Carol Reed | 82 mins | digital (SD) | 4:3 | UK / English | U

You’ll be forgiven for not having heard of this one, even though it’s directed by Carol Reed (The Third Man, Oliver!, etc) and stars Margaret Lockwood (The Lady Vanishes, etc), because it seems to be pretty obscure. I only discovered it when browsing the online offering of UK digital channel Talking Pictures TV, and it mainly caught my attention because that was just before the weekend of the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee, when we had a double Bank Holiday. “What appropriate viewing,” I thought. Well, sometimes chance smiles on us, because this definitely doesn’t deserve to be so overlooked.

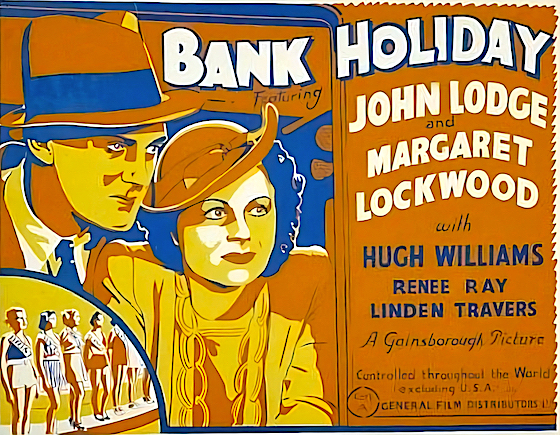

As the title indicates, the film is set on a Bank Holiday weekend — the August one, to be precise — and, this being the interwar years (i.e. well before the ease of popping overseas for a quick holiday), city folk flock to the seaside en masse. In terms of the film, a variety of melodramatic and comic plot lines unfurl for an array of characters. The primary one follows a nurse (Lockwood) getting away for a rare holiday with her young fella (Hugh Williams); but he’s not planned it very well, and she’s distracted by thoughts of a man (John Lodge) who was suddenly made a widower on her last shift. That particular storyline gets a bit heavy (death in child birth; attempted suicide), but its balanced by comic antics in other plot lines. Overall, the mix of drama and humour gives a “something for everyone”, all-round entertainment feel that you tend not to get within a single work anymore.

Nowadays, the film arguably has greatest value as a snapshot of 1930s British society. There’s a degree to which it feels ‘of its time’ as a work of cinema, but not in a terribly dated way. Indeed, while some things have changed a lot in the ensuing nine decades, but there are definitely behaviours, attitudes, and meteorological phenomena that’ll be familiar to any British viewer and their experience of a summer holiday weekend. And it remains entertaining in its own right. The comic bits still mostly work. Even when they’re not hilarious, at least they’re not embarrassing. The drama is similarly solid: the handling of romantic relationships remains relatable, rather than feeling terribly old fashioned (in fact, it had to be edited for release in the US due to its implication that an unmarried couple had a sexual relationship. And they think us Brits are the prudish ones…)

To call Bank Holiday a “forgotten classic” or similar would be to overstate the point somewhat, but it does seem to be a largely forgotten film that merits being better known.

It may be a bit of a cop out to begin a review by pointing you to another, but I must recommend

It may be a bit of a cop out to begin a review by pointing you to another, but I must recommend  Robert Newton’s Lukey. (You’ll also note Newton’s performance is criticised in Colin’s piece so, in aid of not sounding like I’m too easily influenced, I’d like to point out I didn’t make the connection between his comments and my own notes on Newton until afterwards.) Shell and Lukey have a bit of a point in the end, but I didn’t enjoy getting through them in comparison to the rest of the film.

Robert Newton’s Lukey. (You’ll also note Newton’s performance is criticised in Colin’s piece so, in aid of not sounding like I’m too easily influenced, I’d like to point out I didn’t make the connection between his comments and my own notes on Newton until afterwards.) Shell and Lukey have a bit of a point in the end, but I didn’t enjoy getting through them in comparison to the rest of the film. The score, by William Alwyn, is really nice, particularly in certain places — for example when it begins to snow and Johnny wanders the streets, or at its most effective during the haunting climax, as Kathleen hauls a near-dead Johnny through the falling snow towards the safety of the shipyard as the police finally close in.

The score, by William Alwyn, is really nice, particularly in certain places — for example when it begins to snow and Johnny wanders the streets, or at its most effective during the haunting climax, as Kathleen hauls a near-dead Johnny through the falling snow towards the safety of the shipyard as the police finally close in.