Bow-chicka-wow-wow!

Oh, er, no, sorry — it’s not that kind of XXX. It’s Roman numerals: this is the 30th 100-Week Roundup. (But if it is the other kind of XXX that you’re looking for, check out Roundup XX.)

Still here? Lovely. So, for the uninitiated, the 100-Week Roundup covers films I still haven’t reviewed 100 weeks after watching them. Sometimes these are short ‘proper’ reviews; sometimes they’re only quick thoughts, or even just the notes I made while viewing.

That said, as with Roundup XXIX, this week has run into some reviews that I feel would be better suited placed elsewhere; mainly, franchise entries that it would be neater to pair with their sequels. Consequently, sitting out this first roundup of May 2019 viewing are The Secret Life of Pets, Jaws 2, Ice Age: The Meltdown, and Zombieland. I’m going to have to get a wriggle on with these series roundups, though, otherwise that subsection of my backlog will get out of control…

So, actually being reviewed here are…

(1999)

Stanley Kubrick | 159 mins | Blu-ray | 16:9 | UK & USA / English | 18 / R

I seem to remember Eyes Wide Shut being received poorly on its release back in 1999, but then I would’ve only been 13 at the time so perhaps I missed something. Either way, it seems to have been accepted as a great movie in the two decades since (as is the case with almost every Kubrick movie — read something into that if you like).

Numerous lengthy, analytical pieces have been written about its brilliance. This will not be one of them — my notes only include basic, ‘witty’ observations like: one minute you’re watching a “men are from Mars, woman are from Venus” kinda relationship drama, the next Tom Cruise has taken a $74.50 cab ride from Greenwich Village to an estate in the English countryside and you’re in a Hammer horror by way of David Lynch. “A Hammer horror by way of David Lynch” is a nice description, though. That sounds like my kind of film.

And Eyes Wide Shut almost is. It’s certainly a striking, intriguing, even intoxicating film, but I didn’t find the resolution to the mystery that satisfying — I wanted something more. Perhaps I should have invested more time reading those lengthy analyses — maybe then I would be giving it a full five stars. Definitely one to revisit.

Eyes Wide Shut was viewed as part of What Do You Mean You Haven’t Seen…? 2019.

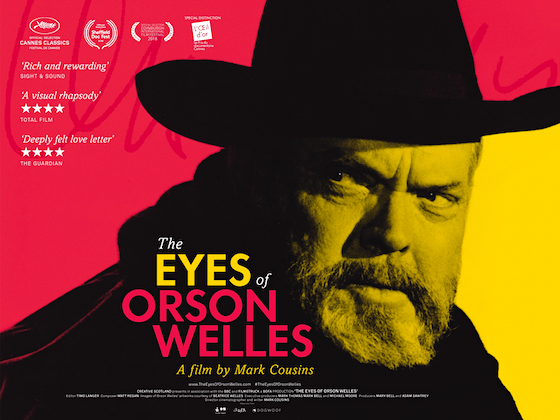

(2018)

Mark Cousins | 100 mins | TV (HD) | 16:9 | UK / English | 12

Mark Cousins, the film writer and documentarian behind the magnificent Story of Film: An Odyssey, here turns his attention to the career of one revered filmmaker: Orson Welles (obv.)

Narrated by Cousins himself, the voiceover takes the form of a letter written to Welles, which then proceeds to tell him (so it can tell us, of course) about where he went and when; about what he saw and how he interpreted it. A lot of the time it feels like it’s patronising Welles with rhetorical questions; as if Cousins is speaking to a dementia suffer who needs help to recall their own life — “Do you remember this, Orson? This is what you thought of it, isn’t it, Orson?” It makes the film quite an uneasy experience, to me; a mix of awkward and laughable.

Cousins also regularly makes pronouncements like, “you know where this is going, I’m sure,” which makes it seem like he’s constantly second-guessing himself. Perhaps it’s intended as an acknowledgement of his subject’s — his idol’s — cleverness. But it’s also presumptive: that this analysis is so obvious — so correct — that of course Welles would know where it’s going. His imagined response might be, “of course I knew where you were going, because you clearly have figured me out; you know me at least as well as I know myself.” It leaves little or no room for Welles to respond, “I disagree with that reading,” or, “I have no idea what you’re on about.” Of course, Welles can’t actually respond… but that doesn’t stop the film: near the end, Cousins has the gall to end to imagine a response from Welles, literally putting his own ideas into the man’s mouth in an act of presumptive self-validation.

I can’t deny that I learnt stuff about Orson Welles and his life from this film, but then I’ve never seen or read another comprehensive biography of the man, so that was somewhat inevitable. It’s why I give this film a passing grade, even though I found almost all of quite uncomfortable to watch.

(2016)

Richard Linklater | 112 mins | TV (HD) | 1.85:1 | USA / English | 15 / R

Everybody Wants Some Exclamation Mark Exclamation Mark (that’s how we should pronounce it, right?) is writer-director Richard Linklater’s “spiritual sequel” to his 1993 breakthrough movie, Dazed and Confused. That film has many fans (it’s even in the Criterion Collection), but I didn’t particularly care for it — I once referred to it as High Schoolers Are Dicks: The Movie. So while a lot of people were enthused for this followup’s existence, the comparison led me to put off watching it. A literal sequel might’ve shown some development with the characters ageing, but a “spiritual sequel”? That just sounds like code for “more of the same”.

And yes, in a way, this is High Schoolers Are Dicks 2: College Guys Are Also Dicks. It’s funny to me when people say movies like this are nostalgic and whatnot, because usually they just make me glad not to have to bother with all that college-age shit anymore. That said, in some respects the worst parts of the film are actually when it tries to get smart — when the characters start trying to psychoanalyse the behaviour of the group. Do I really believe college-age jocks ruminate on their own need for competitiveness, or the underlying motivations for their constant teasing and joking? No, I do not.

Still, while most of the characters are no less unlikeable than those in Dazed and Confused, I found the film itself marginally more enjoyable. These aren’t people I’d actually want to hang out with, and that’s a problem when the movie is just about hanging out with them; but, in spite of that, they are occasionally amusing, and we do occasionally get to laugh at (rather than with) them, so it’s not a total washout.

A bomb is stuck to the underside of a car. As the vehicle pulls away, the camera drifts up into the sky, and proceeds to follow the automobile through the streets of a small Mexican border town, until it crosses the border into the US… and explodes. It’s probably the most famous long take in film history, and probably the thing Touch of Evil is most widely known for; that, and it being one of the most commonly-cited points at which the classic film noir era comes to an end.

A bomb is stuck to the underside of a car. As the vehicle pulls away, the camera drifts up into the sky, and proceeds to follow the automobile through the streets of a small Mexican border town, until it crosses the border into the US… and explodes. It’s probably the most famous long take in film history, and probably the thing Touch of Evil is most widely known for; that, and it being one of the most commonly-cited points at which the classic film noir era comes to an end. It’s like a terrible fever dream, with events and characters that sometimes seem disconnected, but nonetheless interweave through a dense plot. In this sense Welles puts us quite effectively in the shoes of Vargas and his wife — out of our depth, out of our comfort zone, out of control, struggling to keep up and keep afloat. It might be unpleasant if it wasn’t so engrossing.

It’s like a terrible fever dream, with events and characters that sometimes seem disconnected, but nonetheless interweave through a dense plot. In this sense Welles puts us quite effectively in the shoes of Vargas and his wife — out of our depth, out of our comfort zone, out of control, struggling to keep up and keep afloat. It might be unpleasant if it wasn’t so engrossing. Quinlan at all… there is not the least spark of genius in him; if there does seem to be one, I’ve made a mistake.” You can get pretentious about it all you want, and bring to bear political views that the film doesn’t support (after all, within the film Quinlan is punished for his crimes and the “mediocre” (Truffaut’s word) moral hero triumphs), but sometimes a spade is a spade; sometimes a villain is a villain; sometimes your disgusting moral perspective isn’t being covertly supported by a film that seems to condemn it.

Quinlan at all… there is not the least spark of genius in him; if there does seem to be one, I’ve made a mistake.” You can get pretentious about it all you want, and bring to bear political views that the film doesn’t support (after all, within the film Quinlan is punished for his crimes and the “mediocre” (Truffaut’s word) moral hero triumphs), but sometimes a spade is a spade; sometimes a villain is a villain; sometimes your disgusting moral perspective isn’t being covertly supported by a film that seems to condemn it. Notably and obviously absent from that list is Touch of Evil. It was taken away from Welles during the editing process, and though he submitted an infamous 58-page memo of suggestions after seeing a later rough cut, only some were followed in the version ultimately released. Time has brought change, however, and there are now multiple versions of Touch of Evil for the viewer to choose from; but whereas history often resolves one version of a film to be the definitive article, it’s hard to know which that is in this case. Indeed, it’s so contentious that Masters of Cinema went so far as to include five versions on their 2011 Blu-ray (it would’ve been six, but Universal couldn’t/wouldn’t supply the final one in HD.) The version I chose to watch, dubbed the “Reconstructed Version”, tries to recreate Welles’ vision, using footage from the theatrical cut and a preview version discovered in the ’70s to follow his notes. Despite the best intentions of its creators, this can only ever be an attempt at restoring what Welles wanted. Equally, although it was the version originally released, the theatrical cut ignores many of the director’s wishes — so as neither version was finished by Welles, surely the one created by people trying to enact his wishes is preferable to the one assembled by people who only took his ideas on advisement?

Notably and obviously absent from that list is Touch of Evil. It was taken away from Welles during the editing process, and though he submitted an infamous 58-page memo of suggestions after seeing a later rough cut, only some were followed in the version ultimately released. Time has brought change, however, and there are now multiple versions of Touch of Evil for the viewer to choose from; but whereas history often resolves one version of a film to be the definitive article, it’s hard to know which that is in this case. Indeed, it’s so contentious that Masters of Cinema went so far as to include five versions on their 2011 Blu-ray (it would’ve been six, but Universal couldn’t/wouldn’t supply the final one in HD.) The version I chose to watch, dubbed the “Reconstructed Version”, tries to recreate Welles’ vision, using footage from the theatrical cut and a preview version discovered in the ’70s to follow his notes. Despite the best intentions of its creators, this can only ever be an attempt at restoring what Welles wanted. Equally, although it was the version originally released, the theatrical cut ignores many of the director’s wishes — so as neither version was finished by Welles, surely the one created by people trying to enact his wishes is preferable to the one assembled by people who only took his ideas on advisement? To quote from Master of Cinema’s booklet, “the familiar Wellesian framing appears in 1.37:1: indeed, the “world” of the film setting emerges with little or no empty space at the top and bottom of the frame, almost certainly beyond mere coincidence.” There are things to recommend the widescreen experience (“a more tightly-wound, claustrophobic atmosphere”), and undoubtedly the debate will continue… and such is the wonders of the modern film fan that, rather than having to make do with someone else’s decision on what to put out, all the alternatives are at our fingertips.

To quote from Master of Cinema’s booklet, “the familiar Wellesian framing appears in 1.37:1: indeed, the “world” of the film setting emerges with little or no empty space at the top and bottom of the frame, almost certainly beyond mere coincidence.” There are things to recommend the widescreen experience (“a more tightly-wound, claustrophobic atmosphere”), and undoubtedly the debate will continue… and such is the wonders of the modern film fan that, rather than having to make do with someone else’s decision on what to put out, all the alternatives are at our fingertips.

Remembered largely thanks to the involvement of Orson Welles (he has a supporting role, produced it, co-wrote it, and reportedly directed a fair bit too, though he denied that), Journey into Fear is an adequate if unsuspenseful World War 2 espionage thriller, redeemed by a strikingly-shot climax. The latter — a rain-drenched shoot-out between opponents edging their way around the outside of a hotel’s upper storey — was surely conducted by Welles; so too several striking compositions earlier in the movie.

Remembered largely thanks to the involvement of Orson Welles (he has a supporting role, produced it, co-wrote it, and reportedly directed a fair bit too, though he denied that), Journey into Fear is an adequate if unsuspenseful World War 2 espionage thriller, redeemed by a strikingly-shot climax. The latter — a rain-drenched shoot-out between opponents edging their way around the outside of a hotel’s upper storey — was surely conducted by Welles; so too several striking compositions earlier in the movie. all added by Welles after the studio had their way, which seems to be the one US viewers know. The version without those seems to be the only one shown on UK TV, however.)

all added by Welles after the studio had their way, which seems to be the one US viewers know. The version without those seems to be the only one shown on UK TV, however.) The Lady from Shanghai is an Orson Welles film… which means his original 155-minute cut was forcibly cut down by over an hour, the studio insisted he include more beauty shots of Rita Hayworth, as well as a song for her to sing, and the temp score he provided to the composer was ignored in favour of something Welles hated. Yet for all that — not to mention Welles’ distractingly atrocious Irish accent — it’s still a highly enjoyable film.

The Lady from Shanghai is an Orson Welles film… which means his original 155-minute cut was forcibly cut down by over an hour, the studio insisted he include more beauty shots of Rita Hayworth, as well as a song for her to sing, and the temp score he provided to the composer was ignored in favour of something Welles hated. Yet for all that — not to mention Welles’ distractingly atrocious Irish accent — it’s still a highly enjoyable film. I was meant to read Jane Eyre in the first year of my degree, but, given a week to attempt what seemed a positively enormous tome (I partly blame the edition) and a coinciding essay deadline, I didn’t even attempt it. Instead I settled for a friend summarising it for me — I tuned out halfway through the very long retelling due to boredom, though whether that was the fault of the novel or its summariser I still don’t know. I finally got through Jane Eyre the year before last — not the novel, though, but the BBC’s apparently-definitive adaptation (has it been that long already!), following numerous extremely positive reviews at the time. That was good — because or in spite of the novel, I do not know.

I was meant to read Jane Eyre in the first year of my degree, but, given a week to attempt what seemed a positively enormous tome (I partly blame the edition) and a coinciding essay deadline, I didn’t even attempt it. Instead I settled for a friend summarising it for me — I tuned out halfway through the very long retelling due to boredom, though whether that was the fault of the novel or its summariser I still don’t know. I finally got through Jane Eyre the year before last — not the novel, though, but the BBC’s apparently-definitive adaptation (has it been that long already!), following numerous extremely positive reviews at the time. That was good — because or in spite of the novel, I do not know.