Part of the impetus behind this new era of 100 Films was to solve ‘problems’ like my repeated failure to post reviews. Hopefully my plan for regular groups of capsule-sized reviews will solve that going forward. But this has been an issue for a while, and that’s led to a huge backlog of unreviewed films from 2019 to 2021 — it totals a ridiculous 449 feature films (counting shorts too, it goes over 500). Rather than abandon those to the mists of time, I present a new weekly (more or less — let’s not overcommit myself) series: Archive 5.

Essentially, it’s the same format as new viewing: each post is a collection of short reviews; but here they’re five titles plucked at random from my archive of unreviewed films (and I’ve used a random number generator, so it’s genuinely unmethodical). If I can keep this up weekly, it will take me just under two years to clear the backlog — which means I could still be reviewing stuff from 2019 in 2023. Hahaha… haha… ha… ugh.

With that in mind, there’s no need for further ado. This week’s Archive 5 are…

(I Care a Lot was originally intended to be part of this post, but then the review turned out a little long, so I spun it off by itself. That’s the kind of thing I’ll probably keep doing, too.)

Never Too Young to Die

(1986)

Gil Bettman | 97 mins | digital (HD) | 1.85:1 | USA / English | 18 / R

If you dropped A View to a Kill, Rocky Horror, WarGames, and Mad Max 2 into a blender, the end result might be Never Too Young to Die. And if that sounds like a ludicrous, unpalatable mash-up… yep, that’s Never Too Young to Die.

This direct-to-video action-adventure stars a pre-Full House John Stamos as Lance Stargrove, a teenage gymnast whose dad is a secret agent (played by George Lazenby — aged 47 at the time, but looking at least 20 years older). When daddy is killed, Lance teams up with his partner (singer turned actress Vanity) to go after the culprit: gang leader and wannabe terrorist Velvet Von Ragnar (Gene Simmons (yes, from Kiss), chewing scenery as if he’s not been fed for months).

If you’ve never heard of this film… well, neither had I, until a Cracked article suggesting comical substitutes for Covid-delayed blockbusters. But what really convinced me to watch it is that it has The Greatest Trailer Ever Made. If you set out to make a spoof ’80s trailer, I’m not convinced you’d be able to beat that. Unfortunately, neither can the film as a whole. It’s fun at times (the boob-biting final fight, or a scene where Stamos tries to distract himself from Vanity’s sexuality by… eating multiple apples), but it’s not quite camp or daft enough to really earn a place as a cult classic.

I’ll say this for it, though: rewatching that trailer has made me really want to watch the film again…

Never Too Young to Die was #70 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2020.

Bachelor Knight

(1947)

aka The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer

Irving Reis | 91 mins | digital (SD) | 4:3 | USA / English | U

If you ever need to name an obscure Oscar winner for some reason, you could do worse than Bachelor Knight — or, to give it its even-dumber-sounding original title, The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer. Yes, this won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay (the other nominees aren’t the greatest field you’ve ever seen, but altogether they’re either better-remembered or were considered good enough to nominate for other gongs that evening, so quite how this took the prize, I don’t know).

The plot also stretches credibility: after high schooler Susan (Shirley Temple) becomes infatuated with artist Richard Nugent (Cary Grant), she sneaks into his place to model for him, much to the disapproval of her older sister Margaret (Myrna Loy), who also happens to be a judge; and when Nugent ends up in her court room, she sentences him to date Susan until her infatuation inevitably wears itself out. I know things are different in the US, and also in the past, but did/do judges there really have the power to hand out any crazy made-up sentences they like?

On the bright side, the film moves sprightly through its plot. Perhaps that’s because it takes a whole 40 minutes to get through the basic setup, even while running at a pace, means there’s less screen time left to dwell on all that follows. Not that some individual bits don’t go on a tad, like a picnic sequence; but others work very well, like a scene in a nightclub that is a nicely-written bit of escalating farce.

It’s not the best work of anyone involved, but Bachelor Knight belies its iffy title (both of them) to be a likeable-enough 90 minutes of screwball comedy.

Bachelor Knight was #70 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2021.

Little Women

(2019)

Greta Gerwig | 135 mins | cinema | 1.85:1 | USA / English | U / PG

Writer-director Greta Gerwig’s adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s beloved novel was greeted in some quarters by questions of if it was necessary: it’s the sixth big-screen version of Alcott’s book, and came just two years after a major new BBC adaptation. Well, I don’t know if it was ‘necessary’ or not, but Gerwig’s version is definitely a very good film.

A key point that marks it out from other adaptations is that Gerwig has restructured the story: instead of playing out in a straightforward chronological fashion, it flashes back and forth in the sisters’ lives, starting with them as young women in 1868, with Jo in New York and Amy in Paris, before mixing in events from their childhood, seven years earlier, when the four sisters lived together in Massachusetts. This might seem like a rejig for the sake of differentiation, but Gerwig uses it to create interesting juxtapositions or to reframe plot points. For one example (spoilers follow, if you’re not familiar with the story), I felt it made Laurie and Amy’s relationship less creepy. Told chronologically, they first meet when he’s a young man and she’s a child, and he only moves his affection to her after Jo’s rejected him and Amy’s grown up. In Gerwig’s version, we first meet them together in Paris, and they seem more destined for each other, with a genuine spark between them as individuals, rather than a nagging sense of “if I can’t have one sister, this other will do”. It’s only later we learn the full backstory of Laurie and Jo — and, for that matter, of Jo and Amy — which, yeah, is obviously still a bit creepy, when you think about it.

Whichever way you cut it, Gerwig seems to really get to the heart of the meaning in the story and characters, as well as giving it a lightly feminist polish (misogynists would probably consider it Terribly Feminist and Evilly Revisionist, if they watched it, which I don’t imagine they would). A star-studded cast ensure the whole thing is well acted, and it’s beautifully shot by cinematographer Yorick Le Saux. Questions about ‘necessariness’ are particularly irrelevant when the work is this good.

Little Women was #4 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2020.

Aniara

(2018)

Pella Kågerman & Hugo Lilja | 106 mins | digital (HD) | 2.35:1 | Sweden & Denmark / Swedish & English | 18 / R

A sci-fi movie based on, somewhat oddly, a 1950s Swedish poem, Aniara is about a spaceship transporting migrators from Earth to Mars that accidentally veers off course and heads irretrievably into deep space. Rather than the kind of action-adventure this might provoke if it were a Hollywood production, Aniara follows how the passengers and crew attempt to cope with their new lives.

It’s a premise interesting enough that you feel it could fuel a TV series — how this mass of people, forced together by accident and terrible circumstance, comes to function (or not) as a society. Or maybe the remake of Battlestar Galactica already nailed that kinda thing. Either way, here it’s condensed into about 100 minutes; and because it has such a long-term view of what it wants to pack in, there are some surprisingly large time jumps (by the half-hour mark we’ve already reached Year 3). It takes some odd detours when it does that (society completely breaks down into weirdo cults… then a probe that might allow them to return home is discovered, at which point everything goes back to normal), but overall it has a pretty clear thesis about humanity and how we cope with things — “not well”, fundamentally.

The final act kind of rushes a similar point, skipping ahead (several times) to how things are even worse without really tracking the descent. Maybe that’s why I liked the idea of a series version so much: to fill in all those blanks. But I don’t want to take this criticism too much to heart. If anything, the fact I wanted more detail is a compliment. It’s not the film bungling developments and me searching for justification, but rather that I’d be interested in seeing the themes and characters explored in even more detail. As it stands, Aniara is an epic-scale story told well in a somewhat condensed fashion.

Aniara was #65 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2020. It placed 21st on my list of The Best Films I Saw in 2020.

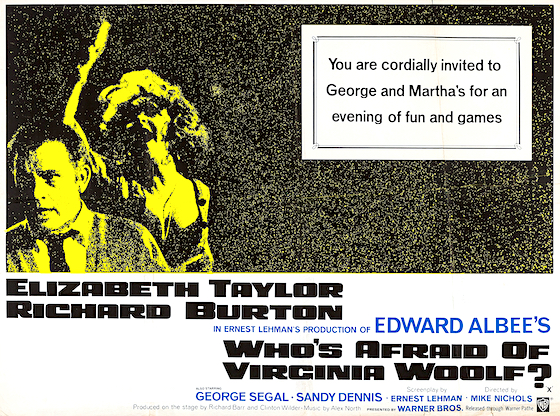

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

(1966)

Mike Nichols | 131 mins | Blu-ray | 1.85:1 | USA / English | 12

When a middle-aged college professor (Richard Burton) and his wife (Elizabeth Taylor) have his new young colleague (George Segal) and wife (Sandy Dennis) around for drinks one evening, the occasion soon degenerates into a verbal slanging match between the elder couple, the younger inescapably caught in the middle.

And as the film takes place in almost-real-time, in just a couple of locations, it feels like we’re trapped with them. With a running time north of two hours, the film’s drunken sardonicism almost becomes an endurance test, particularly when it goes on a bit too long in the middle. But it’s carried through by some magnificent performances. Everyone talks about Taylor — just 33 at the time, she wasn’t sure she could play the part of a bitter 52-year-old, but she’s excellent — or they talk about Taylor and Burton — similarly, he wasn’t sure he could play a beaten-down failure of a man, having been used to taking dashing heroic roles — but Sandy Dennis is great too, and deserved her Oscar. Of the four actors, its George Segal who draws the short straw, not really getting the material to truly stand toe-to-toe with the other three (he still got an Oscar nom, though).

Director Mike Nichols insisted the film be shot in black & white, which helps it to pull off Taylor’s ageing makeup, but was also intended to stop it seeming too ‘literal’ and instead give an abstract quality. That fits the material, because the characters, events, and revelations are all pretty odd; the way it plays out pretty strange. Plus, the pitch-black darkness of the night fits the film’s themes. Cinematographer Haskell Wexler does a superb (indeed, Oscar-winning) job, the photography looking more striking than you might expect, or even need, for such an actor-focused character piece.

A whole featurette on the film’s disc release discusses how it was “too shocking for its time”, mainly because of the language used (the fact the film was made relatively unedited set a ball rolling that, just a couple of years later, saw the Production Code replaced by the modern MPAA classification system). While such concerns are no longer really relevant (once-controversial terms like “screw” and “goddamn” are hardly “fuck”, are they?), that the film is still powerful shows it was never truly about what was said, but who said it and how they said it. I don’t mean to say that it would still be offensive today, but rather that it still packs an emotive punch.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? was #22 in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2021.

The directorial debut of uber-hearththrob movie star Ryan Gosling is not what you might expect someone of that particular adulation to produce. It’s not just that it has a dark heart, but that it’s slow, opaque, perverted, and not easily summarisable.

The directorial debut of uber-hearththrob movie star Ryan Gosling is not what you might expect someone of that particular adulation to produce. It’s not just that it has a dark heart, but that it’s slow, opaque, perverted, and not easily summarisable. It comes to a very cathartic ending, on multiple levels. I almost didn’t realise I needed that catharsis at the end — I knew I wanted certain characters to get their comeuppance, but the load that seems to lift at the end, with all the different climaxes combined, including parts that might not seem ‘good’… well, it’s almost like Rat is right about Bones’ actions lifting a bad spell.

It comes to a very cathartic ending, on multiple levels. I almost didn’t realise I needed that catharsis at the end — I knew I wanted certain characters to get their comeuppance, but the load that seems to lift at the end, with all the different climaxes combined, including parts that might not seem ‘good’… well, it’s almost like Rat is right about Bones’ actions lifting a bad spell.

British Academy Film Awards 2016

British Academy Film Awards 2016 Adapted from Colm Tóibín’s award-winning 2009 novel by novelist-turned-screenwriter Nick Hornby and director John Crowley (

Adapted from Colm Tóibín’s award-winning 2009 novel by novelist-turned-screenwriter Nick Hornby and director John Crowley ( Guiding us through this, the film’s heart in every respect, is Saoirse Ronan’s leading performance. I will watch Ronan in essentially anything at this point, both because she seems to choose good material and because, even when she doesn’t, she’s great in it. This is probably her first really mature performance, convincing as a somewhat shy young woman who makes her way out into the world, in the process realising all the confidence she should have in herself. It’s the kind of character and performance that works by accumulation; it’s about the journey, not heavy-handed emoting in a scene or two.

Guiding us through this, the film’s heart in every respect, is Saoirse Ronan’s leading performance. I will watch Ronan in essentially anything at this point, both because she seems to choose good material and because, even when she doesn’t, she’s great in it. This is probably her first really mature performance, convincing as a somewhat shy young woman who makes her way out into the world, in the process realising all the confidence she should have in herself. It’s the kind of character and performance that works by accumulation; it’s about the journey, not heavy-handed emoting in a scene or two. John Crowley’s direction is largely unobtrusive, but that is a very different kettle of fish to lacking quality. The subtle changes in framing, lighting, and colour palette as the film moves through its locations and stages helps emphasise how Eilis is changing, and how the world changes in her perceptions, too. It makes the story’s times and places look beautiful without quite slipping into picture-postcard rose-tinted-memories territory.

John Crowley’s direction is largely unobtrusive, but that is a very different kettle of fish to lacking quality. The subtle changes in framing, lighting, and colour palette as the film moves through its locations and stages helps emphasise how Eilis is changing, and how the world changes in her perceptions, too. It makes the story’s times and places look beautiful without quite slipping into picture-postcard rose-tinted-memories territory. The latest from cult auteur Wes Anderson, which managed that rare feat of enduring from a March release to being an awards season contender, sees the peerless concierge of a magnificent mid-European hotel (Ralph Fiennes) accused of murdering a rich elderly guest (Tilda Swinton, caked in Oscar-winning prosthetics) and attempting to flee across the country to clear his name. More or less, anyway, because this is a Wes Anderson film and so it takes in all kinds of amusing asides, tangents, and recognisable cameos.

The latest from cult auteur Wes Anderson, which managed that rare feat of enduring from a March release to being an awards season contender, sees the peerless concierge of a magnificent mid-European hotel (Ralph Fiennes) accused of murdering a rich elderly guest (Tilda Swinton, caked in Oscar-winning prosthetics) and attempting to flee across the country to clear his name. More or less, anyway, because this is a Wes Anderson film and so it takes in all kinds of amusing asides, tangents, and recognisable cameos. I suppose the kooky idiosyncrasies of Anderson’s brand of storytelling and filmmaking will rub some viewers up the wrong way, looking on it all as vacuous affectations signifying nothing. To each their own, but, whatever the merits (or not) of Anderson’s style as a kind of one-man genre played out across his oeuvre, The Grand Budapest Hotel displays a synthesis of contributing elements that creates a movie that’s ceaselessly inventive, surprising, amusing, and entirely entertaining.

I suppose the kooky idiosyncrasies of Anderson’s brand of storytelling and filmmaking will rub some viewers up the wrong way, looking on it all as vacuous affectations signifying nothing. To each their own, but, whatever the merits (or not) of Anderson’s style as a kind of one-man genre played out across his oeuvre, The Grand Budapest Hotel displays a synthesis of contributing elements that creates a movie that’s ceaselessly inventive, surprising, amusing, and entirely entertaining.

After winning the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for

After winning the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for  Here, Fletcher either needs to settle on one or the other, or clearly signal his intentions earlier.

Here, Fletcher either needs to settle on one or the other, or clearly signal his intentions earlier.

18 years after he adapted Anne Rice’s seminal vampire novel Interview with the Vampire into a seminal vampire

18 years after he adapted Anne Rice’s seminal vampire novel Interview with the Vampire into a seminal vampire  The most effective part of the movie isn’t so much its plot or its mythology, though, but its atmosphere. Vampire movies take place in castles or drawing rooms, or high schools in more modern iterations. They are grand and sensuous. Any glamour in Byzantium is discarded and decrepit, like the titular hotel that Clara reshapes as a whorehouse; faded and left to ruin. The seafront is characterised by graffitied concrete, the glaring lights of arcade machines, heroin-chic Eastern European prozzies. The pier appears to have burnt down at some unspecified previous time and just been left. The only people left behind are the ones without a means of escape, stuck with their miserable lot. Clara and Eleanor fit in almost seamlessly.

The most effective part of the movie isn’t so much its plot or its mythology, though, but its atmosphere. Vampire movies take place in castles or drawing rooms, or high schools in more modern iterations. They are grand and sensuous. Any glamour in Byzantium is discarded and decrepit, like the titular hotel that Clara reshapes as a whorehouse; faded and left to ruin. The seafront is characterised by graffitied concrete, the glaring lights of arcade machines, heroin-chic Eastern European prozzies. The pier appears to have burnt down at some unspecified previous time and just been left. The only people left behind are the ones without a means of escape, stuck with their miserable lot. Clara and Eleanor fit in almost seamlessly. Other alleged faults include the film not giving enough time or heft to facets individual viewers want it to cover. For one example, someone criticised it for not fully exploring the issue of voluntary euthanasia. I’d argue it doesn’t explore it at all, because it’s not trying to. That Eleanor chooses to only kill people she perceives as wanting to die is not her making a moral statement on a contentious issue, but finding a way to marry her conscience and upbringing with the necessities of her vampiric life; and it’s probably practical, too. That’s not to say a vampire movie can’t be used to explore a topic like voluntary euthanasia, but if you want that I’m afraid you might have to write your own.

Other alleged faults include the film not giving enough time or heft to facets individual viewers want it to cover. For one example, someone criticised it for not fully exploring the issue of voluntary euthanasia. I’d argue it doesn’t explore it at all, because it’s not trying to. That Eleanor chooses to only kill people she perceives as wanting to die is not her making a moral statement on a contentious issue, but finding a way to marry her conscience and upbringing with the necessities of her vampiric life; and it’s probably practical, too. That’s not to say a vampire movie can’t be used to explore a topic like voluntary euthanasia, but if you want that I’m afraid you might have to write your own. Technically, DoP Sean Bobbitt grants us some gorgeous cinematography. There’s a cruel, aptly soulless beauty to the faded town, while some countryside vistas, both past and present, offer more traditional scenic pleasure. A remote rocky, misty isle — central to the mythology and so repeatedly visited — is particularly notable. Captured entirely on digital cameras, it seems sometimes that Bobbitt tried to push his equipment too hard: some shots during the climax look flat-out weird, as if someone has applied a Photoshop “comic book” filter or something. Also of note is the score by Javier Navarrete, which makes particularly good repeated use of The Coventry Carol.

Technically, DoP Sean Bobbitt grants us some gorgeous cinematography. There’s a cruel, aptly soulless beauty to the faded town, while some countryside vistas, both past and present, offer more traditional scenic pleasure. A remote rocky, misty isle — central to the mythology and so repeatedly visited — is particularly notable. Captured entirely on digital cameras, it seems sometimes that Bobbitt tried to push his equipment too hard: some shots during the climax look flat-out weird, as if someone has applied a Photoshop “comic book” filter or something. Also of note is the score by Javier Navarrete, which makes particularly good repeated use of The Coventry Carol. For all its dual-period storytelling and its grubby settings, it’s a resolutely modern kind of take on vampire mythology.

For all its dual-period storytelling and its grubby settings, it’s a resolutely modern kind of take on vampire mythology.