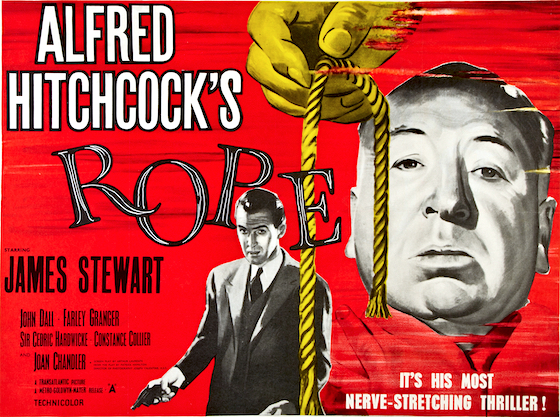

Alfred Hitchcock | 81 mins | Blu-ray | 1.33:1 | USA / English | PG / PG

Nowadays fake single takes are all over the place — some of them even last whole movies. But, as with so much cinematic trickery, it’s not actually a new idea. I don’t know if Alfred Hitchcock was the first director to attempt to trick the viewer into thinking they were watching one long take, when in fact it’s several shots stitched together via hidden cuts, but his effort is certainly one of the most famous. As an exercise in style, it’s a mixed success. Hitch is presumably inventing techniques that other filmmakers would polish and perfect in later attempts at the same stunt, but these first attempts don’t always come off perfectly. For example, every ‘hidden’ cut comes via an unmotivated camera move into the back of someone’s jacket — it may hide the cut in a literal sense, but there’s no doubting what’s going on. The entire movie is staged in actual long takes — just ten in total, most of them running seven to ten minutes. That means there are just nine cuts in the entire film, but several times (four, to be precise) Hitch just gives in and resorts to a regular cut. Sometimes you have to put the needs of the story before your showing off, I guess.

But, in other ways, the film is a great technical success. The camera moves elegantly around the apartment, employing moveable walls and stagehands shifting props while out of shot to get the moves Hitch was after. A large window at the back of the set shows a cityscape, which in other films would’ve just been a photo blowup, but here is made more convincing and alive with smoke and lights. Similarly, the passing of time is subtly emphasised because, through that window, we can see the sunlight gradually transition from daytime to evening. All of this helps sell the fact that the film takes place in real-time… sort of. Although it only runs 80 minutes, scientific analysis (yes, some scientists analyse this kind of thing) has shown the events cover about 100 minutes. Certain action is sped-up to close that gap — for example, the sun sets too quickly. Apparently this is so effective that the analysis concluded audience members feel like they’ve watched a 100-minute movie, even though it’s only 80… which, er, I don’t think was meant to sound like a criticism…

Ostensibly based on Patrick Hamilton’s play of the same name, which in turn was inspired by the Leopold and Loeb case (also the inspiration for Compulsion, amongst various other works of fiction), this adaptation changes the setting, almost all of the character names, and some of their personality traits too. Wherever they come from, the film offers an interesting array of characters. The most obvious are the two murderers — smug, cocky Brandon and worrisome Phillip — along with James Stewart, who portrays a gradual realisation that something is amis, culminating in devastation at what was really a silly thought exercise being writ into reality. Apparently Stewart thought he was miscast, but I think he’s very good, conveying much with just looks and expressions, and making you believe his moral about-turn at the end.

Other parts have, perhaps, dated: the film attracted some controversy for its homosexual overtones, but to modern eyes there’s very little to emphasise such an interpretation. Perhaps some social cues that once indicated homosexuality have fallen by the wayside in the past seven decades; or perhaps, because there’s no need to bury such things anymore, what was once ‘weird’ is now just normal behaviour. Nonetheless, much of the screenplay remains quite fun, including various nods and winks to the situation, and one slightly meta scene where two female characters talk about male movie stars they adore in front of Jimmy Stewart. But there are also sequences of familiarly Hitchcockian suspense, one great bit coming when all the characters are distracted chatting but we’re watching the maid who, while she slowly clears stuff away, is on course to discover the hidden body…

As the end credits roll, the actor who plays David — the victim, who dies in the first shot of the movie; really, no more than a prop — Is listed first, and then every other character is defined in relation to him. It’s almost like they film’s very credits are underlining the message of the film: that no one’s inferior, including David; like they’re giving him some kind of dignity in death by making him the focus of the final element of the film. It’s another neat little trick in a film that’s full of them.

Rope was viewed as part of Blindspot 2019.

Katharine Hepburn is the

Katharine Hepburn is the  Adrenaline-addicted photographer L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies (James Stewart) finds himself house- and wheelchair-bound during a New York heat wave. Whiling away time spying on his neighbours around their shared courtyard, he begins to suspect the man opposite, travelling salesman Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr), has committed a murder and is trying to cover it up. Jeff persuades his high-society girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly), visiting nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter) and police detective friend Doyle (Wendell Corey) to help investigate, but no hard evidence is forthcoming. Is Jefferies just bored and paranoid?

Adrenaline-addicted photographer L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies (James Stewart) finds himself house- and wheelchair-bound during a New York heat wave. Whiling away time spying on his neighbours around their shared courtyard, he begins to suspect the man opposite, travelling salesman Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr), has committed a murder and is trying to cover it up. Jeff persuades his high-society girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly), visiting nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter) and police detective friend Doyle (Wendell Corey) to help investigate, but no hard evidence is forthcoming. Is Jefferies just bored and paranoid? Hitchcock certainly didn’t consider Jeff to be an out-and-out hero, even aside from the very real possibility that he may be wrong — as he put it in one interview, “he’s really kind of a bastard.” After all, what right does he have to be poking his nose so thoroughly into other people’s business? Not only to spend his time spying on all and sundry, which in many respects is bad enough, but to then investigate their lives, their personal business, even break in to their homes. If he’s right, they’ve caught a murderer, and the methodology would be somewhat overlooked; if he’s wrong… well, who’s the criminal then?

Hitchcock certainly didn’t consider Jeff to be an out-and-out hero, even aside from the very real possibility that he may be wrong — as he put it in one interview, “he’s really kind of a bastard.” After all, what right does he have to be poking his nose so thoroughly into other people’s business? Not only to spend his time spying on all and sundry, which in many respects is bad enough, but to then investigate their lives, their personal business, even break in to their homes. If he’s right, they’ve caught a murderer, and the methodology would be somewhat overlooked; if he’s wrong… well, who’s the criminal then?

further enhanced by the almost total lack of a score (only present in the opening few shots).

further enhanced by the almost total lack of a score (only present in the opening few shots). Immediately after their New York Christmastime adventure in

Immediately after their New York Christmastime adventure in  There’s also an increased role for the couple’s dog, Asta, granted his own subplot as he has to fend off a philandering Scottie with intentions toward Mrs Asta. I make no apologies for preferring this over the previous film in part because there’s more amusing doggy action.

There’s also an increased role for the couple’s dog, Asta, granted his own subplot as he has to fend off a philandering Scottie with intentions toward Mrs Asta. I make no apologies for preferring this over the previous film in part because there’s more amusing doggy action. Anatomy of a Murder is a courtroom drama, adapted from a novel by a real-life defence attorney (“defense attorney”, I suppose), who in turn based his fiction on a real case. This background not only adds to the veracity of what we see, but likely explains the film’s style and structure.

Anatomy of a Murder is a courtroom drama, adapted from a novel by a real-life defence attorney (“defense attorney”, I suppose), who in turn based his fiction on a real case. This background not only adds to the veracity of what we see, but likely explains the film’s style and structure. A lot of this support is down to Stewart’s performance — it feels wrong to be cheering the defence counsel of a murderer, even if he had a justifiable motive (which, remember, he may not have) — but we’d probably cheer Stewart on if he was the murderer. His Biegler is always in control, from investigation to courtroom, even when by rights he should be completely out of it. He manipulates the judge, the prosecution, the jury and the crowd to perfection; the viewer sits by his side — we know he’s playing them so we can revel in it — but, in turn, he manipulates us too, tempting us to his team — to laugh at his jokes, to support his case, to loathe the prosecution, even though they might be right. It’s a stellar lead performance.

A lot of this support is down to Stewart’s performance — it feels wrong to be cheering the defence counsel of a murderer, even if he had a justifiable motive (which, remember, he may not have) — but we’d probably cheer Stewart on if he was the murderer. His Biegler is always in control, from investigation to courtroom, even when by rights he should be completely out of it. He manipulates the judge, the prosecution, the jury and the crowd to perfection; the viewer sits by his side — we know he’s playing them so we can revel in it — but, in turn, he manipulates us too, tempting us to his team — to laugh at his jokes, to support his case, to loathe the prosecution, even though they might be right. It’s a stellar lead performance. I could just as well go on to praise Ben Gazzara, Arthur O’Connell, Eve Arden, Brooks West, even the smaller roles occupied by Kathryn Grant, Orson Bean, Murray Hamilton and others. Some criticise Joseph N. Welch’s judge, and it’s perhaps true that his performance is a little less refined than the others, but as a slightly eccentric judge he comes off fine. And to round things off, there’s an incredibly cute dog. Mayes’ screenplay is a gift to them all, finding room for character even within the ceaselessly procedural structure, using small dashes of dialogue or passing moments to reveal and deepen each one.

I could just as well go on to praise Ben Gazzara, Arthur O’Connell, Eve Arden, Brooks West, even the smaller roles occupied by Kathryn Grant, Orson Bean, Murray Hamilton and others. Some criticise Joseph N. Welch’s judge, and it’s perhaps true that his performance is a little less refined than the others, but as a slightly eccentric judge he comes off fine. And to round things off, there’s an incredibly cute dog. Mayes’ screenplay is a gift to them all, finding room for character even within the ceaselessly procedural structure, using small dashes of dialogue or passing moments to reveal and deepen each one.