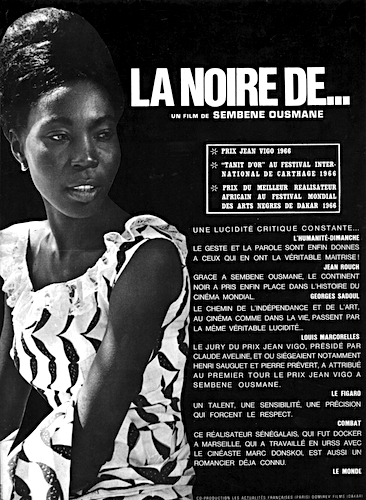

Ousmane Sembène | 59 mins | Blu-ray | 1.33:1 | Senegal & France / French | 15

Let’s be upfront about this: I’m a middle-class Western white man who herein will be critiquing a film made by a black African filmmaker about the life of a black African character. I’m stating this baldly because I wouldn’t want anyone to think I wasn’t aware of the potential connotations and pitfalls of that situation, especially as I’m about to challenge (what seems to me to be) the accepted reading of the work in question. Spoilers follow.

Believed to be the first feature film made by an indigenous black person from sub-Saharan Africa, Black Girl is the story of Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), a Senegalese women who is looking for work as a maid and finds employment babysitting the children of a French family. When they return to France, she is the only servant to travel with them; but the glamorous life on the Riviera that she’d imagined turns out to be one of drudgery, confined to the couple’s apartment, the children now nowhere to be seen.

What little I’d read about Black Girl beforehand led me to expect something about modern slavery; the eponymous black girl being mistreated by her white employers in such a way that, even though it’s the 1960s, she’s still basically a slave. Most of what I’ve read since viewing has confirmed that as the standard reading of the film. I’m not going to dispute that that’s one aspect of what’s there, but only the sum total of it if we take Diouana’s reactions and narration at face value. I mean, life in France is clearly not all she was promised; but she was looking for work as a maid and, while that wasn’t what she was doing for the family initially, the tasks they’re now asking of her don’t seem that out of step with a maid’s duties. And she gets paid for doing them. There is a period when Diouana complains (in her internal monologue) that she’s not getting paid, but the film is a little unclear on timescale — when the husband eventually gives Diouana her wages, it feels like payday has finally arrived, rather than that she’s been denied them for an unfair period of time.

Equally, there’s no denying that the wife is a demanding and demeaning bitch; and when they have some guests round for a meal, there’s the kind of casual racism that white people like to dismiss as “fun and games”, but is still degrading in its own way. So, I’m not saying Diouana is wrong to be upset with how things have turned out, but I do think the interpretation that she’s subjected to modern slavery — as opposed to just unfavourable employment — is taking things a little too far.

The key to how I interpreted the film is to realise that Diouana is more than upset — she’s depressed. Taken as a portrait of Diouana’s failing mental health, the film makes much more sense to me. Stranded in France with no one but her employers — thus, no one she can talk to honestly — her thoughts spiral round and round in her head, sinking lower, like some kind of self-fulfilling negative prophecy. It also made me wonder if we should consider Diouana an unreliable narrator. Almost the whole film is presented from her perspective, much of it via her thoughts in voiceover. So, for example, we’re told a lot about how bad her employer is before we see any sign of it; and we’re told what she was promised about France, but we never see those promises being made. Could it be she was offered to go to France, which she interpreted it as “you’ll get to see France”, but her employer never actually promised that? We don’t see the offer being made; we only have Diouana’s word for what she was promised.

Going back to my opening clarification, I appreciate that this kind of analysis might lead some to accuse me of unconscious racism — as a white person, thinking the black character might be lying and the white people are alright really, despite the evidence. But I’m not saying they are alright — they’re clearly not treating Diouana with as much humanity as she deserves — and I’m not saying she is lying, just that the film doesn’t give us hard evidence to confirm it; we only hear her memory of events. Even then, I wouldn’t say she was “lying”, just that she’d misinterpreted the situation.

Personally, that’s the only way what unfolds makes sense to me: that Diouana is misunderstanding things due to being mentally unwell. This is most relevant in how the story ends, with Diuoana taking her own life as her only route of escape — but, also, it’s the first route she takes. She doesn’t try to speak to her employers and improve her situation. Okay, maybe they wouldn’t listen, or she thinks they wouldn’t — it’s understandable not to even try under those circumstances. But she also doesn’t ask to be sent home. There’s no reason to think they wouldn’t agree to that — they’re not actually imprisoning her. They might not be pleased about it — they’ve brought her with them to do a job she was employed to do, after all — but that doesn’t mean they wouldn’t agree. Even if she thought they were holding her captive, she doesn’t attempt to escape. Sure, she’s in a foreign country and doesn’t know who to turn to — escape might not be easy — but it’s an option that doesn’t seem to cross her mind.

No, instead of any of that, she turns straight to death. As I see it, that’s the ‘logic’ of someone who’s mentally ill. That’s not someone who is merely unhappy with their situation and decides it needs to change; that’s someone who is mentally unstable and makes a bad choice. If she was genuinely enslaved — if her life was abusive and miserable and there was genuinely no other way out— then you could make an argument that, in those circumstances, taking your own life is a viable choice for escape. But that’s not the situation she’s in. Her life is not nice — it’s certainly not what she was hoping it would be — but it’s… fine? Like, other people might be content with that setup, especially if it was only temporary (we don’t know how long they’ve been in France, but the implication is weeks or a couple of months, at most; and it comes up that they might just go back to Dakar soon anyway). But instead of waiting it out, or asking to change it, or asking to leave, or running away from it, Diouana goes directly to the most final option.

Now, maybe I’m projecting a modern understanding of mental health onto the film; but the alternative (that we’re supposed to think Diouana is wholly in the right and her actions are reasonable given the circumstances) doesn’t add up for me. This also raises the question of authorial intent: was Sembène intending to explore mental health, or was he focused on racism and colonialism? I haven’t read any direct statements from him, but certainly most critics assume the latter. Normally I’m happy to write off authorial intent (“death of the author” ‘n’ all that), but I think authorship is particularly important in this case (being that it’s the first film by a black African director about the black African experience). To be honest, I don’t know for sure what he was intending — I haven’t seen any direct statements by Sembène — but the film as a whole is well-made, nicely shot and intelligently constructed (for example, using flashbacks for a nonlinear narrative), with characters who seem plausible rather than caricatures in aid of a political point. All of which is a roundabout way of saying that I think it stacks up as a psychologically-accurate depiction of someone in that situation, whether it was consciously made to be about mental health or not.

Black Girl is the 7th film in my 100 Films in a Year Challenge 2023. It was viewed as part of Blindspot 2023.

I kind of knew The Transporter Refuelled was going to be bad before I even began, but I watched it anyway because, well, I watched the

I kind of knew The Transporter Refuelled was going to be bad before I even began, but I watched it anyway because, well, I watched the  Unfortunately I wasn’t wrong about the acting, which is indeed pretty shit. Ed Skrein was truly dreadful in

Unfortunately I wasn’t wrong about the acting, which is indeed pretty shit. Ed Skrein was truly dreadful in