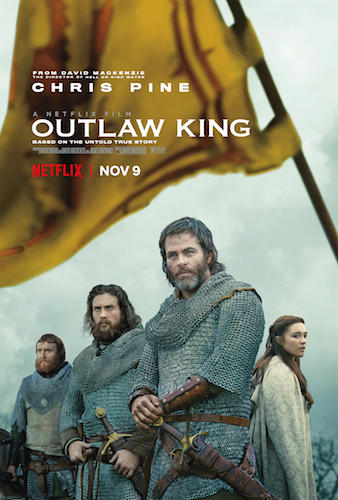

David Mackenzie | 121 mins | streaming (UHD) | 2.39:1 | UK & USA / English | 18 / R

If Netflix’s latest original movie is known for one thing, it’s for featuring a shot of Chris Pine’s penis. It’s no slight on the chap to say its appearance has generated more column inches than he possesses, though admittedly it’s hard to be certain when (penis spoilers!) it only appears for a split second in a long shot as he rises from a lake — who knows how far beneath the surface it may continue?

If the film is known for two things, the second would probably be the muted reception its premiere screening received at TIFF back in September. Director David Mackenzie scurried back to the edit suite, motivated as much by personal displeasure with how the film was playing as by the critics’ reaction, and chopped out around 20 minutes ahead of its wide Netflix debut. By the account of people who’ve seen both cuts, this has definitely improved the film’s pacing.

If the film’s known for three things, the next might actually be what it’s about. Picking up more or less where Braveheart left off, it’s the story of Scotland’s (possible) rightful king, Robert the Bruce (Chris Pine) — or, as the English king seems to keep calling him, Robert da Bruce (yo!) — and his attempt to unite the Scots and take back their land from the English (what else is new, eh?) Robert’s new English wife, Elizabeth (Florence Pugh), must decide whose side she’s on as King Edward I (Stephen Dillane) and his petulant son, the Prince of Wales (Billy Howle), employ any means necessary (with preference to brutally violent ones) to keep Scotland English.

Outlaw King kicks off in style, with a superb eight-minute single-take that moves in and out of a candle-lit tent during daytime (a feat of camera operating to seamlessly handle the changing exposures required… assuming it wasn’t faked), during which we take in important scene-setting political discussions, a playful (but not really) sword fight, and the siege of a distant castle by a gigantic trebuchet. As opening salvos go, this is first rate. The whole movie is gorgeously shot by Barry Ackroyd, in particular some stunning aerial shots of wide-open scenery — all of it genuinely Scottish, too. In terms of individual sequences though, the opener is not challenged until the climactic Battle of Loudoun Hill, a bloody, muddy, sometimes confusing (deliberately, I think) scrap between the small Scottish forces and the huge English army. How can the Scots possibly win? Tactics. I love a good medieval-style battle with proper tactics (rather than just a free-for-all of troops running at each other), and I’d say this delivers.

In between these bookends, the film is almost a Robin Hood movie: after Robert has himself crowned King of the Scots, he’s declared an outlaw, and ends up on the run with a small band of followers, which leads them to use guerrilla tactics against occupied castles. There’s also a subplot about the relationship between Robert and Elizabeth, his second wife, forced upon him by the conquering English king at the start of the film. Apparently this is one thing that’s suffered from Mackenzie’s new cut, with less time given to seeing their relationship blossom early on. It didn’t feel fatally underdeveloped to me, but it might not’ve hurt to add an extra scene (one would probably do) to help connect the dots between their initial wariness and later trusting devotion.

The overall effect doesn’t feel rousing and celebratory in the way classical historic war epics (like, of course, Braveheart) normally do, but I also don’t think that’s Mackenzie’s goal. He’s talked about endeavouring to make it reasonably historically accurate, and real-life is seldom as clear-cut and triumphant as those movies would have us believe. That said, there’s no doubting who the heroes and villains are here, with the honourable Robert trying to regain his homeland and keep his people safe, while the ineffectual Prince of Wales flounders around, all bluster and no success, slaughtering people for kicks. Boo, nasty English!

As that Robert, I thought Chris Pine made a more convincing Scotsman than Mel Gibson. I did praise the latter’s performance in my review of Braveheart, but nonetheless I never quite forgot that William Wallace was being played by American Movie Star Mel Gibson, whereas here Pine — and his (to my non-Scottish ears) perfectly passable accent — blends seamlessly with the rest of the cast. With supporting roles filled with quality performers like James Cosmo and Tony Curran, you can be assured there are no small parts. Stephan Dillane doesn’t grandstand as the villain, making him more genuinely threatening thanks to an air of calm menace, whereas Billy Howle as his son is a bit more outré, desperate to show his worthiness as heir to the throne, and failing.

Most memorable, however, is Aaron Taylor-Johnson as James Douglas. Even when the other Scottish nobles are being allowed to surrender and have their lands returned, Edward remains so disgusted by Douglas’ father’s traitorousness that he refuses to grant him the same. That makes him keen to sign up to Robert’s cause, where he’s a screamingly effective fighter. Taylor-Johnson, caked in mud and blood, wild eyed and screaming at the top of his lungs as he slaughters the English, is a sight to behold. “What’s ma fuckin’ name?” he bellows. No one’s going to forget.

Finally, a lot of praise has been reserved by others for Florence Pugh. She’s certainly a rising star, having attracted great notices in Lady Macbeth last year and currently leading the cast of the BBC’s Little Drummer Girl, but something felt off here. I don’t think it’s her fault, though. This Elizabeth feels dropped in from another time, with a very modern confidence and headstrong attitude. If Pugh was playing a woman from a few hundred years later, I’d buy it entirely, but in this setting, I’m not sure. But this is perhaps less her fault and more that of the five(!) credited screenwriters.

Another thing those scribes haven’t really included are gags. Some have criticised the film for being too serious, lacking in levity, which… I mean, have you not noticed what it’s about? I’m the first person to argue that a film about serious things doesn’t have to be 100% serious — that it’s always okay to include a variety of tones, just like real life — but it’s also okay to, well, not; to create a different experience. I don’t think Outlaw King is shooting for portentousness, which I guess is what those critics mean, but it does aim for a certain kind of intensity. After all, it’s about a small band of men trying to stand up to the greatest army in the world, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. And if Pine referring to someone as “ye cheeky wee shite” doesn’t raise a smile, well, you don’t know the Scottish well enough.

Even in its new tightened form, Outlaw King is not the outright-success Oscar-hopeful Netflix once touted it as. It’s unlikely to attain the crowd-pleasing success of Braveheart, a film that remains an obvious point of comparison but not an unreasonable one, though on balance I’d struggle to say which of the two I preferred. What this lacks in its spiritual predecessor’s grandstanding, it makes up with grit and guts (literally), making an historical war movie that frequently thrills.

Outlaw King is available on Netflix everywhere now.

Inspired by real events, The Falling stars

Inspired by real events, The Falling stars  Writer-director Carol Morley has kept the pace and tone slow, in an enchanting rather than ponderous fashion, but it’s a “not for everyone” pace nonetheless. For me, it only really lost its way as it moved into its final stages. Without wanting to spoil where it goes, in my opinion too much was explained, but at the same time it explained nothing.

Writer-director Carol Morley has kept the pace and tone slow, in an enchanting rather than ponderous fashion, but it’s a “not for everyone” pace nonetheless. For me, it only really lost its way as it moved into its final stages. Without wanting to spoil where it goes, in my opinion too much was explained, but at the same time it explained nothing. An element I do think was at the forefront of consideration is sensuality and sexuality, which plays a large and significant part in the film. Pretty much any movie bar “bawdy high school comedies starring obvious twentysomethings” seems to veer away from schoolgirl sexuality these days, wary of inevitable “OMG u a pedo” reactions, I guess. Sexuality does not equal pornography, though; and, as I alluded, here it’s played out as much through a heightened, tactile sensuality. It does probably ‘help’ that it’s a film written and directed by a woman — it would carry a very different, more Lolita-ish air if it had been written or directed by a man. What exactly it’s saying with all this is arguably as mysterious as the cause of the fainting epidemic, but then it’s all tied together: teenage years are a period of sexual awakening, of course, and if you’re in an environment where nearly everyone is of the same gender, and where such things are massively repressed… well, how is it going to manifest itself? If “sex” is somehow the cause of the fainting, it’s not because sex is bad, it’s because there’s no other appropriate outlet for it.

An element I do think was at the forefront of consideration is sensuality and sexuality, which plays a large and significant part in the film. Pretty much any movie bar “bawdy high school comedies starring obvious twentysomethings” seems to veer away from schoolgirl sexuality these days, wary of inevitable “OMG u a pedo” reactions, I guess. Sexuality does not equal pornography, though; and, as I alluded, here it’s played out as much through a heightened, tactile sensuality. It does probably ‘help’ that it’s a film written and directed by a woman — it would carry a very different, more Lolita-ish air if it had been written or directed by a man. What exactly it’s saying with all this is arguably as mysterious as the cause of the fainting epidemic, but then it’s all tied together: teenage years are a period of sexual awakening, of course, and if you’re in an environment where nearly everyone is of the same gender, and where such things are massively repressed… well, how is it going to manifest itself? If “sex” is somehow the cause of the fainting, it’s not because sex is bad, it’s because there’s no other appropriate outlet for it. Best of the lot, however, is Florence Pugh. Reportedly discovered when The Falling’s casting directors visited her school, you can see why she’s quickly been snapped up for a leading role. I wouldn’t be surprised if Hollywood come knocking looking to make her the next Kate Winslet/Keira Knightley/Gemma Arterton/etc “English rose”-type lead in some blockbuster or other.

Best of the lot, however, is Florence Pugh. Reportedly discovered when The Falling’s casting directors visited her school, you can see why she’s quickly been snapped up for a leading role. I wouldn’t be surprised if Hollywood come knocking looking to make her the next Kate Winslet/Keira Knightley/Gemma Arterton/etc “English rose”-type lead in some blockbuster or other. For me, it’s the kind of film that, with time and subconscious reflection, I may come to remember more fondly and be keen to see again, or all but forget. It’s the kind of film I could, without even re-watching it, re-evaluate and want on my year-end top ten, or could see on my top ten contenders long-list come January 1st and wonder, “dear God, what was I thinking?!” It’s the kind of film I’m not sure I wholly liked, but I’m glad I’ve seen.

For me, it’s the kind of film that, with time and subconscious reflection, I may come to remember more fondly and be keen to see again, or all but forget. It’s the kind of film I could, without even re-watching it, re-evaluate and want on my year-end top ten, or could see on my top ten contenders long-list come January 1st and wonder, “dear God, what was I thinking?!” It’s the kind of film I’m not sure I wholly liked, but I’m glad I’ve seen.