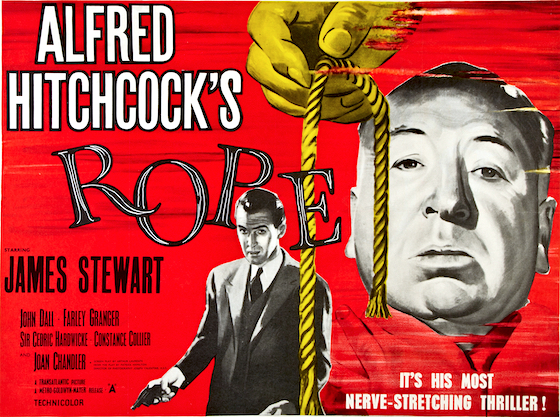

Alfred Hitchcock | 81 mins | Blu-ray | 1.33:1 | USA / English | PG / PG

Nowadays fake single takes are all over the place — some of them even last whole movies. But, as with so much cinematic trickery, it’s not actually a new idea. I don’t know if Alfred Hitchcock was the first director to attempt to trick the viewer into thinking they were watching one long take, when in fact it’s several shots stitched together via hidden cuts, but his effort is certainly one of the most famous. As an exercise in style, it’s a mixed success. Hitch is presumably inventing techniques that other filmmakers would polish and perfect in later attempts at the same stunt, but these first attempts don’t always come off perfectly. For example, every ‘hidden’ cut comes via an unmotivated camera move into the back of someone’s jacket — it may hide the cut in a literal sense, but there’s no doubting what’s going on. The entire movie is staged in actual long takes — just ten in total, most of them running seven to ten minutes. That means there are just nine cuts in the entire film, but several times (four, to be precise) Hitch just gives in and resorts to a regular cut. Sometimes you have to put the needs of the story before your showing off, I guess.

But, in other ways, the film is a great technical success. The camera moves elegantly around the apartment, employing moveable walls and stagehands shifting props while out of shot to get the moves Hitch was after. A large window at the back of the set shows a cityscape, which in other films would’ve just been a photo blowup, but here is made more convincing and alive with smoke and lights. Similarly, the passing of time is subtly emphasised because, through that window, we can see the sunlight gradually transition from daytime to evening. All of this helps sell the fact that the film takes place in real-time… sort of. Although it only runs 80 minutes, scientific analysis (yes, some scientists analyse this kind of thing) has shown the events cover about 100 minutes. Certain action is sped-up to close that gap — for example, the sun sets too quickly. Apparently this is so effective that the analysis concluded audience members feel like they’ve watched a 100-minute movie, even though it’s only 80… which, er, I don’t think was meant to sound like a criticism…

Ostensibly based on Patrick Hamilton’s play of the same name, which in turn was inspired by the Leopold and Loeb case (also the inspiration for Compulsion, amongst various other works of fiction), this adaptation changes the setting, almost all of the character names, and some of their personality traits too. Wherever they come from, the film offers an interesting array of characters. The most obvious are the two murderers — smug, cocky Brandon and worrisome Phillip — along with James Stewart, who portrays a gradual realisation that something is amis, culminating in devastation at what was really a silly thought exercise being writ into reality. Apparently Stewart thought he was miscast, but I think he’s very good, conveying much with just looks and expressions, and making you believe his moral about-turn at the end.

Other parts have, perhaps, dated: the film attracted some controversy for its homosexual overtones, but to modern eyes there’s very little to emphasise such an interpretation. Perhaps some social cues that once indicated homosexuality have fallen by the wayside in the past seven decades; or perhaps, because there’s no need to bury such things anymore, what was once ‘weird’ is now just normal behaviour. Nonetheless, much of the screenplay remains quite fun, including various nods and winks to the situation, and one slightly meta scene where two female characters talk about male movie stars they adore in front of Jimmy Stewart. But there are also sequences of familiarly Hitchcockian suspense, one great bit coming when all the characters are distracted chatting but we’re watching the maid who, while she slowly clears stuff away, is on course to discover the hidden body…

As the end credits roll, the actor who plays David — the victim, who dies in the first shot of the movie; really, no more than a prop — Is listed first, and then every other character is defined in relation to him. It’s almost like they film’s very credits are underlining the message of the film: that no one’s inferior, including David; like they’re giving him some kind of dignity in death by making him the focus of the final element of the film. It’s another neat little trick in a film that’s full of them.

Rope was viewed as part of Blindspot 2019.

A woman wakes up on a beach in the middle of the night. Stumbling away, she comes across a beach house with three strangers inside. They establish that the last thing they remember was being in a nightclub when there was some kind of accident, and then they woke up here. Fortunately, they’re not stupid and quickly twig this place is some kind of afterlife, then begin to work out how to get out — not that they’re helped by the lighthouse beam which causes immense pain, or that if they run away from the house they end up back at the house, or the vicious smoke-monster that’s flying around…

A woman wakes up on a beach in the middle of the night. Stumbling away, she comes across a beach house with three strangers inside. They establish that the last thing they remember was being in a nightclub when there was some kind of accident, and then they woke up here. Fortunately, they’re not stupid and quickly twig this place is some kind of afterlife, then begin to work out how to get out — not that they’re helped by the lighthouse beam which causes immense pain, or that if they run away from the house they end up back at the house, or the vicious smoke-monster that’s flying around… AfterDeath is billed in part as a horror, emphasised by the skull imagery used on the poster. It’s not particularly scary though, so if you’re after that kind of thrill then it’s one to miss. As single-location mysteries go, it’s not remarkably original or exceptionally engaging, but the story and its revelations are solidly executed and the whole is decently performed, providing you don’t strain your eyes trying to see what’s happening.

AfterDeath is billed in part as a horror, emphasised by the skull imagery used on the poster. It’s not particularly scary though, so if you’re after that kind of thrill then it’s one to miss. As single-location mysteries go, it’s not remarkably original or exceptionally engaging, but the story and its revelations are solidly executed and the whole is decently performed, providing you don’t strain your eyes trying to see what’s happening. This isn’t something I normally do, but certain factors made me want to review these two films together. They’re both low-budget single-location sci-fi thrillers, but they’re also both more about humanity than ideas — they use sci-fi high concepts as a way to expose, examine, and comment on human behaviour. That I happened to watch them back to back only highlighted the similarities.

This isn’t something I normally do, but certain factors made me want to review these two films together. They’re both low-budget single-location sci-fi thrillers, but they’re also both more about humanity than ideas — they use sci-fi high concepts as a way to expose, examine, and comment on human behaviour. That I happened to watch them back to back only highlighted the similarities. Circle, on the other hand, must’ve been very tightly constructed. A group of fifty people wake up stood in two circles in a black space, with an array of arrows on the floor in front of them. Every couple of minutes, a klaxon blares out a countdown and one of them is killed. They soon realise they have some control over this, so together they try to work out what’s going on and how to escape, whilst constantly having to select who’s next. Broadly speaking, this is a high-concept thriller in the vein of

Circle, on the other hand, must’ve been very tightly constructed. A group of fifty people wake up stood in two circles in a black space, with an array of arrows on the floor in front of them. Every couple of minutes, a klaxon blares out a countdown and one of them is killed. They soon realise they have some control over this, so together they try to work out what’s going on and how to escape, whilst constantly having to select who’s next. Broadly speaking, this is a high-concept thriller in the vein of  However, it’s clear Byrkit’s focus lay elsewhere. Thematically, it’s about our fear of others, but, as Byrkit explains in

However, it’s clear Byrkit’s focus lay elsewhere. Thematically, it’s about our fear of others, but, as Byrkit explains in  With fewer to illuminate they’re less quickly-sketched than Circle’s mass of ‘contestants’, and so feel more like rounded humans. By the end, they’re doing things that might initially seem out of character, but actually aren’t at all. (If you can take it, dear reader, there’s a crazy-detailed explanation of the ending (one reading of it, anyway) to be found

With fewer to illuminate they’re less quickly-sketched than Circle’s mass of ‘contestants’, and so feel more like rounded humans. By the end, they’re doing things that might initially seem out of character, but actually aren’t at all. (If you can take it, dear reader, there’s a crazy-detailed explanation of the ending (one reading of it, anyway) to be found

If you’ve ever found a late-night train commute dull, this single-location thriller may make you rethink any complaints. Half-a-dozen people travelling from London to Tunbridge Wells find their train speeding out of control. It’s up to them to discover what’s happening and how to stop it.

If you’ve ever found a late-night train commute dull, this single-location thriller may make you rethink any complaints. Half-a-dozen people travelling from London to Tunbridge Wells find their train speeding out of control. It’s up to them to discover what’s happening and how to stop it. Often noted merely for being filmed in Los Angeles’ busy train station, there are some spirited defences of Union Station to be

Often noted merely for being filmed in Los Angeles’ busy train station, there are some spirited defences of Union Station to be  There’s an argument that the less you know going into any film the better. Naturally there are some films this applies to more than others, and Exam is one such film. Eight young professional types go into a job exam/interview; the next hour-and-a-half is all mysteries and riddles — which is why you wouldn’t want to know too much.

There’s an argument that the less you know going into any film the better. Naturally there are some films this applies to more than others, and Exam is one such film. Eight young professional types go into a job exam/interview; the next hour-and-a-half is all mysteries and riddles — which is why you wouldn’t want to know too much. Such a contained story relies heavily on its characters and the actors’ performances. Largely a cast of un- (or little-) knowns, all are decent — one or two may be subpar, but I’ve seen a lot worse. I don’t quite understand how some viewers can find White, played by Luke Mably, to be a completely likeable character in spite of his obvious flaws — he has his moments, but surely he’s not agreeable overall? Not a jot. That said, his is the standout part, a scene-stealing performance from Mably. There’s no clear-cut audience-favourite, which (from reading a few reviews) seems to be a problem for some viewers. As far as I’m concerned, it’s a good thing: never mind the realism of there being one perfect person every viewer will love, audience-favourites will either predictably win or be shockingly dispatched, so what’s the point?

Such a contained story relies heavily on its characters and the actors’ performances. Largely a cast of un- (or little-) knowns, all are decent — one or two may be subpar, but I’ve seen a lot worse. I don’t quite understand how some viewers can find White, played by Luke Mably, to be a completely likeable character in spite of his obvious flaws — he has his moments, but surely he’s not agreeable overall? Not a jot. That said, his is the standout part, a scene-stealing performance from Mably. There’s no clear-cut audience-favourite, which (from reading a few reviews) seems to be a problem for some viewers. As far as I’m concerned, it’s a good thing: never mind the realism of there being one perfect person every viewer will love, audience-favourites will either predictably win or be shockingly dispatched, so what’s the point? it’s quite nice to find a plot that doesn’t feel the need to tie everything in to its reveal; a plot that can wrong-foot you by occasionally focusing on something that’s ultimately irrelevant.

it’s quite nice to find a plot that doesn’t feel the need to tie everything in to its reveal; a plot that can wrong-foot you by occasionally focusing on something that’s ultimately irrelevant. and films that invite pondering tend to invite repeat viewing; but then again it works equally well (better, ultimately) as a straight-up “what’s going on?” thriller.

and films that invite pondering tend to invite repeat viewing; but then again it works equally well (better, ultimately) as a straight-up “what’s going on?” thriller.