Of the 22 Blindspot/WDYMYHS films I watched in 2018, I still haven’t posted reviews for 18 of them. (Jesus, really?! Ugh.) So, here are three to get that ball rolling.

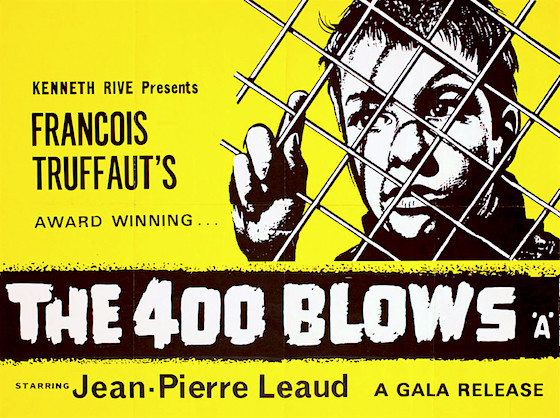

(1959)

François Truffaut | 100 mins | streaming (HD) | 2.35:1 | France / French | PG

One of the first films to bring global attention to La Nouvelle Vague, François Truffaut’s semi-autobiographical drama introduces us to Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a schoolboy in ’50s Paris who plays havoc both at home and at school, which naturally winds up getting him in trouble. The film is both a portrait of misunderstood youth (Antoine isn’t so much bad as bored) and indictment of its treatment (neither his school nor parents make much effort to understand him, eventually throwing him away to a centre for juvenile delinquents).

The film barely contains one blow, never mind 400, which is because the English title isn’t really accurate: it’s a literal translation of the original, which is derived from the French idiom “faire les quatre cents coups“, the equivalent meaning of which would be something like “to raise hell”. Imagine the film was called Raising Hell and it suddenly makes a lot more sense.

Anyway, that’s beside the point. As befits a film at the forefront of a new movement, The 400 Blows feels edgy and fresh, that aspect only somewhat blunted by its 60-year age. I was thinking how it was thematically ahead of its time, but I suppose Rebel Without a Cause was also about disaffected youth and that came out a few years earlier, so I guess it’s more in the how than the what that 400 Blows innovated.

Either way, it’s an engaging depiction of rebellious youth, that remains more accessible than you might expect from a film with its art house reputation.

(2003)

Tim Burton | 125 mins | streaming (HD) | 1.85:1 | USA / English & Cantonese | PG / PG-13

After getting distracted into the mess that was his version of Planet of the Apes, Tim Burton returned to the whimsical just-outside-reality kind of fantasy that had made his name. Based on a novel by Daniel Wallace, it’s about the tall tales of a dying man (played by Albert Finney on his deathbed and Ewan McGregor in his adventurous prime), and his adult son (Billy Crudup) who wants to learn the truth behind those fantastical stories.

Most of Big Fish is fun. It exists at the perfect juncture between Burton’s sense of whimsy and a more realistic approach to storytelling — he’s reined in compared to some of the almost self-parodic works he’d go onto shortly afterwards made since, but it doesn’t seem like he’s constrained, just restrained. With a mix of many funny moments, some clever ones, and occasional somewhat emotional ones, it ticks along being being all very good.

But then the ending comes along, and it hits like a freight train of feeling, clarifying and condensing everything that the whole movie has been about into a powerful gut-punch of emotion. It’s that which elevates the film to full marks, for me.

(1951)

Alfred Hitchcock | 101 mins | Blu-ray | 1.37:1 | USA / English | PG / PG

Alfred Hitchcock’s adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s thriller novel, in which two men get chatting on a train and agree to commit a murder for each other — as you do. In fact, one of the men — tennis star Guy Haines (Farley Granger) — was just making polite conversation and doesn’t want to be involved; but the other — good-for-nothing rich-kid (and, as it turns out, psychopath) Bruno Antony (Robert Walker) — really meant it, and sets about executing the plan.

Strangers on a Train is, I think, most famous for that premise about two strangers agreeing to commit each other’s murder; so it’s almost weird seeing the rest of the movie play out beyond that point — I had no idea where the story was actually going to go with it. It’s a truly great starting point — the kind of “what if” conversation you can imagine really having — and fortunately it isn’t squandered by what follows — the “what if” scenario spun out into “what if you actually followed through?” Naturally, I won’t spoil where it goes, especially as you can rely on Hitch to wring every ounce of suspense and tension out of the premise.

Aside from Hitch’s skill, the standout turn comes from Walker, who makes Bruno a delicious mix of charming and scheming, confident and pathetic, and brings out the homosexual subtext without rubbing it in your face (well, it was the ’50s).

The 400 Blows, Big Fish, and Strangers on a Train were all viewed as part of Blindspot 2018, which you can read more about here.

Jack Palance is an actor wanting out of his studio contract in this stagey film noir.

Jack Palance is an actor wanting out of his studio contract in this stagey film noir. Partially driven by a seeming twist that’s obvious from the outset (which, in fairness, the film reveals only 40 minutes in), the story never quite comes alive. Palance and Corey make parts worth watching, but at other times it’s a bit of a slog, not helped by an awful score that chimes in now and then, loudly. Expansive cinematography (so much headroom — was it shot to be cropped for widescreen? Perhaps it was) combats any feeling of claustrophobia the single location and oppressive moral situation might have leant it.

Partially driven by a seeming twist that’s obvious from the outset (which, in fairness, the film reveals only 40 minutes in), the story never quite comes alive. Palance and Corey make parts worth watching, but at other times it’s a bit of a slog, not helped by an awful score that chimes in now and then, loudly. Expansive cinematography (so much headroom — was it shot to be cropped for widescreen? Perhaps it was) combats any feeling of claustrophobia the single location and oppressive moral situation might have leant it. Box office gross is one of the methods most often used to summarise a film’s success and standing, and yet it’s one of the most useless markers of quality — and quotes like the above, from Terrence Rafferty in his article “Holy Terror” for Criterion’s Blu-ray release of Night of the Hunter (and available online

Box office gross is one of the methods most often used to summarise a film’s success and standing, and yet it’s one of the most useless markers of quality — and quotes like the above, from Terrence Rafferty in his article “Holy Terror” for Criterion’s Blu-ray release of Night of the Hunter (and available online  In another piece in Criterion’s booklet, “Downriver and Heavenward with James Agee” (online

In another piece in Criterion’s booklet, “Downriver and Heavenward with James Agee” (online  And yet, as Rafferty explains, “the most radical aspect of The Night of the Hunter… is its sense of humor. More conventional horror movies overdo the solemnity of evil. The monster in The Night of the Hunter is so bad he’s funny. Laughton and Mitchum treat evil with the indignity it deserves.” I wouldn’t say that humour is one of the film’s defining characteristics, to be honest, but it does undercut its villain. He’s not some unstoppable supernatural creature, but a man who can trip over while chasing you up the stairs, and so on. In some respects it’s this very ordinariness that makes him so scary: however much they creep you out during the film itself, you know there’s no such thing as vampires or werewolves or ghosts. There are Powells in the world, though; an everyday evil that you might not see coming, but can still get you. Brr.

And yet, as Rafferty explains, “the most radical aspect of The Night of the Hunter… is its sense of humor. More conventional horror movies overdo the solemnity of evil. The monster in The Night of the Hunter is so bad he’s funny. Laughton and Mitchum treat evil with the indignity it deserves.” I wouldn’t say that humour is one of the film’s defining characteristics, to be honest, but it does undercut its villain. He’s not some unstoppable supernatural creature, but a man who can trip over while chasing you up the stairs, and so on. In some respects it’s this very ordinariness that makes him so scary: however much they creep you out during the film itself, you know there’s no such thing as vampires or werewolves or ghosts. There are Powells in the world, though; an everyday evil that you might not see coming, but can still get you. Brr. In

In  Often noted merely for being filmed in Los Angeles’ busy train station, there are some spirited defences of Union Station to be

Often noted merely for being filmed in Los Angeles’ busy train station, there are some spirited defences of Union Station to be  Before he was the romantic male lead in musicals like

Before he was the romantic male lead in musicals like  Besides, even if the film seems to forgo the usual gritty noir trappings for a pleasant “English murder mystery”-type tale at first, it actually has its fair share of dark elements and noir-ish features, which only increase as it goes on: secretive gangsters, nightclub singers, revenge shootings… Then there’s the photography which, again, transitions from a fairly ‘regular’ (for want of a better word) style early on, to a world of rain-slicked streets and high-contrast lighting.

Besides, even if the film seems to forgo the usual gritty noir trappings for a pleasant “English murder mystery”-type tale at first, it actually has its fair share of dark elements and noir-ish features, which only increase as it goes on: secretive gangsters, nightclub singers, revenge shootings… Then there’s the photography which, again, transitions from a fairly ‘regular’ (for want of a better word) style early on, to a world of rain-slicked streets and high-contrast lighting. It’s in the latter’s case that the writing gets a chance to shine, too: the chief’s flashback is littered with snappy dialogue that feels kinda like he’s telling you the story himself, not just a matter-of-fact “here’s what happened earlier” objective account. Other flashbacks retain a degree of subjectivity — we only see events the characters could have witnessed, and in some cases the way they witnessed them (like the cleaning lady who only sees customers’ feet, before spying through a keyhole in a shot complete with keyhole matte) — but there’s an idea there, briefly glimpsed in that detective’s flashback, that would’ve made for an even more interesting film.

It’s in the latter’s case that the writing gets a chance to shine, too: the chief’s flashback is littered with snappy dialogue that feels kinda like he’s telling you the story himself, not just a matter-of-fact “here’s what happened earlier” objective account. Other flashbacks retain a degree of subjectivity — we only see events the characters could have witnessed, and in some cases the way they witnessed them (like the cleaning lady who only sees customers’ feet, before spying through a keyhole in a shot complete with keyhole matte) — but there’s an idea there, briefly glimpsed in that detective’s flashback, that would’ve made for an even more interesting film. A bomb is stuck to the underside of a car. As the vehicle pulls away, the camera drifts up into the sky, and proceeds to follow the automobile through the streets of a small Mexican border town, until it crosses the border into the US… and explodes. It’s probably the most famous long take in film history, and probably the thing Touch of Evil is most widely known for; that, and it being one of the most commonly-cited points at which the classic film noir era comes to an end.

A bomb is stuck to the underside of a car. As the vehicle pulls away, the camera drifts up into the sky, and proceeds to follow the automobile through the streets of a small Mexican border town, until it crosses the border into the US… and explodes. It’s probably the most famous long take in film history, and probably the thing Touch of Evil is most widely known for; that, and it being one of the most commonly-cited points at which the classic film noir era comes to an end. It’s like a terrible fever dream, with events and characters that sometimes seem disconnected, but nonetheless interweave through a dense plot. In this sense Welles puts us quite effectively in the shoes of Vargas and his wife — out of our depth, out of our comfort zone, out of control, struggling to keep up and keep afloat. It might be unpleasant if it wasn’t so engrossing.

It’s like a terrible fever dream, with events and characters that sometimes seem disconnected, but nonetheless interweave through a dense plot. In this sense Welles puts us quite effectively in the shoes of Vargas and his wife — out of our depth, out of our comfort zone, out of control, struggling to keep up and keep afloat. It might be unpleasant if it wasn’t so engrossing. Quinlan at all… there is not the least spark of genius in him; if there does seem to be one, I’ve made a mistake.” You can get pretentious about it all you want, and bring to bear political views that the film doesn’t support (after all, within the film Quinlan is punished for his crimes and the “mediocre” (Truffaut’s word) moral hero triumphs), but sometimes a spade is a spade; sometimes a villain is a villain; sometimes your disgusting moral perspective isn’t being covertly supported by a film that seems to condemn it.

Quinlan at all… there is not the least spark of genius in him; if there does seem to be one, I’ve made a mistake.” You can get pretentious about it all you want, and bring to bear political views that the film doesn’t support (after all, within the film Quinlan is punished for his crimes and the “mediocre” (Truffaut’s word) moral hero triumphs), but sometimes a spade is a spade; sometimes a villain is a villain; sometimes your disgusting moral perspective isn’t being covertly supported by a film that seems to condemn it. Notably and obviously absent from that list is Touch of Evil. It was taken away from Welles during the editing process, and though he submitted an infamous 58-page memo of suggestions after seeing a later rough cut, only some were followed in the version ultimately released. Time has brought change, however, and there are now multiple versions of Touch of Evil for the viewer to choose from; but whereas history often resolves one version of a film to be the definitive article, it’s hard to know which that is in this case. Indeed, it’s so contentious that Masters of Cinema went so far as to include five versions on their 2011 Blu-ray (it would’ve been six, but Universal couldn’t/wouldn’t supply the final one in HD.) The version I chose to watch, dubbed the “Reconstructed Version”, tries to recreate Welles’ vision, using footage from the theatrical cut and a preview version discovered in the ’70s to follow his notes. Despite the best intentions of its creators, this can only ever be an attempt at restoring what Welles wanted. Equally, although it was the version originally released, the theatrical cut ignores many of the director’s wishes — so as neither version was finished by Welles, surely the one created by people trying to enact his wishes is preferable to the one assembled by people who only took his ideas on advisement?

Notably and obviously absent from that list is Touch of Evil. It was taken away from Welles during the editing process, and though he submitted an infamous 58-page memo of suggestions after seeing a later rough cut, only some were followed in the version ultimately released. Time has brought change, however, and there are now multiple versions of Touch of Evil for the viewer to choose from; but whereas history often resolves one version of a film to be the definitive article, it’s hard to know which that is in this case. Indeed, it’s so contentious that Masters of Cinema went so far as to include five versions on their 2011 Blu-ray (it would’ve been six, but Universal couldn’t/wouldn’t supply the final one in HD.) The version I chose to watch, dubbed the “Reconstructed Version”, tries to recreate Welles’ vision, using footage from the theatrical cut and a preview version discovered in the ’70s to follow his notes. Despite the best intentions of its creators, this can only ever be an attempt at restoring what Welles wanted. Equally, although it was the version originally released, the theatrical cut ignores many of the director’s wishes — so as neither version was finished by Welles, surely the one created by people trying to enact his wishes is preferable to the one assembled by people who only took his ideas on advisement? To quote from Master of Cinema’s booklet, “the familiar Wellesian framing appears in 1.37:1: indeed, the “world” of the film setting emerges with little or no empty space at the top and bottom of the frame, almost certainly beyond mere coincidence.” There are things to recommend the widescreen experience (“a more tightly-wound, claustrophobic atmosphere”), and undoubtedly the debate will continue… and such is the wonders of the modern film fan that, rather than having to make do with someone else’s decision on what to put out, all the alternatives are at our fingertips.

To quote from Master of Cinema’s booklet, “the familiar Wellesian framing appears in 1.37:1: indeed, the “world” of the film setting emerges with little or no empty space at the top and bottom of the frame, almost certainly beyond mere coincidence.” There are things to recommend the widescreen experience (“a more tightly-wound, claustrophobic atmosphere”), and undoubtedly the debate will continue… and such is the wonders of the modern film fan that, rather than having to make do with someone else’s decision on what to put out, all the alternatives are at our fingertips. Remembered largely thanks to the involvement of Orson Welles (he has a supporting role, produced it, co-wrote it, and reportedly directed a fair bit too, though he denied that), Journey into Fear is an adequate if unsuspenseful World War 2 espionage thriller, redeemed by a strikingly-shot climax. The latter — a rain-drenched shoot-out between opponents edging their way around the outside of a hotel’s upper storey — was surely conducted by Welles; so too several striking compositions earlier in the movie.

Remembered largely thanks to the involvement of Orson Welles (he has a supporting role, produced it, co-wrote it, and reportedly directed a fair bit too, though he denied that), Journey into Fear is an adequate if unsuspenseful World War 2 espionage thriller, redeemed by a strikingly-shot climax. The latter — a rain-drenched shoot-out between opponents edging their way around the outside of a hotel’s upper storey — was surely conducted by Welles; so too several striking compositions earlier in the movie. all added by Welles after the studio had their way, which seems to be the one US viewers know. The version without those seems to be the only one shown on UK TV, however.)

all added by Welles after the studio had their way, which seems to be the one US viewers know. The version without those seems to be the only one shown on UK TV, however.)