Bow-chicka-wow-wow!

Oh, er, no, sorry — it’s not that kind of XXX. It’s Roman numerals: this is the 30th 100-Week Roundup. (But if it is the other kind of XXX that you’re looking for, check out Roundup XX.)

Still here? Lovely. So, for the uninitiated, the 100-Week Roundup covers films I still haven’t reviewed 100 weeks after watching them. Sometimes these are short ‘proper’ reviews; sometimes they’re only quick thoughts, or even just the notes I made while viewing.

That said, as with Roundup XXIX, this week has run into some reviews that I feel would be better suited placed elsewhere; mainly, franchise entries that it would be neater to pair with their sequels. Consequently, sitting out this first roundup of May 2019 viewing are The Secret Life of Pets, Jaws 2, Ice Age: The Meltdown, and Zombieland. I’m going to have to get a wriggle on with these series roundups, though, otherwise that subsection of my backlog will get out of control…

So, actually being reviewed here are…

(1999)

Stanley Kubrick | 159 mins | Blu-ray | 16:9 | UK & USA / English | 18 / R

I seem to remember Eyes Wide Shut being received poorly on its release back in 1999, but then I would’ve only been 13 at the time so perhaps I missed something. Either way, it seems to have been accepted as a great movie in the two decades since (as is the case with almost every Kubrick movie — read something into that if you like).

Numerous lengthy, analytical pieces have been written about its brilliance. This will not be one of them — my notes only include basic, ‘witty’ observations like: one minute you’re watching a “men are from Mars, woman are from Venus” kinda relationship drama, the next Tom Cruise has taken a $74.50 cab ride from Greenwich Village to an estate in the English countryside and you’re in a Hammer horror by way of David Lynch. “A Hammer horror by way of David Lynch” is a nice description, though. That sounds like my kind of film.

And Eyes Wide Shut almost is. It’s certainly a striking, intriguing, even intoxicating film, but I didn’t find the resolution to the mystery that satisfying — I wanted something more. Perhaps I should have invested more time reading those lengthy analyses — maybe then I would be giving it a full five stars. Definitely one to revisit.

Eyes Wide Shut was viewed as part of What Do You Mean You Haven’t Seen…? 2019.

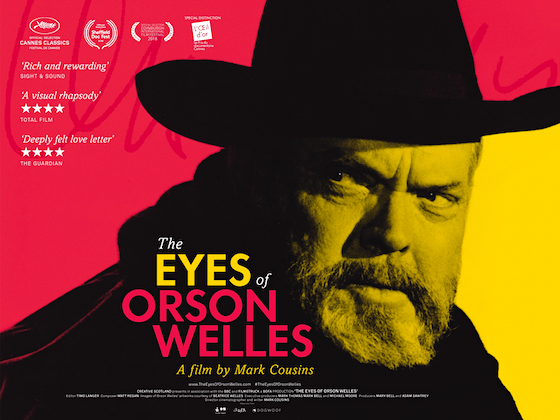

(2018)

Mark Cousins | 100 mins | TV (HD) | 16:9 | UK / English | 12

Mark Cousins, the film writer and documentarian behind the magnificent Story of Film: An Odyssey, here turns his attention to the career of one revered filmmaker: Orson Welles (obv.)

Narrated by Cousins himself, the voiceover takes the form of a letter written to Welles, which then proceeds to tell him (so it can tell us, of course) about where he went and when; about what he saw and how he interpreted it. A lot of the time it feels like it’s patronising Welles with rhetorical questions; as if Cousins is speaking to a dementia suffer who needs help to recall their own life — “Do you remember this, Orson? This is what you thought of it, isn’t it, Orson?” It makes the film quite an uneasy experience, to me; a mix of awkward and laughable.

Cousins also regularly makes pronouncements like, “you know where this is going, I’m sure,” which makes it seem like he’s constantly second-guessing himself. Perhaps it’s intended as an acknowledgement of his subject’s — his idol’s — cleverness. But it’s also presumptive: that this analysis is so obvious — so correct — that of course Welles would know where it’s going. His imagined response might be, “of course I knew where you were going, because you clearly have figured me out; you know me at least as well as I know myself.” It leaves little or no room for Welles to respond, “I disagree with that reading,” or, “I have no idea what you’re on about.” Of course, Welles can’t actually respond… but that doesn’t stop the film: near the end, Cousins has the gall to end to imagine a response from Welles, literally putting his own ideas into the man’s mouth in an act of presumptive self-validation.

I can’t deny that I learnt stuff about Orson Welles and his life from this film, but then I’ve never seen or read another comprehensive biography of the man, so that was somewhat inevitable. It’s why I give this film a passing grade, even though I found almost all of quite uncomfortable to watch.

(2016)

Richard Linklater | 112 mins | TV (HD) | 1.85:1 | USA / English | 15 / R

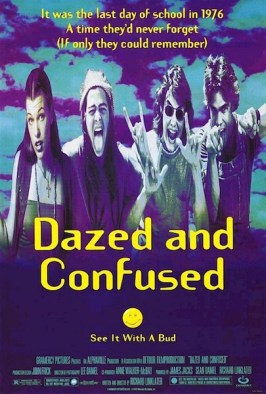

Everybody Wants Some Exclamation Mark Exclamation Mark (that’s how we should pronounce it, right?) is writer-director Richard Linklater’s “spiritual sequel” to his 1993 breakthrough movie, Dazed and Confused. That film has many fans (it’s even in the Criterion Collection), but I didn’t particularly care for it — I once referred to it as High Schoolers Are Dicks: The Movie. So while a lot of people were enthused for this followup’s existence, the comparison led me to put off watching it. A literal sequel might’ve shown some development with the characters ageing, but a “spiritual sequel”? That just sounds like code for “more of the same”.

And yes, in a way, this is High Schoolers Are Dicks 2: College Guys Are Also Dicks. It’s funny to me when people say movies like this are nostalgic and whatnot, because usually they just make me glad not to have to bother with all that college-age shit anymore. That said, in some respects the worst parts of the film are actually when it tries to get smart — when the characters start trying to psychoanalyse the behaviour of the group. Do I really believe college-age jocks ruminate on their own need for competitiveness, or the underlying motivations for their constant teasing and joking? No, I do not.

Still, while most of the characters are no less unlikeable than those in Dazed and Confused, I found the film itself marginally more enjoyable. These aren’t people I’d actually want to hang out with, and that’s a problem when the movie is just about hanging out with them; but, in spite of that, they are occasionally amusing, and we do occasionally get to laugh at (rather than with) them, so it’s not a total washout.

I seem to vaguely remember dismissing Bernie as just ‘Another Jack Black Comedy’ back whenever it came out (in the UK, that wasn’t until April 2013), and essentially forgot about it until earlier this month when it came up on

I seem to vaguely remember dismissing Bernie as just ‘Another Jack Black Comedy’ back whenever it came out (in the UK, that wasn’t until April 2013), and essentially forgot about it until earlier this month when it came up on  (If you’re observing similarities to Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil there, you’re not the first: the magazine article that inspired Bernie, published around the same time as

(If you’re observing similarities to Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil there, you’re not the first: the magazine article that inspired Bernie, published around the same time as  The local attorney seeking Bernie’s prosecution is played by man-of-the-moment Matthew McConaughey. I don’t know when we’re meant to deem the start of his “McConaissance”, but I’m not sure this really qualifies as part of it. Not that he’s bad, but it feels like the kind of played-straight comedy Southerner I’ve seen him do a few times now; indeed, it’s how he comes across in real life, from what I’ve seen. It fits the role like a glove, but doesn’t make for a remarkable performance.

The local attorney seeking Bernie’s prosecution is played by man-of-the-moment Matthew McConaughey. I don’t know when we’re meant to deem the start of his “McConaissance”, but I’m not sure this really qualifies as part of it. Not that he’s bad, but it feels like the kind of played-straight comedy Southerner I’ve seen him do a few times now; indeed, it’s how he comes across in real life, from what I’ve seen. It fits the role like a glove, but doesn’t make for a remarkable performance. 2015 Academy Awards

2015 Academy Awards Originally titled 12 Years, until

Originally titled 12 Years, until  No one gets in a shocking accident or develops a fatal illness or dies suddenly; no one is seriously bullied or mugged; no one is arrested or imprisoned; no one is made homeless; no one gets pregnant… the list could go on. Every time you second guess that — every time you think, “oh now we’re going to have something big” — the film just rolls on with normality. Just like real life does, in fact.

No one gets in a shocking accident or develops a fatal illness or dies suddenly; no one is seriously bullied or mugged; no one is arrested or imprisoned; no one is made homeless; no one gets pregnant… the list could go on. Every time you second guess that — every time you think, “oh now we’re going to have something big” — the film just rolls on with normality. Just like real life does, in fact. Even while Linklater aims for a kind of universality, this is not just about any childhood, but about childhood in the noughties — or as the Americans like to (uglily) call them, “the aughts”. Some have called it “a period film shot now” and there’s a definite truth to that. The noughties-ness isn’t made explicit, but it’s an ever-present factor. The passing of time and issues of the era are conveyed almost exclusively through background details: politics (the Iraq war, the Obama campaign), culture (Harry Potter surfaces multiple times, the best films of summer 2008 are listed), technology (GameBoys, Xboxes, Wiis; CRTs, flatscreens; the ever-evolving iMacs and iPhones), the fashion (haircuts and clothing, particularly when Mason goes all Alternative in his high school years), the music (though the vast majority of it seems pretty obscure, so good luck with finding a grounding through that). It’s those details that ground the film so much in the ’00s and early ’10s, as well as present-day societal factors, like the string of broken marriages, the lack of financial security, the good-natured suspicion and humour with which our sympathetic leads view the Bible-lovers that Mason Sr ends up married in to (can you imagine an American movie about good ol’ family values from a previous era having its leads all but declare themselves atheists?)

Even while Linklater aims for a kind of universality, this is not just about any childhood, but about childhood in the noughties — or as the Americans like to (uglily) call them, “the aughts”. Some have called it “a period film shot now” and there’s a definite truth to that. The noughties-ness isn’t made explicit, but it’s an ever-present factor. The passing of time and issues of the era are conveyed almost exclusively through background details: politics (the Iraq war, the Obama campaign), culture (Harry Potter surfaces multiple times, the best films of summer 2008 are listed), technology (GameBoys, Xboxes, Wiis; CRTs, flatscreens; the ever-evolving iMacs and iPhones), the fashion (haircuts and clothing, particularly when Mason goes all Alternative in his high school years), the music (though the vast majority of it seems pretty obscure, so good luck with finding a grounding through that). It’s those details that ground the film so much in the ’00s and early ’10s, as well as present-day societal factors, like the string of broken marriages, the lack of financial security, the good-natured suspicion and humour with which our sympathetic leads view the Bible-lovers that Mason Sr ends up married in to (can you imagine an American movie about good ol’ family values from a previous era having its leads all but declare themselves atheists?) However, it was reportedly shot entirely on 35mm, so something else must explain the changing picture quality. Perhaps that there were two cinematographers, presumably working at different times. However, as I say, during regular viewing the picture shifts are remarkably subtle, there to be spotted by cinephiles and PQ nitpickers, while going unnoticed by the general audience.

However, it was reportedly shot entirely on 35mm, so something else must explain the changing picture quality. Perhaps that there were two cinematographers, presumably working at different times. However, as I say, during regular viewing the picture shifts are remarkably subtle, there to be spotted by cinephiles and PQ nitpickers, while going unnoticed by the general audience. Some will find him irritating as he progresses through his high school years, again in the way the real-life variety of said teenagers are; others will just find it truthful. All of the acting feels incredibly ‘real’, to the point one just assumes it was all improvised. Apparently that’s not the case — according to Hawke, it was all scripted, with the exception of an amusing-with-hindsight scene in which Masons Sr and Jr discuss the potential for a

Some will find him irritating as he progresses through his high school years, again in the way the real-life variety of said teenagers are; others will just find it truthful. All of the acting feels incredibly ‘real’, to the point one just assumes it was all improvised. Apparently that’s not the case — according to Hawke, it was all scripted, with the exception of an amusing-with-hindsight scene in which Masons Sr and Jr discuss the potential for a  If you like your fiction to be about something exceptional or extraordinary, Boyhood is decidedly the opposite. Linklater has put something of the universality of childhood on screen, however. In no way can the life of Mason Jr be interpreted as a median of everyone’s experiences, but that so much within that is so relatable shows that, however different things may appear, there’s an awful lot that’s the same.

If you like your fiction to be about something exceptional or extraordinary, Boyhood is decidedly the opposite. Linklater has put something of the universality of childhood on screen, however. In no way can the life of Mason Jr be interpreted as a median of everyone’s experiences, but that so much within that is so relatable shows that, however different things may appear, there’s an awful lot that’s the same.