Isao Takahata | 90 mins | DVD | 16:9 | Japan / Japanese | 12

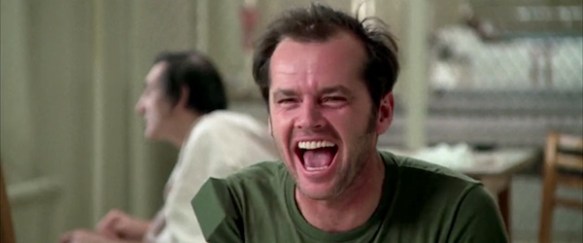

One of the most praised animated films of all time, this Studio Ghibli feature tackles grim subject matter: it’s the story of Seita and his little sister Setsuko, a pair of Japanese children who are orphaned and eventually left to fend for themselves in the closing months of World War 2. It begins with Seita dying of starvation and joining the spirit of his dead sister, so you know it’s not going to end well. A Disney movie this is not.

One of the most praised animated films of all time, this Studio Ghibli feature tackles grim subject matter: it’s the story of Seita and his little sister Setsuko, a pair of Japanese children who are orphaned and eventually left to fend for themselves in the closing months of World War 2. It begins with Seita dying of starvation and joining the spirit of his dead sister, so you know it’s not going to end well. A Disney movie this is not.

It’s kind of hard to avoid the praise Grave of the Fireflies has attracted, which is why it ended up on my Blindspot list this year. It’s the third highest-rated animation on IMDb (behind Spirited Away and The Lion King), which also places it in the top 25% of the Top 250, not to mention various other “best animated” and “great movie” lists. I mention all this because I fear the weight of expectation somewhat hampered the film for me. It’s by no means a bad film, but, despite the subject matter, it didn’t touch me to the same degree as, say, My Neighbour Totoro (which, coincidentally, it was initially released with).

So where did it go wrong for me? Perhaps my biggest issue was with Seita and the choices he made. I guess part of the point is that he is still a child and so unable to adequately care for himself and Setsuko, but I don’t get why he resorts to stealing, looting, and allowing them to starve when, as it eventually turns out, they still have 3,000 yen in the bank — enough to buy plenty of hearty food when it comes down to it. Why didn’t he turn to that money much sooner? Why did it take a doctor telling him his sister was malnourished and refusing to help before he thought, “you know what, I could always use that money we have saved up in the bank to feed us so I don’t have to steal and nonetheless be short of food”? When he does eventually withdraw that cash and buy some decent supplies, it’s a very literal case of doing too little too late.

Another thing is that the film is often cited as a powerful anti-war movie, because it depicts the ravaging effects on innocents. However, director Isao Takahata insists it isn’t, saying it’s about “the brother and sister living a failed life due to isolation from society”. I’m inclined to believe him, because, from what we actually see on screen, these two kids are the only ones to be so badly affected! Okay, we do see people have died, and we’re told that food is running out… but there’s a gaggle of kids who seem to be having a fun day out when they stumble across the siblings’ makeshift shelter; or, right at the end, people who merrily arrive home and pop their music on. The film doesn’t try to claim that only these two kids suffered, but — aside from a few other destitutes at the start, and the bodies we see after the first bombing (later bombings don’t make any casualties explicit) — we don’t really see anyone else suffering. I’m not arguing that Takahata is saying no one else suffered, nor that these observations make it pro-war (I mean, any children dying, even if others are surviving, is not a good thing), but I didn’t get an anti-war message that was as powerful or as overwhelming as other viewers seem to have.

Another thing is that the film is often cited as a powerful anti-war movie, because it depicts the ravaging effects on innocents. However, director Isao Takahata insists it isn’t, saying it’s about “the brother and sister living a failed life due to isolation from society”. I’m inclined to believe him, because, from what we actually see on screen, these two kids are the only ones to be so badly affected! Okay, we do see people have died, and we’re told that food is running out… but there’s a gaggle of kids who seem to be having a fun day out when they stumble across the siblings’ makeshift shelter; or, right at the end, people who merrily arrive home and pop their music on. The film doesn’t try to claim that only these two kids suffered, but — aside from a few other destitutes at the start, and the bodies we see after the first bombing (later bombings don’t make any casualties explicit) — we don’t really see anyone else suffering. I’m not arguing that Takahata is saying no one else suffered, nor that these observations make it pro-war (I mean, any children dying, even if others are surviving, is not a good thing), but I didn’t get an anti-war message that was as powerful or as overwhelming as other viewers seem to have.

I’m an advocate of animation as a form (which must sound like a ridiculous position to have to take in some countries, but in the West “quality animation” begins and ends with Disney musicals and Pixar’s kid-friendly comedy adventures), but I think the fact this particular story is being told with moving drawings is detrimental. I’ve seen online reviews that say it makes the film more bearable because it creates a kind of disconnect from the real world —  and, really, this story shouldn’t be “bearable”. That’s not to say you can’t feel an emotional connection to animated characters, but, as a medium, animation regularly deals in fantastical subjects, so with material this gruelling it does make it seem less real.

and, really, this story shouldn’t be “bearable”. That’s not to say you can’t feel an emotional connection to animated characters, but, as a medium, animation regularly deals in fantastical subjects, so with material this gruelling it does make it seem less real.

Despite these issues, Grave of the Fireflies does still pack a punch, but I wasn’t as bowled over as I’d expected to be.

Grave of the Fireflies was viewed as part of my What Do You Mean You Haven’t Seen…? 2016 project, which you can read more about here.

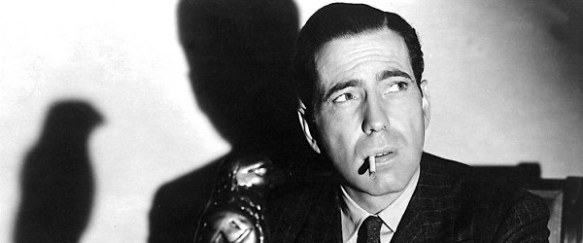

Stanley Kubrick made a good many exceptionally well-regarded films — indeed, with possibly the exception of his first semi-amateur feature,

Stanley Kubrick made a good many exceptionally well-regarded films — indeed, with possibly the exception of his first semi-amateur feature,  who often tells us less-than-favourable things about the lead character. Apparently this is an example of an unreliable narrator, and I suppose some of the things we’re told aren’t directly evidenced on screen, but I’m afraid I’m going to have to leave that seam to be mined by other writers, because (on a first viewing at least) I didn’t see where or to what effect the narrator was lying to the viewer.

who often tells us less-than-favourable things about the lead character. Apparently this is an example of an unreliable narrator, and I suppose some of the things we’re told aren’t directly evidenced on screen, but I’m afraid I’m going to have to leave that seam to be mined by other writers, because (on a first viewing at least) I didn’t see where or to what effect the narrator was lying to the viewer. but a fictional biopic, that ranges across Europe and across time to… what effect? It’s a Kubrick film, so the ultimate goal of the tale, the message(s) it may be trying to impart, are debatable. You could see a story of the pitfalls of hubris. You could see an exploration of how a certain class lived in this time period. You could just see a man who led an adventurous life.

but a fictional biopic, that ranges across Europe and across time to… what effect? It’s a Kubrick film, so the ultimate goal of the tale, the message(s) it may be trying to impart, are debatable. You could see a story of the pitfalls of hubris. You could see an exploration of how a certain class lived in this time period. You could just see a man who led an adventurous life. just that it remains the best among greats. (That said, having looked up images online for this review, it seems slightly less striking to me now. That may be the quality of the screengrabs; it may be that the painterly quality is so remarkable at first appearance (before becoming more familiar when the whole movie has that quality) that its memorableness is heightened.)

just that it remains the best among greats. (That said, having looked up images online for this review, it seems slightly less striking to me now. That may be the quality of the screengrabs; it may be that the painterly quality is so remarkable at first appearance (before becoming more familiar when the whole movie has that quality) that its memorableness is heightened.)

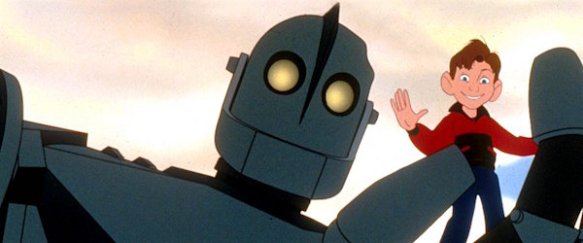

Adapted (loosely) from Ted Hughes’ children’s novel The Iron Man, the feature debut of director Brad Bird (

Adapted (loosely) from Ted Hughes’ children’s novel The Iron Man, the feature debut of director Brad Bird ( The story, as reconstructed by Bird and screenwriter Tim McCanlies, integrates influences from ’50s B-movies (very apt for a giant robot ‘monster’) and Cold War/Space Race paranoia for a potent storyline that has a different emphasis from the novel’s “world peace” finale, but nonetheless is promoting understanding of alien/foreign powers and, y’know, deep stuff like that. Alternatively — or, rather, concurrently — it’s an

The story, as reconstructed by Bird and screenwriter Tim McCanlies, integrates influences from ’50s B-movies (very apt for a giant robot ‘monster’) and Cold War/Space Race paranoia for a potent storyline that has a different emphasis from the novel’s “world peace” finale, but nonetheless is promoting understanding of alien/foreign powers and, y’know, deep stuff like that. Alternatively — or, rather, concurrently — it’s an  reputation it has gradually amassed — and which only continues to grow, I think. Last year saw the release of an extended Signature Edition, with a couple of short scenes added, which comes to US Blu-ray (alongside the original version) later this year. Just from reading about those new scenes, I’m not convinced they’ll improve the experience, but it’ll certainly be worth finding out.

reputation it has gradually amassed — and which only continues to grow, I think. Last year saw the release of an extended Signature Edition, with a couple of short scenes added, which comes to US Blu-ray (alongside the original version) later this year. Just from reading about those new scenes, I’m not convinced they’ll improve the experience, but it’ll certainly be worth finding out.