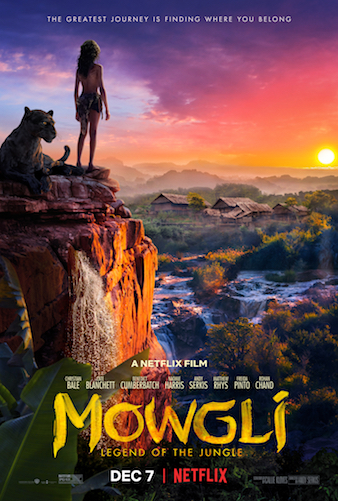

Andy Serkis | 104 mins | streaming (HD) | 2.39:1 | UK & USA / English & Hindi | 12 / PG-13

Hollywood has a long history of different people coming up with the same idea resulting in competing films — asteroid-themed Armageddon and Deep Impact is perhaps the best-known example. But often when the ideas are too similar, one of the projects gets scrapped — Baz Luhrmann ditched plans for an Alexander the Great biopic once Oliver Stone’s got underway, for instance. When Disney and Warner Bros both announced CGI-driven live-action adaptations of Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, I don’t know about anyone else, but I figured one studio would blink and we’d end up with just one film. That didn’t happen, and both movies entered production around the same time, and were even originally scheduled to come out the same year. In this respect it was Warner who blinked first, putting their version back to allow more time to finesse the motion-capture-driven animation, while Disney got theirs out on schedule. Unfortunately for Warner, it was a huge hit with critics and audiences alike, putting their version in a rather precarious position.

So when the news broke that Mowgli (as the film had been retitled to help distance it from Disney’s) was to be released direct to Netflix, well, I don’t think anyone was surprised: the streaming service has become a regular dumping ground for movies that studios have lost confidence in, seemingly happy to pay for any castoff a major studio throws their way. Apparently that’s not what went down this time, though: Mowgli had a theatrical release date set and the promotional campaign had begun, when Netflix approached Warner saying they loved the film and wanted to buy it. I guess the certainty of a large Netflix payday vs. the gamble of box office success on a film that could be seen by the general public as a Johnny-come-lately cash-in rip-off was an easy choice for Warner to make. And so here we are.

Mowgli (as it’s always called in the film itself, the subtitle presumably being a Netflix marketing addition) has a story that will be broadly familiar to anyone who’s seen any other version of The Jungle Book, most especially that recent Disney one: the eponymous boy is orphaned when his parents are murdered by man-eating tiger Shere Khan, but he’s rescued by black panther Bagheera, who takes him to be raised by a pack of wolves. Shere Khan wants to kill the man-cub, however, and looks for an opportunity to separate him from the wolves’ protection. The difference, then, lies in the details: where Disney’s version was PG-rated and family-friendly, director Andy Serkis has given this a darker, PG-13 spin. It’s not an Adult movie by any means, but it’s definitely suited to slightly older children. That said, there’s a revelation at the 80-minute mark which is horrendously misjudged, and is liable to upset children of all ages (i.e. including some adults too).

That moment aside, the film’s more realistic tone manifests in multiple ways. One is characterisation, most notably of the bear Baloo. As we know him from Disney’s takes, he’s decidedly laid-back and chummy, casually teaching Mowgli some ways of the jungle. Here, he’s more of a drill sergeant for the wolf pack, explicitly training Mowgli (and his wolf brothers) in the skills required to fully join the pack. He has a softer side — he definitely cares for the man-cub — but this never manifests in the Disney-ish way. Elsewhere, there’s a drive at some kind of psychological realism for our hero. With Mowgli driven out for his own safety (again, an example of the animal characters being somewhat harsher than in Disney), he ends up in a human village. There, he comes to realise he doesn’t truly belong in the world of animals… but nor does he truly belong in the world of men. This internal conflict about his place in the world comes to underpin the climax, and arguably makes it superior to the over-elaborate forest-fire spectacle of Disney’s film.

The realism extends to the overall visual style, too. Where Disney’s live-action version was all shot on L.A. sound stages, with the young actor playing Mowgli frequently the only real thing on screen, Serkis and co travelled overseas and actually built sets on location to shoot a significant portion of the film. Accompanied by cinematography that often goes for a muted colour palette, it seems clear the aim was to make a film that is perhaps not “darker” in the now-somewhat-clichéd sense, but more grounded and less cartoonish than certain other adaptations.

Unfortunately, Serkis made one design decision that threatens to scupper the entire endeavour: having motion-captured famous actors for most of the animal roles (including the likes of Christian Bale, Benedict Cumberbatch, Cate Blanchett, Tom Hollander, Peter Mullan, Eddie Marsan, Naomie Harris, and, of course, Serkis himself), someone thought it would be a good idea to try to integrate the actors’ features into the animal faces. The result is… disturbing. There’s so much realism in the overall design, but then they have these faces that are part realistic, part cartoon, part like some kind of grotesque prosthetic. It is so bad that it genuinely undermines the entire movie, for two reasons: one, it’s a distraction, making you constantly try to parse what you’re watching and how you feel about it; and two, a more serious take on the material asks for us to make a more serious connection to the characters, and that’s hard when they look so horrid. The section in the human village — which, by rights, should be “the boring bit” because it doesn’t involve fun animal action — is probably the film’s strongest thanks to its location photography and real actors making it so much more tangible. It suggests how much more likeable the entire film would be if they’d gone for real-world-ish animal designs — like, ironically, the Disney film did. (Now, that might’ve got away with cartoonish semi-human animals thanks to its lighter tone. Or it might not, because these are monstrous.)

It sounds petty to pick one highly specific element and say it ruins the film, but I really felt like it did. It’s a barrier to enjoying the bits that work (Rohan Chand is often superb as Mowgli; the always-brilliant Matthew Rhys is brilliant as always; there’s some welcome complexity and nuance to several characters and situations), and therefore it does nothing to help gloss over any other nits you want to pick (Serkis is miscast; Frieda Pinto is completely wasted; Cumberbatch is a little bit Smaug Mk.II; that revelation I mentioned back in paragraph three is brutal and I can’t believe it was okayed by the studio). Also, on a somewhat personal note, I felt there were times you could tell Serkis had made the film in 3D, but Netflix haven’t bothered to release it in that format (outside of some very limited theatrical screenings) — as someone who owns a 3D TV because, you know, I enjoy it, that miffed me.

On the whole, Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle is a frustratingly imperfect experience. I believe it’s fundamentally a unique-enough variation on the material that it could’ve escaped the shadow of Disney’s film, but a few misguided creative decisions have dragged it down almost irreparably.

Mowgli is available on Netflix worldwide now.

2016 Academy Awards

2016 Academy Awards Star Wars: The Force Awakens is not the best film of 2015. Not according to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, anyway, who didn’t see fit to nominate it for Best Picture at tomorrow’s Oscars. Many fans disagree, some vociferously, but was it really a surprise? The Force Awakens is a blockbuster entertainment of the kind the Academy rarely recognise. Okay, sci-fi actioner

Star Wars: The Force Awakens is not the best film of 2015. Not according to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, anyway, who didn’t see fit to nominate it for Best Picture at tomorrow’s Oscars. Many fans disagree, some vociferously, but was it really a surprise? The Force Awakens is a blockbuster entertainment of the kind the Academy rarely recognise. Okay, sci-fi actioner  I too could talk about the likeable new heroes; the triumphant return of old favourites; the underuse of other old favourites; Daisy Ridley’s performance; John Boyega’s performance; the relationship between Rey and Finn; the relationship between Finn and Poe; the success of Kylo Ren and General Hux as villains (well, I thought they were good); the terrible CGI of Supreme Leader Snoke; the ridiculous overreaction to the alleged underuse of Captain Phasma; that awesome fight between the stormtrooper with that lightning stick thing and Finn with the lightsaber; the mystery of Rey’s parentage; the mystery of who Max von Sydow was meant to be (and if we’ll ever find out); some elaborate theory about why Ben wasn’t called Jacen (there must be one — elaborate theories that will never be canon are what fandoms are good for); the way it accurately emulates the classic trilogy’s tone; the way it’s basically a remake of

I too could talk about the likeable new heroes; the triumphant return of old favourites; the underuse of other old favourites; Daisy Ridley’s performance; John Boyega’s performance; the relationship between Rey and Finn; the relationship between Finn and Poe; the success of Kylo Ren and General Hux as villains (well, I thought they were good); the terrible CGI of Supreme Leader Snoke; the ridiculous overreaction to the alleged underuse of Captain Phasma; that awesome fight between the stormtrooper with that lightning stick thing and Finn with the lightsaber; the mystery of Rey’s parentage; the mystery of who Max von Sydow was meant to be (and if we’ll ever find out); some elaborate theory about why Ben wasn’t called Jacen (there must be one — elaborate theories that will never be canon are what fandoms are good for); the way it accurately emulates the classic trilogy’s tone; the way it’s basically a remake of

J.J. Abrams seems to have tricked some people into thinking he’s a great director with The Force Awakens (rather than just a helmer of workmanlike adequacy (when he’s not indulging his lens flare obsession, at which point he’s not workmanlike but is inadequate)), and I think that’s partly because it’s quite classically made. Yeah, it’s in 3D, but the style of shots used and — of most relevance right now — the pace of the editing help it feel in line with the previous Star Wars movies. Some of the more outrageous shots (often during action sequences) stand out precisely because they’re outside this norm. Perhaps we take for granted that Abrams delivered a movie in keeping with the rest of the series, because that’s The Right Thing To Do, but that doesn’t mean he had to do it. And the transitional wipes are there too, of course.

J.J. Abrams seems to have tricked some people into thinking he’s a great director with The Force Awakens (rather than just a helmer of workmanlike adequacy (when he’s not indulging his lens flare obsession, at which point he’s not workmanlike but is inadequate)), and I think that’s partly because it’s quite classically made. Yeah, it’s in 3D, but the style of shots used and — of most relevance right now — the pace of the editing help it feel in line with the previous Star Wars movies. Some of the more outrageous shots (often during action sequences) stand out precisely because they’re outside this norm. Perhaps we take for granted that Abrams delivered a movie in keeping with the rest of the series, because that’s The Right Thing To Do, but that doesn’t mean he had to do it. And the transitional wipes are there too, of course. No one knows what the difference is between these two categories. I’m not even sure that people who work in the industry know. As a layperson, it’s also the kind of thing you tend to only notice when it’s been done badly. The Force Awakens’ sound was not bad. It all sounded suitably Star Wars-y, as far as I could tell. That’s about all I could say for it. It feels like these are categories that get won either, a) on a sweep, or b) on a whim, so who knows who’ll take them on the night?

No one knows what the difference is between these two categories. I’m not even sure that people who work in the industry know. As a layperson, it’s also the kind of thing you tend to only notice when it’s been done badly. The Force Awakens’ sound was not bad. It all sounded suitably Star Wars-y, as far as I could tell. That’s about all I could say for it. It feels like these are categories that get won either, a) on a sweep, or b) on a whim, so who knows who’ll take them on the night? “restraint […] applying the basic filmmaking lessons of the first trilogy,” according to

“restraint […] applying the basic filmmaking lessons of the first trilogy,” according to  those elements aren’t gone about in an awards-grabbing fashion anyway. In the name of blockbuster entertainment, however, they’re all highly accomplished.

those elements aren’t gone about in an awards-grabbing fashion anyway. In the name of blockbuster entertainment, however, they’re all highly accomplished. It feels kind of pointless reviewing Avengers: Age of Ultron, the written-and-directed-by Joss Whedon (and, infamously, reshaped-in-the-edit-by committee) follow-up to 2012’s “third most successful film of all time” mega-hit

It feels kind of pointless reviewing Avengers: Age of Ultron, the written-and-directed-by Joss Whedon (and, infamously, reshaped-in-the-edit-by committee) follow-up to 2012’s “third most successful film of all time” mega-hit  Even though the first half of that is still three years away, we’re still very much on the road to it. Heck, we have been practically since the MCU began, thanks to those frickin’ stones (if you don’t know already, don’t expect me to explain it to you), but now it’s overt as well as laid in fan-friendly easter eggs. The titular threat may rise and be put down within the confines of Age of Ultron’s near-two-and-a-half-hour running time, but no such kindness is afforded to the myriad subplots.

Even though the first half of that is still three years away, we’re still very much on the road to it. Heck, we have been practically since the MCU began, thanks to those frickin’ stones (if you don’t know already, don’t expect me to explain it to you), but now it’s overt as well as laid in fan-friendly easter eggs. The titular threat may rise and be put down within the confines of Age of Ultron’s near-two-and-a-half-hour running time, but no such kindness is afforded to the myriad subplots. (not just obvious stuff like the Hulk, but digital set extensions, fake location work, even modifying Stark’s normal Audi on a normal road because it was a future model that wasn’t physically built when filming) that stuff they genuinely did for real looks computer generated too. All that time, all that effort, all that epic logistical nightmare stuff like shutting down a capital city’s major roads for several days… and everyone’s going to assume some tech guys did it in an office, because that’s what it looks like. If you’re going to go to so much trouble to do it for real, make sure it still looks real by the time you get to the final cut. I’ll give you one specific example: Black Widow weaving through traffic on a motorbike in Seoul. I thought it was one of the film’s less-polished effects shots. Nope — done for real, and at great difficulty because it’s tough to pull off a fast-moving bike speeding through fast-moving cars. What a waste of effort!

(not just obvious stuff like the Hulk, but digital set extensions, fake location work, even modifying Stark’s normal Audi on a normal road because it was a future model that wasn’t physically built when filming) that stuff they genuinely did for real looks computer generated too. All that time, all that effort, all that epic logistical nightmare stuff like shutting down a capital city’s major roads for several days… and everyone’s going to assume some tech guys did it in an office, because that’s what it looks like. If you’re going to go to so much trouble to do it for real, make sure it still looks real by the time you get to the final cut. I’ll give you one specific example: Black Widow weaving through traffic on a motorbike in Seoul. I thought it was one of the film’s less-polished effects shots. Nope — done for real, and at great difficulty because it’s tough to pull off a fast-moving bike speeding through fast-moving cars. What a waste of effort! The really daft thing is, Whedon specifically added Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver… wait, are Marvel allowed to call them that? I forget. Anyway, Whedon added the Maximoff twins because, as he said himself, “their powers are very visually interesting. One of the problems I had on the first one was everybody basically had punchy powers.” I know Hawkeye’s power is more shoot-y than punchy, and we all know

The really daft thing is, Whedon specifically added Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver… wait, are Marvel allowed to call them that? I forget. Anyway, Whedon added the Maximoff twins because, as he said himself, “their powers are very visually interesting. One of the problems I had on the first one was everybody basically had punchy powers.” I know Hawkeye’s power is more shoot-y than punchy, and we all know  At the end of the day, what does it matter? Age of Ultron isn’t so remarkably good — nor did it go down so remarkably poorly — that it deserves a reevaluation someday. It just is what it is: an overstuffed superhero epic, which has too much to do to be able to compete with its comparatively-simple contributing films on quality grounds, but is entertaining enough as fast-food cinema. Blockbusterdom certainly has worse experiences to offer.

At the end of the day, what does it matter? Age of Ultron isn’t so remarkably good — nor did it go down so remarkably poorly — that it deserves a reevaluation someday. It just is what it is: an overstuffed superhero epic, which has too much to do to be able to compete with its comparatively-simple contributing films on quality grounds, but is entertaining enough as fast-food cinema. Blockbusterdom certainly has worse experiences to offer.

1981: Steven Spielberg reads a French review of his movie

1981: Steven Spielberg reads a French review of his movie  Apparently some Tintin purists weren’t so keen on the actual adaptation — elements of The Crab with the Golden Claws have been mixed in to a plot primarily taken from The Secret of the Unicorn, the sequel/second half of which, Red Rackham’s Treasure, is reportedly used sparingly. Plus, in the original tale Sakharine is a minor character who wasn’t responsible for much, apparently. As someone who’s only read one of those three volumes, and even then not since I was young, such things didn’t trouble me. What superstar screenwriters Steven “

Apparently some Tintin purists weren’t so keen on the actual adaptation — elements of The Crab with the Golden Claws have been mixed in to a plot primarily taken from The Secret of the Unicorn, the sequel/second half of which, Red Rackham’s Treasure, is reportedly used sparingly. Plus, in the original tale Sakharine is a minor character who wasn’t responsible for much, apparently. As someone who’s only read one of those three volumes, and even then not since I was young, such things didn’t trouble me. What superstar screenwriters Steven “ The slapstick is mainly hoisted by Simon Pegg and Nick Frost as the physically-identical Thomson and Thompson — a true advantage of animation, that. I imagine some find their parts tiresome because of their inherently comic role, but they’re likeable versions of the characters. Even more joyous is Snowy, though. Well, I would like him, wouldn’t I? His internal monologue, such a memorable part of Hergé’s books, is omitted (as it is from every film version to date, I believe), but he’s full of character nonetheless. Some of the best sequences involve Snowy running in to save the day. I don’t think they quite got the animation model right (the one glimpsed in test footage included in behind-the-scenes featurettes looks better, for my money), but his characterisation overcomes that.

The slapstick is mainly hoisted by Simon Pegg and Nick Frost as the physically-identical Thomson and Thompson — a true advantage of animation, that. I imagine some find their parts tiresome because of their inherently comic role, but they’re likeable versions of the characters. Even more joyous is Snowy, though. Well, I would like him, wouldn’t I? His internal monologue, such a memorable part of Hergé’s books, is omitted (as it is from every film version to date, I believe), but he’s full of character nonetheless. Some of the best sequences involve Snowy running in to save the day. I don’t think they quite got the animation model right (the one glimpsed in test footage included in behind-the-scenes featurettes looks better, for my money), but his characterisation overcomes that. Of course, one very important person is neither British nor Belgian: Spielberg. The screenplay’s balance between peril and comedy is spotlessly enhanced by his peerless direction. In a world stuffed to the gills with lesser blockbusters that palely imitate the groundwork Spielberg and co laid in the ’70s and ’80s, work like this should remind people why he’s still the master of the form. The film is shot with an eye for realism (so much so that some viewers have been convinced it was filmed on real locations with real actors, with some CG augmentation for the cartoonish faces, of course), which helps lend a sense of plausibility and also genuine jeopardy. It’s easy to get carried away when working in CG animation, but often the most impressive works are ones that behave as if they’ve been shot largely within the limitations of real-world filmmaking technology.

Of course, one very important person is neither British nor Belgian: Spielberg. The screenplay’s balance between peril and comedy is spotlessly enhanced by his peerless direction. In a world stuffed to the gills with lesser blockbusters that palely imitate the groundwork Spielberg and co laid in the ’70s and ’80s, work like this should remind people why he’s still the master of the form. The film is shot with an eye for realism (so much so that some viewers have been convinced it was filmed on real locations with real actors, with some CG augmentation for the cartoonish faces, of course), which helps lend a sense of plausibility and also genuine jeopardy. It’s easy to get carried away when working in CG animation, but often the most impressive works are ones that behave as if they’ve been shot largely within the limitations of real-world filmmaking technology. The tone on the whole is resolutely PG — actually, like many an action-adventure blockbuster used to be before everything went slightly darker and PG-13. So, for example, Tintin wields a gun on occasion, but never at another human being. The focus is on the story, which happens to lead to some adrenaline-pumping sequences, rather than a lightweight excuse to link together a bunch of punch-ups and chases. Ironically (though, for anyone who knows what they’re talking about, entirely expectedly) this makes the action all the more exciting. It also mean there’s a lighter touch than many current blockbusters offer; a greater presence for humour, including among the action. I guess that’s not fashionable these days, when everyone’s become so po-faced about their big-budget entertainment. However, with the likes of

The tone on the whole is resolutely PG — actually, like many an action-adventure blockbuster used to be before everything went slightly darker and PG-13. So, for example, Tintin wields a gun on occasion, but never at another human being. The focus is on the story, which happens to lead to some adrenaline-pumping sequences, rather than a lightweight excuse to link together a bunch of punch-ups and chases. Ironically (though, for anyone who knows what they’re talking about, entirely expectedly) this makes the action all the more exciting. It also mean there’s a lighter touch than many current blockbusters offer; a greater presence for humour, including among the action. I guess that’s not fashionable these days, when everyone’s become so po-faced about their big-budget entertainment. However, with the likes of  but some viewers would have seen it (even subconsciously) as more of a “real movie”.

but some viewers would have seen it (even subconsciously) as more of a “real movie”.

A heady mix of solid writing from Mark Bomback, Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver, peerless motion-captured performances from the likes of Serkis and Toby Kebbell, and first-rate CG magic from Weta, brings us a set of characters who are compelling and believable. Here is a society trying to define what it wants to be, battling old prejudices in the hope of a peaceful, secure, happy future. If you want to draw analogies to almost any real-world political situation, I’m sure you could.

A heady mix of solid writing from Mark Bomback, Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver, peerless motion-captured performances from the likes of Serkis and Toby Kebbell, and first-rate CG magic from Weta, brings us a set of characters who are compelling and believable. Here is a society trying to define what it wants to be, battling old prejudices in the hope of a peaceful, secure, happy future. If you want to draw analogies to almost any real-world political situation, I’m sure you could. Lest you get the wrong impression, the film isn’t all talk. For various spoiler-y reasons, the fragile relationship between Man and Ape breaks down, and the apes stage an attack on humanity. Here we get perhaps one of the best siege action sequences I can think of, with mankind holed up in a half-constructed skyscraper that sits conveniently at the end of a long street for the apes to charge down. Reeves’ direction is virtuosic here, crafting an epic and exciting sequence even when most of the film’s major players are busy elsewhere. And it’s not even the climax.

Lest you get the wrong impression, the film isn’t all talk. For various spoiler-y reasons, the fragile relationship between Man and Ape breaks down, and the apes stage an attack on humanity. Here we get perhaps one of the best siege action sequences I can think of, with mankind holed up in a half-constructed skyscraper that sits conveniently at the end of a long street for the apes to charge down. Reeves’ direction is virtuosic here, crafting an epic and exciting sequence even when most of the film’s major players are busy elsewhere. And it’s not even the climax. thanks to some surprisingly small-scale narrative choices (the whole thing with the dam doesn’t feel nearly as vital as it should) and Reeves’ direction sometimes being a little straightforward and almost TV-ish. I know I’ve said I hate when people use that as a derogatory comment nowadays, but some repeated locations and shot choices make the film feel cheaper than it was.

thanks to some surprisingly small-scale narrative choices (the whole thing with the dam doesn’t feel nearly as vital as it should) and Reeves’ direction sometimes being a little straightforward and almost TV-ish. I know I’ve said I hate when people use that as a derogatory comment nowadays, but some repeated locations and shot choices make the film feel cheaper than it was. Aardman Animations, the Bristol-based company most famous for

Aardman Animations, the Bristol-based company most famous for  The latest effort from the director of

The latest effort from the director of