Regular readers may be aware that for a while now I’ve been struggling with what to do about my increasingly ludicrous review backlog. It continues to grow and grow — it’s now reached a whopping 215 unreviewed films! (And to think I started that page because I was 10 reviews behind…) Realistically, there’s no way I’m ever going to catch that up just by posting normal reviews, especially given the rate I get them out nowadays. But since this blog began I’ve reviewed every new film I watched — I don’t want to break that streak.

So, I’ve come up with something of a solution — and kept it broadly within the theming of the blog, to boot.

The 100-Week Roundup will cover films I still haven’t reviewed 100 weeks after watching them. Most of the time that’ll be in the form of quick thoughts, perhaps even copy-and-pasting the notes I made while viewing, rather than ‘proper’ reviews. Today’s are a bit more review-like, but relatively light on worthwhile analytical content, which I think is another reason films might end up here. Also, the posts won’t be slavishly precise in their 100-week-ness. Instead, I’ll ensure there are at least a couple of films covered in each roundup (it wouldn’t be a “roundup” otherwise). Mainly, the point is to give me a cutoff to get a review done — if I want to avoid a film being swept up into a roundup, I’ve got 100 weeks to review it. (Lest we forget, 100 weeks is almost two years. A more-than-generous allowance.)

I think it’s going to start slow (this first edition covers everything I haven’t reviewed from April 2018, which totals just two films), but in years to come I wouldn’t be surprised if these roundups become more frequent and/or busier. But, for now, those two from almost two years ago…

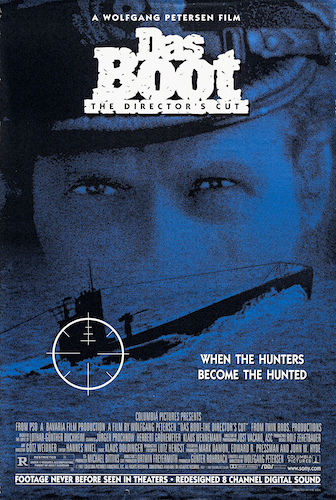

Das Boot

The Director’s Cut

(1981/1997)

2018 #69

Wolfgang Petersen | 208 mins | Blu-ray | 1.85:1 | Germany & USA / German & English | 15 / R

Writer-director Wolfgang Petersen’s story of a German submarine in World War 2 may have an intimate and confined setting, but in every other sense it is an epic — not least in length: The Director’s Cut version runs almost three-and-a-half hours. However, the pace is excellently managed. The length is mainly used for tension — quietly waiting to see if the enemy will get them this time. It’s also spent getting to know some of the crew, and the style of life aboard the sub. It means the film paints an all-round picture of both life and combat in that situation. The only time I felt it dragged was in an extended sequence towards the end. I guess the long, slow shots of nothing happening are meant to evoke time passing and an increasing sense of hopelessness, but I didn’t feel that, I just felt bored. Still, while I can conceive of cutting maybe 10 or 20 minutes and the film being just as effective, being a full hour shorter — as the theatrical cut is — must’ve lost a lot of great stuff.

It’s incredibly shot by DP Jost Vacano. The sets are tiny, which feels realistic and claustrophobic, but nonetheless they pull off long takes with complex camera moves. Remarkable. Even more striking is the sound design. It has one of the most powerful and convincing surround sound mixes I’ve experienced, really placing you in the boat as it creaks and drips all around you. The music by composer Klaus Doldinger is also often effective. It does sound kinda dated at times — ’80s electronica — but mostly I liked it.

Versions

Das Boot exists in quite a few different cuts, although The Director’s Cut is the only one currently available on Blu-ray in the UK. If you’re interested in all the different versions, it’s quite a minefield — there are two different TV miniseries versions (a three-part BBC one and a six-part German one), in addition to what’s been released as “The Original Uncut Version”, as well as both of the movie edits. There’s a lengthy comparison of The Director’s Cut and the German TV version here, which lists 75 minutes of major differences and a further 8 minutes of just tightening up. Plus, the TV version also has Lt. Werner’s thoughts in voiceover, which are entirely missing from The Director’s Cut. That means this version “has a lack of information and atmosphere”, according to the author of the comparison.

As to the creation of The Director’s Cut, the Blu-ray contains a whole featurette about it called The Perfect Boat. In it, Petersen explains that he thought the TV version was too long, but that there was a good version to be had between it and the theatrical cut. It was first mooted as early as 1990, but it was when DVD began to emerge that things got moving — Columbia (the studio, not the country) was aware of the format’s potential even from its earliest days, and so it was with an eye on that market that they agreed to fund the new cut. Not only was it all re-edited, but as for that soundtrack I was so praiseful of, the audio was basically entirely re-recorded to make it more effective as a modern movie. The only thing they kept was the original dialogue… which had all been dubbed anyway, because the on-set sound was unusable.

In the end, the new cut was such a thorough re-envisioning that it took three times as long as anticipated, and led to a glitzy premiere and theatrical re-release. Petersen thinks the main difference between the theatrical and director’s cuts is the latter is more rich and has more gravitas because we spend more time with the individual characters.

Das Boot: The Director’s Cut was viewed as part of my What Do You Mean You Haven’t Seen…? 2018 project.

It placed 22nd on my list of The 26 Best Films I Saw For the First Time in 2018.

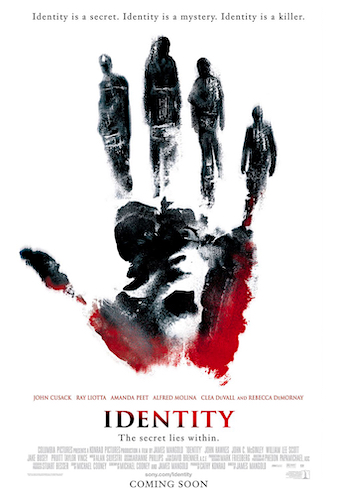

Identity

(2003)

2018 #78

James Mangold | 90 mins | streaming (HD) | 16:9 | USA / English | 15 / R

I bought Identity probably 15 or so years ago in one of those 3-for-£20 or 5-for-£30 sales that used to be all the rage at the height of DVD’s popularity, and no doubt contributed massively both to the format’s success and even regular folk having “DVD collections” (as opposed to just owning a handful of favourite films). As with dozens (ok, I’ll be honest: hundreds) of other titles that I purchased in a more-or-less similar fashion, it’s sat on a shelf gathering dust for all this time, its significance as a piece of art diminishing to the point I all but forgot I owned it.

But I did finally watch it, not spurred by anything other than the whim of thinking, “yeah, I ought to finally watch that,” which just happens for me with random old DVDs now and then. But, like so many other older films that I own on DVD, I found it was available to stream in HD, so I watched it that way instead. The number of DVDs I’ve ended up doing that with, or could if I wanted… all that wasted money… it doesn’t bear thinking about.

Anyway, the film itself. On a dark and stormy night, a series of chance encounters strand ten disparate strangers at an isolated motel, where they realise they’re being murdered one by one. So far, so slasher movie. And, indeed, that’s more or less how it progresses. But there’s a twist or two in the final act that attempts to make it more than that. Without spoiling anything, I felt like it was an interesting concept for a thriller, but at the same time that it didn’t really work. There’s an aspect to the twist that is a cliché so damnable it’s rarely actually used (unlike most other clichés, which pop up all the time), and so the film attempts a last-minute explanation of why it’s better than that, but, I dunno, I feel like a cliché is a cliché.

So maybe Identity is best considered as just a straight B-movie-ish slasher, and just overlook the final act’s attempts at being more interesting as just trying to be different. In fact, more interesting to me was the fact it was mostly shot on an enormous soundstage set, which is kinda cool given the scope of the location.

British Academy Film Awards 2020

British Academy Film Awards 2020