spy. And, indeed, there are scene where the film is very amusing; particularly early on, when the octogenarian in question, Sergio Chamy, struggles to get to grips with the technology he’ll need to use, much to the exasperation of his spymaster, Rómulo Aitken.

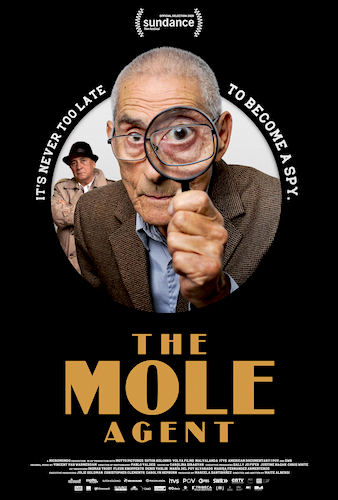

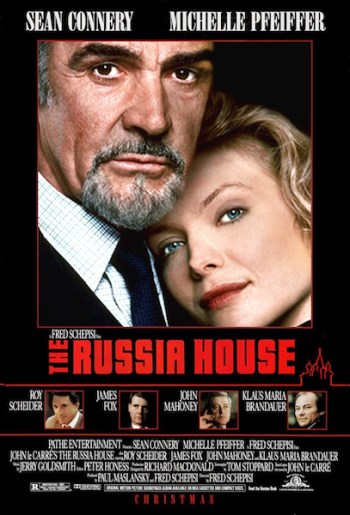

Except that premise, which the film has leant its promotion on (note the tagline on the above poster: “it’s never too late to become a spy”), is slightly misleading. Aitken isn’t a spymaster, he’s a private detective, who’s been hired to investigate allegations of abuse at an old people’s home — hence the need for an old person to go in as an undercover observer. It’s not exactly Bond, or even Le Carré, is it?

Indeed, director Maite Alberdi leans into a different genre — film noir — shooting the early briefing scenes with a heavy use of venetian blinds, either peering through them or employing their distinctive shadows. It’s a level of visual panache you’re not used to from a conventional documentary. It might lead you to question if what you’re watching was entirely documentary in nature, were it not for the fact that these scenes take place in the ‘safety’ of the PI’s office —it’s not unreasonable to assume the film crew semi-staged a couple of ‘scenes’ to add a bit of visual interest. (They clearly did it for the promo photos, too. I mean, just look at this one…)

The real questions of form begin to emerge once Sergio begins his undercover mission. To be able to film what he’s up to, the documentary crew have inveigled themselves into the same old people’s home with the cover story that they want to make a film about a new resident — so when Sergio turns up, what a perfect coincidence, and excuse to focus their filming on him. Except… if this care home is abusing its residents, are they going to continue doing that with a film crew present? Heck, surely they wouldn’t even agree to a film being made at all?

Well, the whole investigative goal goes out the window pretty quickly, anyway. Sergio is initially diligent about snooping around and secretly recording his reports for Rómulo, but he soon begins to make friends and become involved in the life of this little community. The other residents become his friends, and he’s more invested in their wellbeing as their comrade than as an outside observer. Concurrently, the film becomes less interested in the comedic fumbles of an octogenarian secret agent, and more in exploring the lives of these old people. Sergio’s fellow residents aren’t faceless possible-victims, but characters we get to know too.

What Sergio ultimately finds (spoilers!) is neglect — not by the staff, but by the families that shoved their elders away and forgot about them. For the film, that’s a much bigger observation; one on the state of society as a whole, rather than the misdeeds of a single care home. (If anything, the home is wholly vindicated, because we see how much they care for and support their residents.)

If The Mole Agent has a fault it’s that it can be a little slow at times — though, given the pace these (often delightful) oldies move at, perhaps that was unavoidable. But it’s worth the investment nonetheless, because it’s ultimately a powerfully affecting experience. It’s a film that intrigues you with its laughable premise, then swings round to punch you in the emotions with a crystal-clear message.

The UK premiere screening of The Mole Agent is on AMPLIFY! until Friday 13th November. It’s on general release in the UK from 11th December.

Disclosure: I’m working for AMPLIFY! as part of FilmBath. However, all opinions are my own, and I benefit in no way (financial or otherwise) from you following the links in this post or making purchases.

The cinema was blessed — or, depending on your point of view, blighted — by an abundance of espionage-related movies last year (see: the intro to

The cinema was blessed — or, depending on your point of view, blighted — by an abundance of espionage-related movies last year (see: the intro to  that usually just means an overabundance of the F-word. Here we have at least one clear headshot, a dissolving throat, a knife through a hand, and more photos of a henchman’s penis than you ever needed to see. (That last one’s only describable as “gruesome” depending on your personal predilections, of course.)

that usually just means an overabundance of the F-word. Here we have at least one clear headshot, a dissolving throat, a knife through a hand, and more photos of a henchman’s penis than you ever needed to see. (That last one’s only describable as “gruesome” depending on your personal predilections, of course.) The extended (aka unrated) cut contains almost 10 minutes of extra material, detailed

The extended (aka unrated) cut contains almost 10 minutes of extra material, detailed

Favourite Film of the Month

Favourite Film of the Month

Steven Spielberg’s true-story Cold War drama stars Tom Hanks as insurance lawyer James B. Donovan, who is tapped to defend captured Soviet spy Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance). After Donovan insists on doing his job properly, he manages to spare Abel the death penalty — which comes in handy when the Soviets capture spy-plane pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell) and a prisoner exchange is suggested, which the Russians want Donovan to negotiate.

Steven Spielberg’s true-story Cold War drama stars Tom Hanks as insurance lawyer James B. Donovan, who is tapped to defend captured Soviet spy Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance). After Donovan insists on doing his job properly, he manages to spare Abel the death penalty — which comes in handy when the Soviets capture spy-plane pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell) and a prisoner exchange is suggested, which the Russians want Donovan to negotiate. If we’re talking storytelling oddities, another is the manner in which Powers’ backstory is integrated. As Donovan continues to defend Abel, the film suddenly becomes subjected to scattered interjections, in which we see pilots being selected and then trained to fly secret reconnaissance missions in a new kind of plane. Any viewer who has read the blurb will know where this is going, but it’s so disconnected to the rest of the narrative that it felt misplaced, at least to me. The same is true when we suddenly meet Frederic Pryor (Will Rogers), an American student in Berlin who’s mistaken for a spy and arrested by the East. It turns out we need to know about him because Donovan attempts to use his negotiations to get a two-for-one deal, exchanging Abel for both Powers and Pryor. Knowing the stories of the men Donovan will be negotiating for is not a bad point, but I can’t help but feel there was a smoother way to integrate them into the film’s overall narrative.

If we’re talking storytelling oddities, another is the manner in which Powers’ backstory is integrated. As Donovan continues to defend Abel, the film suddenly becomes subjected to scattered interjections, in which we see pilots being selected and then trained to fly secret reconnaissance missions in a new kind of plane. Any viewer who has read the blurb will know where this is going, but it’s so disconnected to the rest of the narrative that it felt misplaced, at least to me. The same is true when we suddenly meet Frederic Pryor (Will Rogers), an American student in Berlin who’s mistaken for a spy and arrested by the East. It turns out we need to know about him because Donovan attempts to use his negotiations to get a two-for-one deal, exchanging Abel for both Powers and Pryor. Knowing the stories of the men Donovan will be negotiating for is not a bad point, but I can’t help but feel there was a smoother way to integrate them into the film’s overall narrative. hints at emotions under the surface rather than declaiming them. A lesser film would’ve made a point of this — would’ve had Hanks’ lawyer struggling to understand and relate to his client’s low-key nature — but, instead, Donovan is a man who can identify with this mode of being, at least to an extent. There’s a reason they talk a couple of times about the ‘stoikiy muzhik’.

hints at emotions under the surface rather than declaiming them. A lesser film would’ve made a point of this — would’ve had Hanks’ lawyer struggling to understand and relate to his client’s low-key nature — but, instead, Donovan is a man who can identify with this mode of being, at least to an extent. There’s a reason they talk a couple of times about the ‘stoikiy muzhik’. allows the whole film to be equally as subtle, even as it remains gripping and entertaining. However, the storytelling quirks are a mixed success, the pace they sometimes lend offset by the almost non sequitur style of the captured Americans’ backstories. Nonetheless, this is a classy but still enjoyable dramatic thriller, which takes a seat among Spielberg’s better works.

allows the whole film to be equally as subtle, even as it remains gripping and entertaining. However, the storytelling quirks are a mixed success, the pace they sometimes lend offset by the almost non sequitur style of the captured Americans’ backstories. Nonetheless, this is a classy but still enjoyable dramatic thriller, which takes a seat among Spielberg’s better works. The BBC’s long-running spy thriller series

The BBC’s long-running spy thriller series  Early seasons focused at least as much on things like the mundanity of spycraft, or how one went about having a personal life while also being a sometimes-undercover agent, as they did on the exciting action of counterespionage — as evoked in the memorable tagline “MI5 not 9 to 5”, of course. As the years rolled on, things got increasingly outlandish and grandiose, just as almost every spy series that starts out “grounded” is wont to do. In season three, an entire episode was spent on the moral dilemma of whether it was acceptable to assassinate someone; a couple of years later, assassinations would just be a halfway-through-an-episode plot development. The one constant through all this was section chief Harry Pearce (Peter Firth), the M figure to a rotating roster of “James Bond”s, including Matthew “

Early seasons focused at least as much on things like the mundanity of spycraft, or how one went about having a personal life while also being a sometimes-undercover agent, as they did on the exciting action of counterespionage — as evoked in the memorable tagline “MI5 not 9 to 5”, of course. As the years rolled on, things got increasingly outlandish and grandiose, just as almost every spy series that starts out “grounded” is wont to do. In season three, an entire episode was spent on the moral dilemma of whether it was acceptable to assassinate someone; a couple of years later, assassinations would just be a halfway-through-an-episode plot development. The one constant through all this was section chief Harry Pearce (Peter Firth), the M figure to a rotating roster of “James Bond”s, including Matthew “ But I’m getting ahead of myself. The story begins with Harry running an op that goes wrong, during which terrorist Adam Qasim (Elyes Gabel) is sprung from custody just before being handed over to the CIA. Cue international incident. Naturally the blame is pinned on Harry, who consequently throws himself off a bridge. Except no one buys that, so they drag in Will Holloway (Kit Harington), a disenchanted one-time protégé of Harry’s (i.e. the series’ latest “younger man who can do the running around”). He knows nothing about it (

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The story begins with Harry running an op that goes wrong, during which terrorist Adam Qasim (Elyes Gabel) is sprung from custody just before being handed over to the CIA. Cue international incident. Naturally the blame is pinned on Harry, who consequently throws himself off a bridge. Except no one buys that, so they drag in Will Holloway (Kit Harington), a disenchanted one-time protégé of Harry’s (i.e. the series’ latest “younger man who can do the running around”). He knows nothing about it ( The trailers attempt to promise some of that kind of action, but they’re a bit of a cheat: what adrenaline the film has is mostly released in tiny bursts, scattered throughout. That strategy is fine if you’ve got the money to make each little burst a solid sequence, but when the entirety of some sequences is “jumping through a window” or “climbing a wall to get into a flat”, well… Sure, it looks good in the trailer — it promises lots of action in different places at different times — but that’s also a promise the movie can’t fulfil. The Greater Good certainly isn’t just a low-rent action movie — it’s driven by its plot — but if they’d saved up the filmmaking time, effort, and expense afforded to those single-dose action moments and poured it all into one sequence (in addition to the two or three fully-realised action sequences that the film does have), it might’ve paid dividends.

The trailers attempt to promise some of that kind of action, but they’re a bit of a cheat: what adrenaline the film has is mostly released in tiny bursts, scattered throughout. That strategy is fine if you’ve got the money to make each little burst a solid sequence, but when the entirety of some sequences is “jumping through a window” or “climbing a wall to get into a flat”, well… Sure, it looks good in the trailer — it promises lots of action in different places at different times — but that’s also a promise the movie can’t fulfil. The Greater Good certainly isn’t just a low-rent action movie — it’s driven by its plot — but if they’d saved up the filmmaking time, effort, and expense afforded to those single-dose action moments and poured it all into one sequence (in addition to the two or three fully-realised action sequences that the film does have), it might’ve paid dividends.

If you’re versed in sci-fi/fantasy cinema, you’ve heard of Scanners even if you haven’t seen it: it’s the one with the (in)famous exploding head. That moment is distinctly less shocking for those of us coming to the film as a new viewer at this point: gore perpetuates genre cinema nowadays, so it’s less striking,

If you’re versed in sci-fi/fantasy cinema, you’ve heard of Scanners even if you haven’t seen it: it’s the one with the (in)famous exploding head. That moment is distinctly less shocking for those of us coming to the film as a new viewer at this point: gore perpetuates genre cinema nowadays, so it’s less striking, emotional journey or something is the core of the film. As if to make up for it, McGoohan is of course excellent, acting everyone else off the screen, while Ironside makes for an excellent villain, naturally. Some say that the final psychic battle, between Lack and Ironside, is underwhelming, but I thought it was excellently realised, a tense and effective struggle. Such brilliant effects and sequences are scattered throughout the film.

emotional journey or something is the core of the film. As if to make up for it, McGoohan is of course excellent, acting everyone else off the screen, while Ironside makes for an excellent villain, naturally. Some say that the final psychic battle, between Lack and Ironside, is underwhelming, but I thought it was excellently realised, a tense and effective struggle. Such brilliant effects and sequences are scattered throughout the film. The team behind

The team behind  An even bigger part of the film’s triumph, and what likely led it to over $400 million worldwide in spite of its higher-than-PG-13 classifications (it’s Vaughn’s highest-grossing film to date, incidentally; even more so than

An even bigger part of the film’s triumph, and what likely led it to over $400 million worldwide in spite of its higher-than-PG-13 classifications (it’s Vaughn’s highest-grossing film to date, incidentally; even more so than  rather than the supposed real-world universe of spy movies. What the worldwide success of Kingsman proves is that audiences don’t need the set-dressing of superpowers to accept an action movie that’s less than deadly serious. It’s a place I don’t think the Bond movies could go anymore — not without accusations of returning to the disliked Moore or late-Brosnan films — but it’s one many people clearly like, and Kingsman fulfils it.

rather than the supposed real-world universe of spy movies. What the worldwide success of Kingsman proves is that audiences don’t need the set-dressing of superpowers to accept an action movie that’s less than deadly serious. It’s a place I don’t think the Bond movies could go anymore — not without accusations of returning to the disliked Moore or late-Brosnan films — but it’s one many people clearly like, and Kingsman fulfils it. Criticisms of the film tend to pan out to nought, in my opinion. Is there too much violence? There’s a lot, certainly, but part of the point of that church sequence (for instance) is just how long it goes on. Other excellent action sequences (the pub fight you might’ve seen in clips; the car chase in reverse gear; the skydiving) aren’t predicated on killing. Similarly, Samuel L. Jackson’s baseball-capped lisping billionaire is a perfect modern riff on the traditional Bond villain, not some kind of attack on Americans or people with speech impediments. Some have even attempted a political reading of the film, arguing it’s fundamentally conservative and right-wing because the villain is an environmentalist. Again, I don’t think the film really supports such an interpretation. In fact, I think it’s completely apolitical — just like its titular organisation, in fact — and such perspectives are being entirely read into it by the kind of people who read too much of this kind of thing into everything.

Criticisms of the film tend to pan out to nought, in my opinion. Is there too much violence? There’s a lot, certainly, but part of the point of that church sequence (for instance) is just how long it goes on. Other excellent action sequences (the pub fight you might’ve seen in clips; the car chase in reverse gear; the skydiving) aren’t predicated on killing. Similarly, Samuel L. Jackson’s baseball-capped lisping billionaire is a perfect modern riff on the traditional Bond villain, not some kind of attack on Americans or people with speech impediments. Some have even attempted a political reading of the film, arguing it’s fundamentally conservative and right-wing because the villain is an environmentalist. Again, I don’t think the film really supports such an interpretation. In fact, I think it’s completely apolitical — just like its titular organisation, in fact — and such perspectives are being entirely read into it by the kind of people who read too much of this kind of thing into everything. Not everything hinges on being wall-to-wall groundbreaking, though, and Kingsman has so much to recommend it. It ticks all the requisite boxes of being exciting and funny, and some of its sequences are executed breathtakingly. The plot may move along familiar tracks — deliberately so — but it pulls out a few mysteries and surprises along the way. There’s an array of likeable performances, particularly from Firth, Egerton (sure to get a lot of work off the back of this), Jackson and Strong, and Sofia Boutella’s blade-legged henchwoman is yet another why-has-no-one-done-that great idea.

Not everything hinges on being wall-to-wall groundbreaking, though, and Kingsman has so much to recommend it. It ticks all the requisite boxes of being exciting and funny, and some of its sequences are executed breathtakingly. The plot may move along familiar tracks — deliberately so — but it pulls out a few mysteries and surprises along the way. There’s an array of likeable performances, particularly from Firth, Egerton (sure to get a lot of work off the back of this), Jackson and Strong, and Sofia Boutella’s blade-legged henchwoman is yet another why-has-no-one-done-that great idea. I like cake. It’s all soft and sweet and tasty. But I don’t like cake as much as Stephen Neale, the protagonist of Ministry of Fear.

I like cake. It’s all soft and sweet and tasty. But I don’t like cake as much as Stephen Neale, the protagonist of Ministry of Fear. Ministry of Fear isn’t really about cake, but the opening 20 minutes or so plays out more or less as above and it is rather amusing. Less amusing — and, in fact, part of the film’s biggest problem — is a ‘humorous’ epilogue that returns to the cake theme. I found it hilariously funny, but unfortunately for all the wrong reasons. The other part of the problem is the abrupt ending that immediately precedes this brief coda. On the bright side, everything is resolved and you can imagine the post-climax resolution scene for yourself, but it still leaves the tale’s telling cut short.

Ministry of Fear isn’t really about cake, but the opening 20 minutes or so plays out more or less as above and it is rather amusing. Less amusing — and, in fact, part of the film’s biggest problem — is a ‘humorous’ epilogue that returns to the cake theme. I found it hilariously funny, but unfortunately for all the wrong reasons. The other part of the problem is the abrupt ending that immediately precedes this brief coda. On the bright side, everything is resolved and you can imagine the post-climax resolution scene for yourself, but it still leaves the tale’s telling cut short. The train cake theft and chase, for instance, could be thoroughly laughable thanks to the cake element and what’s clearly a studio-built wood/wasteland, but it’s atmospherically shot and, in its main burst of genius, scored only by the drone of a Nazi air raid taking place overhead. It makes for a more tense and effective soundtrack than most musical scores manage.

The train cake theft and chase, for instance, could be thoroughly laughable thanks to the cake element and what’s clearly a studio-built wood/wasteland, but it’s atmospherically shot and, in its main burst of genius, scored only by the drone of a Nazi air raid taking place overhead. It makes for a more tense and effective soundtrack than most musical scores manage.