I’ve fallen terribly behind with these 100-Week Roundups — I should be on to films from 2019 by now (because 100 weeks is c.23 months), but I still have 17 reviews from 2018 to go. I considered trying to cram more into each roundup, but that just takes longer to compile, so my aim is to post a more-than-average number of roundups in the next fortnight with the goal of at least completing 2018 before 2020 ends. We’ll see how that goes.

Hitchcock/Truffaut (2015)

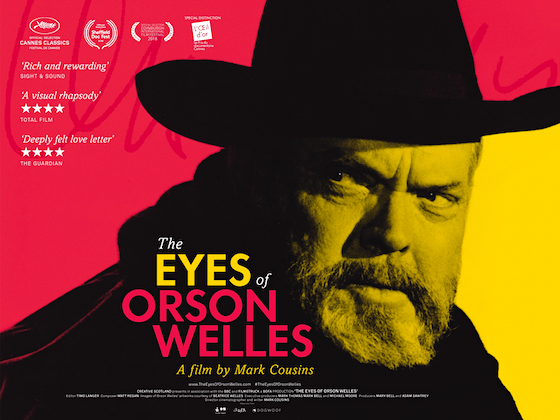

The Other Side of the Wind

(2018)

2018 #226

Orson Welles | 122 mins | digital (UHD) | 1.37:1 + 1.85:1 | France, Iran & USA / English | 15 / R

One of my draft intros for The Other Side of the Wind was to talk about how it feels like “a 2018 film” because it’s different; innovative; unique — modern. But then to note that, of course, it was all shot in the 1970s, but never completed for financial and legal reasons. That’s only partially true, though, because while it does feel modern in some ways, it still looks and feels very ’70s; and while it’s no doubt experimental and avant-garde, it’s in a very ’70s way. And the look of the film stock is very ’70s. It’s a strange, undoubtedly compromised movie — but so are many of the films Orson Welles managed to complete while he was alive, thanks to studio interference, so it’s hardly a sore thumb in that regard.

The film tells the story of the final days of Jake Hannaford (John Huston), a film director working on his comeback movie (you’ve gotta think there’s some autobiography in here, then, right?) It’s a portrait of the man’s final hours, supposedly assembled from dozens of sources that were shooting him at the time — Welles prefiguring the ‘found footage’ genre by a decade or two. But this isn’t a horror movie… well, not in the traditional sense: in my notes I described it as “a frantically-cut display of pompous self-declared intellectuals pontificating about something and nothing in a battle of pretentiousness. That perhaps explains why, at a time when Netflix movies routinely ‘break out’, the flash of interest the film’s release provoked has not resulted in any kind of sustained wide admiration.

Whatever your thoughts on the final film (and it’s clearly one for cineastes and completists rather than general audiences), it seems remarkable that it took so long for anyone to be willing to fund the completion of a film by The Great Orson Welles. But that’s actually a story unto itself, told in the accompanying documentary A Final Cut for Orson: 40 Years in the Making (which is hidden in the film’s “Trailers & More” section, but is definitely worth seeking out if you’re interested). Among the revelations there are that Welles shot almost 100 hours of footage, spread across 1,083 film elements, all of which had to be fully inventoried. Matching it up was a problem that would have been insurmountable even ten years ago; it’s only possible now thanks to digital techniques and algorithms — and, of course, a big chunk of change from Netflix. Welles had only cut together about 45 minutes, with the rest completed based on the style of those parts, his notes and letters, and recordings of some of his direction that was retained on the sound reels.

Was the effort worth it? It’s certainly a fascinating project to see brought to some kind of fruition. In the end, I’m not sure what it all signified. The story is pretty straightforward, but it’s jumbled in amongst a lot of hyperactive editing, as well as a bizarre film-within-a-film. There are things here which still feel ahead of their time even now, and things that were certainly ahead of their time when shot in the early ’70s (even if other people have done them since), which is always exciting. Combine that with Welles’s status and this is unquestionably a fascinating, must-see movie for cinephiles.

Batman & Mr. Freeze: SubZero

(1998)

2018 #227

Boyd Kirkland | 67 mins | Blu-ray | 1.33:1 | USA / English | PG

It’s now so ingrained in Bat-canon that it’s easy to forget, but Batman: The Animated Series actually invented Mr Freeze’s backstory about his dead wife, etc. It was so successful that the episode (Heart of Ice) won an Emmy, the character was brought back to life in the comics (complete with this new backstory), and just a few years later it was used in Batman & Robin (which, considering how much that film was happy to ignore about other characters, e.g. Bane, just goes to show… something).

So, with The Animated Series responsible for such a major revival of the character, it kinda makes sense they’d choose him to star in their second animated feature — although another version of events is he was chosen to tie-in with Batman & Robin, but then SubZero was pushed back after the live-action film was a critical flop. That makes sense, because while Heart of Ice is fantastic and influential, none of Freeze’s other Animated Series appearances have a great deal to offer. TV episode Deep Freeze is sci-fi B-movie gubbins featuring Freeze as a cog in the plot rather than its driving force; and, after all the effort to humanise him, in Cold Comfort he’s just a villain doing villainous things with incredibly thin motivation.

SubZero is, at least, a step above those. It doesn’t withstand comparison to its predecessor movie, the genuine classic Mask of the Phantasm — that had entertainment value for kids, but was also a thoughtful, mature story about what drives Bruce Wayne to be Batman. SubZero, on the other hand, is just an action-adventure ride. It’s not bad for what it is (there’s a pretty great car chase halfway through, and the explosive climax aboard an abandoned oil derrick going up in flames is rather good), but no more than that. At least it finally provides a neat end to Freeze’s story… even if it is kinda hurried in a last-minute news report.

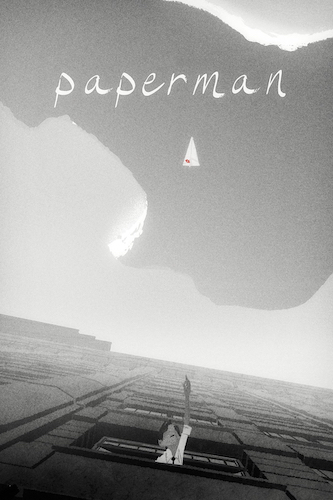

Paper Moon

(1973)

2018 #235

Peter Bogdanovich | 98 mins | TV (HD) | 1.85:1 | USA / English | PG / PG

I do try to avoid this situation arising in a ‘review’, but I watched Paper Moon over two years ago and didn’t make any significant notes on it, so I’m afraid I can’t say much of my own opinion. What I can tell you is that I happened to spot it in the TV schedule and decided to watch it primarily to tick it off the IMDb Top 250, thinking it was a bit of an also-ran on that list (based on iCheckMovies, it’s not very widely regarded outside of IMDb; indeed, it’s not even on the Top 250 anymore). But that was serendipitous, because I wound up really enjoying it.

Sticking with IMDb, here are some interesting points of trivia:

“At 1 hour, 6 minutes, 58 seconds, Tatum O’Neal’s performance is the longest to ever win an Academy Award in a supporting acting category.” I guess category fraud isn’t a recent phenomena: O’Neal’s a lead — the lead, even — but I bet that supporting award was an easier win, especially as she was a child. Which also ties to this item: “some Hollywood insiders suspected that O’Neal’s performance was ‘manufactured’ by director Peter Bogdanovich. It was revealed that the director had gone to great lengths, sometimes requiring as many as 50 takes, to capture the ‘effortless’ natural quality for which Tatum was critically praised.” But I’ll add a big “hmm” to that point, because I think it’s very much a point of view thing. Every performance in a movie is “manufactured”, in the sense that multiple takes are done and the director and editor later make selections — is requiring 50 takes for a child actor to nail it any different than Kubrick or Fincher putting adult actors through 100 or more takes until they get what they want?

On a more positive note, “Orson Welles, a close friend of Bogdanovich, did some uncredited consulting on the cinematography. It was Welles who suggested shooting black and white photography through a red filter, adding higher contrast to the images.” Good idea, Orson, because the film does look rather gorgeous.

Hitchcock/Truffaut

(2015)

2018 #236

Kent Jones | 77 mins | TV | 16:9 | France & USA / English, French & Japanese | 12 / PG-13

“In 1962, film directors Alfred Hitchcock and François Truffaut locked themselves away in Hollywood for a week to excavate the secrets behind the mise-en-scène in cinema. Based on the original recordings of this meeting — used to produce the mythical book Hitchcock/Truffaut — this film illustrates the greatest cinema lesson of all time… Hitchcock’s incredibly modern art is elucidated and explained by today’s leading filmmakers, who discuss how Truffaut’s book influenced their work.” — adapted from IMDb

This film version of Hitchcock/Truffaut is about so much at once. On balance, it’s mostly about analysing Hitchcock’s films; but it’s also about the interview itself; and the importance and impact of the book, both on the general critical perception of Hitchcock and how it influenced specific directors; but it’s also about how Hitchcock’s actual films have influenced those directors; and there’s also insights into directing from those directors; and also some bits on Truffaut’s films, and the differences between him and Hitchcock as filmmakers. Whew!

It’s a funny film, really: it acknowledges the book’s influence, but doesn’t really dig into it; it analyses some of Hitch’s obsessions and films (most especially Vertigo and Psycho), but not comprehensively. Some have said it feels like a companion piece to the book; I’ve not read the book, but I can believe that — if the book were a movie, this would be a special feature on the DVD. Less kindly, you could call it a feature-length advert — certainly, I really want to get the book now. (I got it as a Christmas present not long after. I’ve not read it yet.)

That said, here’s an iInteresting counterpoint from a Letterboxd review: “One of the things (just one) that makes the book so essential is that it’s a discussion of the craft of filmmaking from two (very different) filmmakers. In adding commentary from a wide variety of other directors, Jones highlights that element of the book while widening and updating its focus: it isn’t just a conversation between Hitchcock and Truffaut, but between those two men and David Fincher, and James Gray and Kyoshi Kurosawa and Arnaud Desplechin, etc. Rather than a mere supplement to the book, a video essay adding moving pictures to the book’s conversations, Jones’s film builds something new and on-going upon it.”

I didn’t think Hitchcock/Truffaut (the film) was all it could be; and yet, thanks to the topics discussed and people interviewed, it’s still a must-see for any fan of Hitchcock, or just movies in general.