Paul Leni | 110 mins | Blu-ray | 1.20:1 | USA / silent | PG

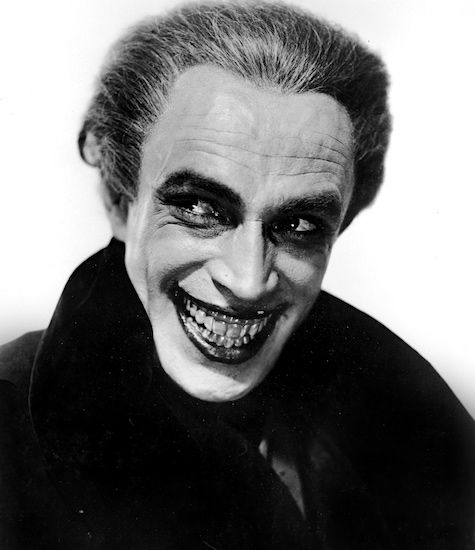

Just over 90 years ago, in the final years of the silent era, The Man Who Laughs was a “super-production” — an expensive and major release, designed to follow in the footsteps of successes like The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Phantom of the Opera, with an acclaimed imported director (Paul Leni, Waxworks) and star (Conrad Veidt, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari), a shared leading lady from Phantom (Mary Philbin), and adapted from another novel by the author of Hunchback (Victor Hugo). It did, I believe, live up to its pedigree and expectations. But today it’s primarily remembered for one thing: being the visual inspiration behind a certain comic book supervillain…

Perhaps because of the connections to the aforementioned films, and because it inspired such a violent character, and because of the publicity stills that inspired that look, and because its production studio (Universal) would shortly become renowned for their iconic interpretations of the cornerstones of horror (Dracula, Frankenstein, et al), The Man Who Laughs has often been cited as a horror movie. It isn’t. Well, some of the first 15 minutes do play a bit like one — execution by iron maiden; mutilation and abandonment of a child; dangling corpses of hanged men — but then it jumps forward in time and becomes a romantic melodrama, with a bit of antiestablishment satire and a swashbuckling climax thrown in for good measure.

The story begins in 1690, with King James II punishing a rebellious lord by handing his son, Gwynplaine, to comprachicos (invented by Hugo for the novel; it means “child-buyers”) who mutilate the boy’s mouth into a permanent grin. And then he executes the lord in an iron maiden for good measure. When all the comprachicos are later exiled, they abandon the boy. Wandering through the snow, the kid finds a woman frozen to death, but her baby still alive in her arms. (Like I said, the first 15 minutes are pretty bleak.) He rescues the baby, who it’ll turn out is blind, and soon the pair are taken in by a wandering performer, Ursus (Cesare Gravina). Jump forward a couple of decades and Gwynplaine (Veidt) is now a popular attraction himself thanks to his laughing face, and the baby has grown into a beautiful young woman, Dea (Philbin), and the pair are in love. Let’s not think too much about the background to that relationship, eh? Gwynplaine feels unworthy of Dea’s love because he’s so hideous, but she doesn’t care because she’s literally blind.

Meanwhile, Gwynplaine’s fame and unique facial features lead to it being discovered that he’s really a noble, kicking off a bunch of courtly intrigue — I could explain it, but then we’d just be getting into the plot of the entire movie. Suffice to say, it involves a scheming courtier, Barkilphedro (Brandon Hurst), who was partly responsible for Gwynplaine’s dad’s death; a horny duchess, Josiana (Olga Baclanova), who we first meet while a peasant messenger spies on her having a bath (nothing explicit is actually seen — it cuts away just in time — but it was still too risqué for British censors, who cut away even sooner); and Queen Anne (Josphine Cromwell), best known today as “the one Olivia Colman played in The Favourite (there’s considerably less swearing, gout, lesbianism, and bunny rabbits in this version).

With the “beauty and the beast” angle to the film’s central romance, the film does withstand comparison to other variations of that story — like, um, Beauty and the Beast, but also, again, The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The difference here is in how people react to the ‘beast’. Only he himself seems to find him monstrous. The public find him inescapably hilarious, which isn’t nice for him to live with, but has made him popular and beloved rather than reviled. The love of his life is besotted with him unconditionally. Josiana comes to see his show and for some reason finds him instantly attractive (in fairness, I think she’s attracted to any man with a pulse).

A more apt comparison is to a film made over 50 years later, David Lynch’s The Elephant Man — a parallel I spotted for myself, but also is mentioned in two essays in the booklet accompanying Eureka’s new Blu-ray release, so I’m certainly not alone in feeling this. Both concern a man who is physically disfigured and has fallen in with fairground sideshow folk, who despises himself but comes to find love and compassion from others. They even both climax with a grandstanding speech where the man in question declares his worth to the world, with the famous “I am a human being!” bit from The Elephant Man seeming like an echo of a scene here where Gwynplaine, forced to join the House of Lords by order of the Queen, eventually rejects her command, declaring his independence with the assertion that “God made me a man!” As Travis Crawford writes in the aforementioned booklet, “while sinister clowns would ultimately become an unlikely horror cliche, Gwynplaine’s gruesome disfigurement makes him a figure of pity, not menace… more Pierrot than Pennywise.” The Man Who Laughs is less concerned with examining and affirming the fundamental humanity underneath ‘freaks’ than Lynch’s film (this is a classical melodrama, after all), but it’s certainly an aspect of the story that, despite how he looks, Gwynplaine is still a human being; that, despite his fixed grin, he’s full of all the emotions of any human being.

Before I go, a quick word on the film’s soundtrack. “But it’s a silent movie.” Yes, but as you surely know, silent movies aren’t meant to be watched actually silent. The Blu-ray release (both the new UK one and an earlier US one from Flicker Alley) comes with two audio options: a new 2018 score by the Berklee Silent Film Orchestra, and the original 1928 Movietone sync track, which is not just general music backing but also includes some music clearly framed as diegetic, plus occasional sound effects, and even dialogue (in the form of background crowd noise, mostly). Now, the film was originally released as silent, then withdrawn and re-released with this accompanying soundtrack, so I guess the option of a new score isn’t wholly unmerited. Nonetheless, it still seems slightly off to me that you’d supplant an authentic original track with a modern creation. As if to underline this point, the booklet reveals that the new score is actually little more than a final-year project by a group of students! It’s lovely for them that they were able to present their work at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and it was well received, and that it’s now included as an option on the film’s official releases… but presenting it as the primary audio option? No thanks. I suggest you choose the 1928 soundtrack.

It’s probably unlikely that The Man Who Laughs can escape its status as a trivia footnote for the Joker at this point (heck, Flicker Alley’s release even plays up the connection on its cover, taking the film’s most Joker-esque photo and decorating it in the character’s colours of purple and green). Certainly, no one should watch it for that reason alone — the inspiration for the Joker begins and ends with the grinning-man imagery; there’s nothing in the film itself that contributes to the character. There’s also little here to support its reputation as an influential early horror movie — those seeking horror thrills shouldn’t watch for that reason either. But for all the things The Man Who Laughs is not, what it is is a well-made and performed drama; one that deserves to stand and be appreciated on its own merits, not those that others have mistakenly conferred on it.

The Man Who Laughs is released on Blu-ray in the UK today.

The word “prequel” was first coined in the ’50s, arguably entered the mainstream in the ’70s, and was firmly established as a term everyone knew and used in the ’90s by the Star Wars prequel trilogy. Works that can be defined as prequels predate their naming, however, and surely one of the earliest examples in the movies must be this silent German horror.

The word “prequel” was first coined in the ’50s, arguably entered the mainstream in the ’70s, and was firmly established as a term everyone knew and used in the ’90s by the Star Wars prequel trilogy. Works that can be defined as prequels predate their naming, however, and surely one of the earliest examples in the movies must be this silent German horror. Regarded as one of the first horror films, The Golem is more of a moderately-dark fantasy, or a fairytale-type myth. There are clear similarities to Frankenstein, though I don’t know if either influenced the other. However, it does feature what I presume is one of first instances of that most daft of horror tropes: running upstairs to escape the monster. It goes as well here as it ever does, i.e. not very. Said monster looks a bit comical by today’s standards. Built by the rabbi to defend the Jewish people, he immediately uses the hulking chap to chop wood and run errands — he doesn’t want a defender, he wants a servant! A terrifying beast nonetheless, it’s ultimately defeated because it picks up a little girl for a cuddle and she casually removes its magic life-giving amulet.

Regarded as one of the first horror films, The Golem is more of a moderately-dark fantasy, or a fairytale-type myth. There are clear similarities to Frankenstein, though I don’t know if either influenced the other. However, it does feature what I presume is one of first instances of that most daft of horror tropes: running upstairs to escape the monster. It goes as well here as it ever does, i.e. not very. Said monster looks a bit comical by today’s standards. Built by the rabbi to defend the Jewish people, he immediately uses the hulking chap to chop wood and run errands — he doesn’t want a defender, he wants a servant! A terrifying beast nonetheless, it’s ultimately defeated because it picks up a little girl for a cuddle and she casually removes its magic life-giving amulet. Shaun the Sheep started life in the 1995 Wallace & Gromit short

Shaun the Sheep started life in the 1995 Wallace & Gromit short  (that US PG is thanks to a couple of oh-so-rude fart jokes), but there’s a sophistication to the way that simplicity is handled that adults can enjoy. There are also references and in-jokes for the grown-ups; not hidden dirty jokes that’ll put you in the awkward position of having to explain to the kids why you were laughing, but neat puns (note the towns that the Big City is twinned with) and references to other films (like

(that US PG is thanks to a couple of oh-so-rude fart jokes), but there’s a sophistication to the way that simplicity is handled that adults can enjoy. There are also references and in-jokes for the grown-ups; not hidden dirty jokes that’ll put you in the awkward position of having to explain to the kids why you were laughing, but neat puns (note the towns that the Big City is twinned with) and references to other films (like  Douglas Fairbanks started out in comedies, where he was so popular he was quickly established as “the King of Hollywood”, which allowed him to attempt something different: an historical adventure film.

Douglas Fairbanks started out in comedies, where he was so popular he was quickly established as “the King of Hollywood”, which allowed him to attempt something different: an historical adventure film.  of course, which alerts the Mongol Prince to the attempted deception — though as he’s “the Governor of Wah Hoo and the Island of Wak”, he’s a fine one to talk. The thief manages to make it to see the princess anyway. She instantly falls in love with him, and he realises he loves her too, so can’t just kidnap her. His whole value system is undermined! But now he’ll have to win her hand by more honest means. Well, she already loves him, so he’s halfway there; but he’s an imposter, so there’s that to sort out yet.

of course, which alerts the Mongol Prince to the attempted deception — though as he’s “the Governor of Wah Hoo and the Island of Wak”, he’s a fine one to talk. The thief manages to make it to see the princess anyway. She instantly falls in love with him, and he realises he loves her too, so can’t just kidnap her. His whole value system is undermined! But now he’ll have to win her hand by more honest means. Well, she already loves him, so he’s halfway there; but he’s an imposter, so there’s that to sort out yet. Even more impressive are the sets. The work of famed Hollywood designer William Cameron Menzies, at the time Fairbanks felt Menzies was too inexperienced to work on such a big project. Undeterred, he created a collection of detailed drawings and convinced the star/producer. No surprise that worked, because Menzies’ designs are extraordinary. His complex, detailed, unreal drawings are recreated accurately on screen (examples of this can be seen in the ‘video essay’ included on the film’s Blu-ray releases, for instance), using numerous techniques to create truly fantastical scenes: ginormous sets (they covered six-and-a-half acres), built on a reflective enamel floor (which had to be constantly re-enamelled throughout the shoot) and painted in certain ways to make them appear floaty; or glass matte paintings used to seamlessly extended or enhance shots. Reportedly 20,000 feet of film — that’s hours and hours worth — were shot just to test the lighting and painting of the sets.

Even more impressive are the sets. The work of famed Hollywood designer William Cameron Menzies, at the time Fairbanks felt Menzies was too inexperienced to work on such a big project. Undeterred, he created a collection of detailed drawings and convinced the star/producer. No surprise that worked, because Menzies’ designs are extraordinary. His complex, detailed, unreal drawings are recreated accurately on screen (examples of this can be seen in the ‘video essay’ included on the film’s Blu-ray releases, for instance), using numerous techniques to create truly fantastical scenes: ginormous sets (they covered six-and-a-half acres), built on a reflective enamel floor (which had to be constantly re-enamelled throughout the shoot) and painted in certain ways to make them appear floaty; or glass matte paintings used to seamlessly extended or enhance shots. Reportedly 20,000 feet of film — that’s hours and hours worth — were shot just to test the lighting and painting of the sets. In a star-making supporting role, Anna May Wong is indeed memorable as a traitorous handmaiden. That’s more than can be said of her employer: Johnston is a bit of a non-starter as the princess, which I guess is what happens when you have to re-cast because your original choice departs part way through production. Comedian Snitz Edwards was also a mid-production replacement, drafted in to provide comic relief. It wasn’t necessary: he doesn’t add much, and Fairbanks had it covered.

In a star-making supporting role, Anna May Wong is indeed memorable as a traitorous handmaiden. That’s more than can be said of her employer: Johnston is a bit of a non-starter as the princess, which I guess is what happens when you have to re-cast because your original choice departs part way through production. Comedian Snitz Edwards was also a mid-production replacement, drafted in to provide comic relief. It wasn’t necessary: he doesn’t add much, and Fairbanks had it covered. Students of the Oscars well know that, technically speaking, there wasn’t a single “Best Picture” award at the inaugural Academy Awards ceremony in 1929. Instead, there were two awards that covered that ground, seen (at the time) as being of equal significance. One was for “Unique and Artistic Production” — which I’d argue is more or less what most people think Best Picture represents today. That was given to F.W. Murnau’s

Students of the Oscars well know that, technically speaking, there wasn’t a single “Best Picture” award at the inaugural Academy Awards ceremony in 1929. Instead, there were two awards that covered that ground, seen (at the time) as being of equal significance. One was for “Unique and Artistic Production” — which I’d argue is more or less what most people think Best Picture represents today. That was given to F.W. Murnau’s  he learnt to fly just for the film), and, mid-flight, had to film their own close-ups by switching on battery-operated cameras mounted in front of them. You wouldn’t know it from watching the film itself, though: even today, the action sequences carry a palpable air of excitement, aided (perhaps even created) by the knowledge that it was all done for real — including the crashes.

he learnt to fly just for the film), and, mid-flight, had to film their own close-ups by switching on battery-operated cameras mounted in front of them. You wouldn’t know it from watching the film itself, though: even today, the action sequences carry a palpable air of excitement, aided (perhaps even created) by the knowledge that it was all done for real — including the crashes. bomb-pockmarked battlefield. Those bomb craters were, in fact, genuine: the military spent a few days before filming using the location for target practice. The climactic battle that occurred on this site was filmed with up to 19 cameras at once, including some mounted on four towers, the highest of which reached 100ft. I know this is a review, not a catalogue of production numbers, but it’s quite incredible.

bomb-pockmarked battlefield. Those bomb craters were, in fact, genuine: the military spent a few days before filming using the location for target practice. The climactic battle that occurred on this site was filmed with up to 19 cameras at once, including some mounted on four towers, the highest of which reached 100ft. I know this is a review, not a catalogue of production numbers, but it’s quite incredible. How much these factors affect the film’s quality seems to be very much a personal matter. Wings set the stall for many a Best Picture winner to follow by being not that well regarded by critics; indeed, more time and praise is given to its top-award compatriot, Sunrise. For the most part, I found the personal dramas passable enough, with a few outstanding scenes — David’s farewell to his stoical parents; Cooper’s scene; the bubbles (at first). However, the combat sequences, and in particular the aerial photography, are stunning; so impressive as to easily offset whatever doubts the other elements may engender.

How much these factors affect the film’s quality seems to be very much a personal matter. Wings set the stall for many a Best Picture winner to follow by being not that well regarded by critics; indeed, more time and praise is given to its top-award compatriot, Sunrise. For the most part, I found the personal dramas passable enough, with a few outstanding scenes — David’s farewell to his stoical parents; Cooper’s scene; the bubbles (at first). However, the combat sequences, and in particular the aerial photography, are stunning; so impressive as to easily offset whatever doubts the other elements may engender. But I digress. Wings is a film that deserves to be remembered as more than a mere footnote. It’s not just a trivia answer to “what was the first Best Picture?”, but a worthy winner of that prize; a movie that, almost 90 years after it was produced, still has the power to elicit excitement and awe. Wellman’s picture may not have been deemed unique or artistic, even though it’s definitely the former and possibly the latter, but it was deemed outstanding, and it’s definitely that.

But I digress. Wings is a film that deserves to be remembered as more than a mere footnote. It’s not just a trivia answer to “what was the first Best Picture?”, but a worthy winner of that prize; a movie that, almost 90 years after it was produced, still has the power to elicit excitement and awe. Wellman’s picture may not have been deemed unique or artistic, even though it’s definitely the former and possibly the latter, but it was deemed outstanding, and it’s definitely that. Poorly reviewed and a box office flop on its release, Buster Keaton’s The General has undergone a stark re-evaluation since: the United States National Film Registry deemed it so “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” that it was added to the registry in its first year, alongside the likes of

Poorly reviewed and a box office flop on its release, Buster Keaton’s The General has undergone a stark re-evaluation since: the United States National Film Registry deemed it so “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” that it was added to the registry in its first year, alongside the likes of  It was reportedly a very expensive film, and it looks it: there are tonnes of extras, not to mention elaborate choreography… of trains! Who knew old steam trains were so agile? There’s impressive physicality on display from Keaton, but the well-timed movements of those big old locomotives are quite extraordinary, especially for the era (I mean, for the past couple of decades you’ve been able to do pretty much anything thanks to a spot of computer-controlled what-have-you. Not much of that going on in the 1920s.)

It was reportedly a very expensive film, and it looks it: there are tonnes of extras, not to mention elaborate choreography… of trains! Who knew old steam trains were so agile? There’s impressive physicality on display from Keaton, but the well-timed movements of those big old locomotives are quite extraordinary, especially for the era (I mean, for the past couple of decades you’ve been able to do pretty much anything thanks to a spot of computer-controlled what-have-you. Not much of that going on in the 1920s.) Widely regarded as one of the greatest movies of all time (look at

Widely regarded as one of the greatest movies of all time (look at  Dreyer based his telling on the written records of Joan’s trial. Although that’s grand for claims of historical accuracy, it’s hard to deny that silent cinema is ill-suited to thoroughly portraying something dialogue-heavy. There are many things silent film can — and, in this case, does — do very well indeed, but representing extensive verbal debate isn’t one of them. Bits where the judges argue amongst themselves — in silence, as far as the viewer is concerned — leave you longing to know what it is they’re so het up about. Sometimes it becomes clear from how events transpire; other times, not so much.

Dreyer based his telling on the written records of Joan’s trial. Although that’s grand for claims of historical accuracy, it’s hard to deny that silent cinema is ill-suited to thoroughly portraying something dialogue-heavy. There are many things silent film can — and, in this case, does — do very well indeed, but representing extensive verbal debate isn’t one of them. Bits where the judges argue amongst themselves — in silence, as far as the viewer is concerned — leave you longing to know what it is they’re so het up about. Sometimes it becomes clear from how events transpire; other times, not so much. neutral costumes on sparsely-decorated sets, and are almost entirely shot in close-ups — all elements that avoid the usual grandiosity of historical movies, both in the silent era and since. What we perceive as being ‘grand’ changes over time (things that were once “epic” can become small scale in the face of increasing budgets, for instance); pure simplicity, however, does not age much.

neutral costumes on sparsely-decorated sets, and are almost entirely shot in close-ups — all elements that avoid the usual grandiosity of historical movies, both in the silent era and since. What we perceive as being ‘grand’ changes over time (things that were once “epic” can become small scale in the face of increasing budgets, for instance); pure simplicity, however, does not age much. The actors playing the judges may be less individually memorable than Joan, but it’s their conflict — the personal battle between Joan and these men, as Dreyer saw it — that drives the film. Dreyer believed the judges felt genuine sympathy for Joan; that they did what they did not because of politics (they represented England, and she had led several successful campaigns against the Brits) but because of their devout belief in religious dogma. Dreyer says he tried to show this in the film, though it strikes me the judges still aren’t portrayed too kindly: they regularly seem contemptuous of Joan, and are outright duplicitous at times. Maybe that’s just religion for you.

The actors playing the judges may be less individually memorable than Joan, but it’s their conflict — the personal battle between Joan and these men, as Dreyer saw it — that drives the film. Dreyer believed the judges felt genuine sympathy for Joan; that they did what they did not because of politics (they represented England, and she had led several successful campaigns against the Brits) but because of their devout belief in religious dogma. Dreyer says he tried to show this in the film, though it strikes me the judges still aren’t portrayed too kindly: they regularly seem contemptuous of Joan, and are outright duplicitous at times. Maybe that’s just religion for you. however, so I have no opinion. Instead, they offer two alternatives. On the correct-speed 20fps version, there’s a piano score by silent film composer Mie Yanashita. Apparently this is the only existing score set to 20fps, and Masters of Cinema spent so much restoring the picture that there was no money left to commission an original score. Personally, I don’t think they needed to. Yanashita’s is classically styled, which works best for the style of the film, and it heightens the mood of some sequences without being overly intrusive, by and large. Compared to Dreyer’s preferred viewing method, of course it affects the viewing experience — how could it not, when it marks out scenes (with pauses or a change of tone) and emphasises the feel of sequences (with changes in tempo, for instance). That’s what film music is for, really, so obviously that’s what it does. Would the film be purer in silence? Maybe. Better? That’s a matter of taste. This particular score is very good, though.

however, so I have no opinion. Instead, they offer two alternatives. On the correct-speed 20fps version, there’s a piano score by silent film composer Mie Yanashita. Apparently this is the only existing score set to 20fps, and Masters of Cinema spent so much restoring the picture that there was no money left to commission an original score. Personally, I don’t think they needed to. Yanashita’s is classically styled, which works best for the style of the film, and it heightens the mood of some sequences without being overly intrusive, by and large. Compared to Dreyer’s preferred viewing method, of course it affects the viewing experience — how could it not, when it marks out scenes (with pauses or a change of tone) and emphasises the feel of sequences (with changes in tempo, for instance). That’s what film music is for, really, so obviously that’s what it does. Would the film be purer in silence? Maybe. Better? That’s a matter of taste. This particular score is very good, though. Some viewers describe how they’ve found The Passion of Joan of Arc to be moving, affecting, or life-changing on a par with a religious experience. I wouldn’t go that far, but then I’m not religious so perhaps not so easily swayed. As a dramatic, emotional, film-viewing experience, however, it is highly effective. As Dreyer wrote in 1950, “my film on Joan of Arc has incorrectly been called an avant-garde film, and it absolutely is not. It is not a film just for theoreticians of film, but a film of general interest for everyone and with a message for every open-minded human being.” A feat of visual storytelling unique to cinema, it struck me as an incredible movie, surprisingly accessible, and, nearly 90 years after it was made, timeless.

Some viewers describe how they’ve found The Passion of Joan of Arc to be moving, affecting, or life-changing on a par with a religious experience. I wouldn’t go that far, but then I’m not religious so perhaps not so easily swayed. As a dramatic, emotional, film-viewing experience, however, it is highly effective. As Dreyer wrote in 1950, “my film on Joan of Arc has incorrectly been called an avant-garde film, and it absolutely is not. It is not a film just for theoreticians of film, but a film of general interest for everyone and with a message for every open-minded human being.” A feat of visual storytelling unique to cinema, it struck me as an incredible movie, surprisingly accessible, and, nearly 90 years after it was made, timeless.