Doctor Who:

The Daleks

and

Dr. Who and

the Daleks

Doctor Who: The Daleks

1963-4 | Christopher Barry & Richard Martin | 172 mins | DVD | 4:3 | UK / English | U

Dr. Who and the Daleks

1965 | Gordon Flemyng | 83 mins | Blu-ray | 2.35:1 | UK / English | U

In a fortnight’s time, on the 23rd of November 2013, Doctor Who will celebrate its golden anniversary — 50 years to the day since the premiere broadcast of its first episode, An Unearthly Child. Those 25 minutes of 1960s TV drama still stand up to viewing today. OK, you couldn’t show them on primetime BBC One anymore; but the writing, acting, even the direction, and certainly the sheer volume of ideas squeezed into such a short space of time, are all extraordinary. It is, genuinely, one of the best episodes of television ever produced.

But that’s not why Doctor Who is still here half a century later. It may be the strength of that opening episode, the ideas and concepts it introduced, that has actually sustained the programme through 26 original series, a 16-year break, and 8 years (and counting) of revived mainstream importance;  but that’s not what secured the chance to prove the series’ longevity. That would come a few weeks after the premiere, in the weeks before and after Christmas 1963, when producer Verity Lambert went against her boss’ specific orders and allowed “bug-eyed monsters” into the programme — in the shape of the Daleks.

but that’s not what secured the chance to prove the series’ longevity. That would come a few weeks after the premiere, in the weeks before and after Christmas 1963, when producer Verity Lambert went against her boss’ specific orders and allowed “bug-eyed monsters” into the programme — in the shape of the Daleks.

Something about those pepperpot-shaped apparently-robotic villains clicked with the British public, and Dalekmania was born. Toys and merchandise flowed forth. The series soon began to include serials featuring the Daleks on a regular basis. And, naturally, someone snapped up the movie rights.

Rather than an original storyline, the ensuing film was an adaptation of the TV series’ first Dalek serial. These days you probably wouldn’t bother with such a thing, thanks to the abundance of DVD/Blu-ray/download releases and repeats by both the original broadcaster and channels like Watch; but back then, when TV was rarely repeated and there certainly wasn’t any way to own it, retelling the Daleks’ fabled origins on the big screen probably made sense. Nonetheless, there was an awareness that the filmmakers were asking people to pay for something they could get — or, indeed, had had — for free on the telly. Hence why the film is in super-wide widescreen and glorious colour, both elements emphasised in the advertising. The film is big and bold, whereas the TV series, by comparison, is perhaps a little small, in black & white on that tiny screen in the corner of your living room…

But, really, that was never the point. Doctor Who has always thrived on its stories rather than its spectacle (even today, when there’s notably more spectacle, it’s those episodes that offer original ideas or an emotional impact that endure in fans’ (and regular viewers’) memories). The plot of The Daleks is, by and large, a good’un, and certainly relevant to its ’60s origins —  its inspiration comes both from the Nazis, not yet 20 years passed, and the threat of nuclear annihilation, at a time when the Cold War was at its peak. The film adaptation is so unremittingly faithful (little details have changed, but not the main sweep) that these themes remain, all be it subsumed by the COLOUR and ADVENTURE of the big-screen rendition.

its inspiration comes both from the Nazis, not yet 20 years passed, and the threat of nuclear annihilation, at a time when the Cold War was at its peak. The film adaptation is so unremittingly faithful (little details have changed, but not the main sweep) that these themes remain, all be it subsumed by the COLOUR and ADVENTURE of the big-screen rendition.

The Daleks were, are, and probably always will be, a pretty blatant Nazi analogy. There’s not anything wrong with that, though its debatable how much there is to learn from it. Where it perhaps becomes interesting is the actions of the other characters. Here we’re on the Daleks’ homeworld, Skaro, which is also populated by a race of humanoids, the Thals. They are pacifists and, when they learn the Daleks want to kill them all, decide it would be best to just leave rather than fight back. The Doctor’s companion Ian has other ideas, goading them into standing up for themselves. These days the idea that our heroes would take a pacifist race and turn them into warmongers strikes a bum note; but this is a serial made by a generation who remember the war, perhaps even some who fought in it, and naturally that colours your perception of both warfare and what’s worth fighting for. The Daleks aren’t just some distasteful-to-us foreign regime that maybe we should leave be unless they threaten us directly — they’re Nazis; they’re coming to get us; they must be stopped.

On the other hand, this is contrasted with Skaro itself — an irradiated wasteland, the only plant and animal life petrified, with the Thals and our time-travelling heroes requiring medication to survive. This is a Bad Thing… but this is where war has led, isn’t it? This is why the Thals are pacifists — because they don’t want this to happen again. And then they go and have a fight. Perhaps we shouldn’t be digging so deeply into the themes after all. It’s not that a “children’s series” like Doctor Who is incapable of sustaining their weight, it’s that writer and Dalek creator Terry Nation is really more of an adventure storyteller. That said, he did go on to create terrorists-are-the-good-guys saga Blake’s 7 and how-does-society-survive-post-apocalypse thriller Survivors, so maybe I’m doing him a disservice.

If the film’s rendering of the story and consequent themes is near-identical to its TV counterpart, plenty of other elements aren’t. The most obvious, in terms of adaptation, is that its 90 minutes shorter — roughly half the length. That’s not even the whole story, though: the film is newbie friendly, meaning it spends the first seven minutes introducing the Doctor and his friends. When we take out credits too, it spends 75 minutes on its actual adaption — or a little over 10 minutes for each of the original 25-minute episodes. And yet, I don’t think anything significant is cut. Even the three-episode trek across the planet that makes up so much of the serial’s back half is adapted in full, the only change being one character lives instead of dies (a change as weak as it sounds, in my view).

If the film’s rendering of the story and consequent themes is near-identical to its TV counterpart, plenty of other elements aren’t. The most obvious, in terms of adaptation, is that its 90 minutes shorter — roughly half the length. That’s not even the whole story, though: the film is newbie friendly, meaning it spends the first seven minutes introducing the Doctor and his friends. When we take out credits too, it spends 75 minutes on its actual adaption — or a little over 10 minutes for each of the original 25-minute episodes. And yet, I don’t think anything significant is cut. Even the three-episode trek across the planet that makes up so much of the serial’s back half is adapted in full, the only change being one character lives instead of dies (a change as weak as it sounds, in my view).

The funny thing is, even at such a short length it can feel pretty long. It’s that trek again, as Ian, Barbara and some of the Thals make their way to the back of the Dalek city to mount the climactic assault. It feels like padding to delay the climax, and some say it is: reportedly Nation struggled to fill the seven-episode slot he was given, hence the meandering. When it came to the film, Nation insisted Doctor Who’s script editor David Whittaker was hired to write the screenplay (apparently the trade-off was that producer Milton Subotsky got a credit for it too), which perhaps explains the faithfulness. It’s a shame in a way that Whittaker just produced an abridgement, because a restructured and re-written version for the massively-shorter running time might have paced it up a bit.

The most obvious change — the one that gets the fans’ goat, and why so many dislike the film to this day — comes in those opening seven minutes. On TV, the Doctor (as he is known) is a mysterious alien time traveller, his mid-teen granddaughter Susan is also a bit odd, and Ian and Barbara are a pair of caring teachers who he kidnaps to maintain his own safety. In the film, the title character is Dr. Who — that’s the human Mr. Who with a doctorate — who has a pair of granddaughters, pre-teen Susan and twenty-ish Barbara, while Ian is the latter’s clumsy fancyman. They visit the time machine that Dr. Who has knocked up in his backyard, where clumsy old Ian sends them hurtling off to an alien world. In many respects this is once again the difference between TV and film: the former is an intriguing setup that takes time to explain and will play out over a long time (decades, as it’s turned out — the Doctor is still a mysterious figure, even if we know a helluva lot more about him now than we did at the start of The Daleks), while the latter gives us a quick sketch of some people for 80 minutes of entertainment. Plus, making Ian a bumbler adds some quick comedy, ‘essential’ for a kids’ film.

The most obvious change — the one that gets the fans’ goat, and why so many dislike the film to this day — comes in those opening seven minutes. On TV, the Doctor (as he is known) is a mysterious alien time traveller, his mid-teen granddaughter Susan is also a bit odd, and Ian and Barbara are a pair of caring teachers who he kidnaps to maintain his own safety. In the film, the title character is Dr. Who — that’s the human Mr. Who with a doctorate — who has a pair of granddaughters, pre-teen Susan and twenty-ish Barbara, while Ian is the latter’s clumsy fancyman. They visit the time machine that Dr. Who has knocked up in his backyard, where clumsy old Ian sends them hurtling off to an alien world. In many respects this is once again the difference between TV and film: the former is an intriguing setup that takes time to explain and will play out over a long time (decades, as it’s turned out — the Doctor is still a mysterious figure, even if we know a helluva lot more about him now than we did at the start of The Daleks), while the latter gives us a quick sketch of some people for 80 minutes of entertainment. Plus, making Ian a bumbler adds some quick comedy, ‘essential’ for a kids’ film.

Even more different is Peter Cushing’s portrayal of the Doctor. At the start of the TV series, William Hartnell’s rendition of the titular character is spiky, manipulative, tricksy, and in many respects unlikeable. In the first serial he even considers killing someone in order to aid his escape! Not the Doctor we know today. As time went on Hartnell softened, becoming a loveable grandfather figure. It’s this version that Cushing adopts in the film, with a sort of waddly walk and little glasses, looking and behaving completely differently to his roles in all those Hammer horrors. If proof were needed of Cushing’s talent, just put this side by side with one of those films. But this was at a time when Hartnell was the Doctor — with ten men ‘officially’ having replaced him in the TV series (not to mention Peter Capaldi to come, a recast Hartnell in The Five Doctors, and various others on stage, audio, fan films, and so on), it’s easy to forget that Cushing taking over must have been a bit weird. It certainly put Hartnell’s nose out of joint. And for all Cushing’s niceness and versatility across his career, Hartnell’s Doctor is a more varied, nuanced, and interesting character.

(not to mention Peter Capaldi to come, a recast Hartnell in The Five Doctors, and various others on stage, audio, fan films, and so on), it’s easy to forget that Cushing taking over must have been a bit weird. It certainly put Hartnell’s nose out of joint. And for all Cushing’s niceness and versatility across his career, Hartnell’s Doctor is a more varied, nuanced, and interesting character.

You can see why fans don’t like it — it’s not proper Doctor Who. I think that’s not helped by the film’s prominence in the minds of ordinary folk. During the ’90s, when Who was out of favour at the BBC (except with Enterprises/Worldwide, for whom it’s always made a fortune), the main way to see it was with repeats of the films on TV. Even before that, I’m sure the films have been screened much more regularly than the serials that inspired them. Plus the general public don’t understand that Cushing isn’t a real Doctor (even now, you see people asking why he isn’t in the trailers for the 50th anniversary, and so on), which just rubs it in. But if you let that baggage go (which you really should), Dr. Who and the Daleks is an entertaining version of the TV serial.

And yet… it isn’t as good. The widescreen colour looks good, sure, and the Daleks’ tall ‘ears’ are an improvement (hence why they were adopted for TV in the 2005 revival), but other than that the design is lacking.  The console room in the TARDIS is another iconic piece of design, the six-sided central console and roundel-decorated walls having endured in one form or another throughout the show’s life (even if some of it’s become increasingly obscured in the iterations since the 1996 TV movie). In the film, however, it’s just… a messy room. There are control units and chairs and stuff bunged around, with a mess of wires draped about the place. On TV it looks like a slick futuristic spaceship; on film it looks like a junkyard. Oh dear.

The console room in the TARDIS is another iconic piece of design, the six-sided central console and roundel-decorated walls having endured in one form or another throughout the show’s life (even if some of it’s become increasingly obscured in the iterations since the 1996 TV movie). In the film, however, it’s just… a messy room. There are control units and chairs and stuff bunged around, with a mess of wires draped about the place. On TV it looks like a slick futuristic spaceship; on film it looks like a junkyard. Oh dear.

Then there’s the Dalek city. The film’s version is more grand, with lengthy corridors rather than the faked photo-backdrops used on TV; but that’s besides the point, because that very grandness undermines its impact. The Daleks’ corridors on TV feel truly alien — they’re the same height as the Daleks, which is about a foot smaller than most of our leads, meaning they’re constantly having to duck through doorways. It’s perfectly thought-through design, led by how the place would actually have been built rather than making it convenient for the cast. The film’s city is the opposite, with big doorways and rooms. It’s a minor point perhaps, but it can leave an impression.

Ridley Scott is, by and large, a great film director, and is responsible for at least two of the all-time greatest science-fiction movies; but I doubt even his 26-year-old self, then a BBC staff designer originally assigned to work on Doctor Who’s second serial, could have come up with a more iconic look for the Daleks than Raymond P. Cusick. With the exception of the ‘ears’ and the colour scheme, his design is rendered faithfully from TV to film, because it’s so good. Why does it work? I have no idea. Perhaps because it’s genuinely alien — they’re not in any way the same shape or size as a human. Of course, it sort of is: the design is based around being able to fit a man sitting down, in order to control it — but it doesn’t look like that.  Then there’s the way they glide, the screechy voice, the sink-plunger instead of some kind of hand or claw… It’s a triumph, and it works just as well in gaudy colours on film as it does in simple black and white.

Then there’s the way they glide, the screechy voice, the sink-plunger instead of some kind of hand or claw… It’s a triumph, and it works just as well in gaudy colours on film as it does in simple black and white.

Thanks to being just on contract, Cusick’s contribution to the Daleks and Doctor Who can be overlooked. Even after the creatures became a phenomenal success, the most he managed to get was a £100 bonus and a gold Blue Peter badge; though as the latter is practically a knighthood, it could be worse. Nation, meanwhile, reaped the rewards (though no gold badge), to the extent that today his estate control whether the Daleks can appear in Doctor Who or not. Nation gets a credit every time they appear; Cusick doesn’t. Obviously Nation is owed much of this, but Cusick is too: without that design, the Daleks would have been nothing. Thankfully, the making of Doctor Who is probably the most thoroughly researched and documented TV production of all time, and even if he doesn’t get an onscreen credit on new episodes or any financial rewards for his family, Cusick’s name is well-known in fan circles — the outpouring of appreciation when he passed away last February was equal to that received by many of the programme’s leading actors (always a more obvious object of adulation).

I think the Dalek films aren’t given the credit they’re due by many Doctor Who fans. There’s a reason for that, but those reasons are past. The original stories have been available on VHS and then DVD for decades now, meaning the films aren’t the only way to experience these adventures any more. Plus, as the relaunched show has established Doctor Who as a contemporary popular TV series, so the general populace sees it as a franchise that has had three leading men; or, for the better-informed masses, eleven.  Whenever the series brings up past Doctors (and that’s surprisingly often, considering the “come on in, it’s brand new!” tone in 2005), Cushing isn’t among them. While he may once have been a prominent face associated with the show to non-fans, the ‘war’ has been ‘won’ — he’s become a footnote.

Whenever the series brings up past Doctors (and that’s surprisingly often, considering the “come on in, it’s brand new!” tone in 2005), Cushing isn’t among them. While he may once have been a prominent face associated with the show to non-fans, the ‘war’ has been ‘won’ — he’s become a footnote.

Maybe it will take a while for fans to stop being so stuck in their ways, but I hope they do and can embrace the Dalek movies as fun alternatives — they don’t replace the originals, but should stand proudly alongside them as symbols of Doctor Who’s success.

Next time… the Daleks invade Earth twice, as I compare the second Dalek serial to its big screen remake.

There is, I think, a degree of consensus amongst Bond fans (both serious and casual) about a great number of things. Everyone has their personal favourites and dislikes that go against the norm, of course, but there are few things that are genuinely divisive on a large scale. It’s largely accepted that Goldfinger is the distillation of The Bond Formula, for instance; or that any new Bond is judged against the yardstick of Connery; that On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is one of the better films, but long-maligned for its re-cast/miscast lead; that Moore was too old by the end; that GoldenEye was a great re-invention of the franchise; that Casino Royale was the same for a decade later; that Moonraker and Die Another Day and Quantum of Solace are rubbish; and so on. But nonetheless, a couple of things do generate a split of opinion — how good (or not) were Timothy Dalton and his films, for example. This is where I’d place Thunderball.

There is, I think, a degree of consensus amongst Bond fans (both serious and casual) about a great number of things. Everyone has their personal favourites and dislikes that go against the norm, of course, but there are few things that are genuinely divisive on a large scale. It’s largely accepted that Goldfinger is the distillation of The Bond Formula, for instance; or that any new Bond is judged against the yardstick of Connery; that On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is one of the better films, but long-maligned for its re-cast/miscast lead; that Moore was too old by the end; that GoldenEye was a great re-invention of the franchise; that Casino Royale was the same for a decade later; that Moonraker and Die Another Day and Quantum of Solace are rubbish; and so on. But nonetheless, a couple of things do generate a split of opinion — how good (or not) were Timothy Dalton and his films, for example. This is where I’d place Thunderball. there’s an awful lot of grand, expensive-looking underwater stunt work; and it’s relatively long too, the first Bond to pass two hours (and, even in the nicest possible way, it feels it). Accompanying it was an array of merchandising that, at least as I understand it, wouldn’t be seen again for years (these days it’s par for the course, kicked off by Star Wars, but could Lucas’ insistence on retaining and exploiting those rights have been inspired by earlier stuff such as this? I’ve no idea; some Star Wars fan might). The legacy of this is that some people absolutely adore Thunderball, especially if they’re of the generation who saw it on release.

there’s an awful lot of grand, expensive-looking underwater stunt work; and it’s relatively long too, the first Bond to pass two hours (and, even in the nicest possible way, it feels it). Accompanying it was an array of merchandising that, at least as I understand it, wouldn’t be seen again for years (these days it’s par for the course, kicked off by Star Wars, but could Lucas’ insistence on retaining and exploiting those rights have been inspired by earlier stuff such as this? I’ve no idea; some Star Wars fan might). The legacy of this is that some people absolutely adore Thunderball, especially if they’re of the generation who saw it on release. but if you just accept a few of those, allow them to wash over you as it were, then it’s quite good fun. For all its flaws, it’s also packed with brilliant moments: the scene at the Kiss Kiss Club is arguably the best-directed bit in the series to date, and remains one of my favourite moments from any Bond; then there’s the jet pack, indeed the whole opening titles; almost any scene between Bond and one of the numerous females; “I think he got the point”; Domino’s (first) swimming costume… Um, where was I?

but if you just accept a few of those, allow them to wash over you as it were, then it’s quite good fun. For all its flaws, it’s also packed with brilliant moments: the scene at the Kiss Kiss Club is arguably the best-directed bit in the series to date, and remains one of my favourite moments from any Bond; then there’s the jet pack, indeed the whole opening titles; almost any scene between Bond and one of the numerous females; “I think he got the point”; Domino’s (first) swimming costume… Um, where was I?

It’s long been held as a truism that, though it’s the third film, Goldfinger really defined ‘the Bond formula’; and I’ve long argued against that, pointing to the elements that were ready-to-go in

It’s long been held as a truism that, though it’s the third film, Goldfinger really defined ‘the Bond formula’; and I’ve long argued against that, pointing to the elements that were ready-to-go in  However, I did also note that “those parts are mostly so excellent that its still a greatly entertaining film, and, I’m sure, not undeserving of the adulation lavished upon it by so many”, and that’s certainly true. You only have to list bits to bring back fond memories: the pre-titles (filled with multiple memorable moments, even if it’s completely unrelated to the rest of the story); the title song; the title sequence (by Robert Brownjohn, not Maurice Binder); the gold-painted girl; the gold game; Oddjob and the statue; the Q scene (despite Goldfinger’s Q-branch-tour being the archetype, it’s not repeated in a similar manner for decades); the gadget-laden car; the stunning Swiss locations; “no Mr Bond, I expect you to die”; Pussy Galore; the epic raid on Fort Knox; Oddjob and the electricity; the clock stopping at 007; Goldfinger being sucked out of the plane; hiding from rescue in the life raft… That’s quite a haul. Even the less feasible bits, like the cardboard-cut-out gangsters, have a certain charm.

However, I did also note that “those parts are mostly so excellent that its still a greatly entertaining film, and, I’m sure, not undeserving of the adulation lavished upon it by so many”, and that’s certainly true. You only have to list bits to bring back fond memories: the pre-titles (filled with multiple memorable moments, even if it’s completely unrelated to the rest of the story); the title song; the title sequence (by Robert Brownjohn, not Maurice Binder); the gold-painted girl; the gold game; Oddjob and the statue; the Q scene (despite Goldfinger’s Q-branch-tour being the archetype, it’s not repeated in a similar manner for decades); the gadget-laden car; the stunning Swiss locations; “no Mr Bond, I expect you to die”; Pussy Galore; the epic raid on Fort Knox; Oddjob and the electricity; the clock stopping at 007; Goldfinger being sucked out of the plane; hiding from rescue in the life raft… That’s quite a haul. Even the less feasible bits, like the cardboard-cut-out gangsters, have a certain charm. If you think about it too much then the plot is like a machine-gunned windscreen — spattered with holes. But they’re mostly minor niggles rather than glaring errors, and it’s more than covered by the fun you’re having. There are several films that would contend the top spot on my list of Favourite Bond Films and Goldfinger probably isn’t one of them, but that’s a personal thing and it’s surely destined for at least the top ten.

If you think about it too much then the plot is like a machine-gunned windscreen — spattered with holes. But they’re mostly minor niggles rather than glaring errors, and it’s more than covered by the fun you’re having. There are several films that would contend the top spot on my list of Favourite Bond Films and Goldfinger probably isn’t one of them, but that’s a personal thing and it’s surely destined for at least the top ten.

If

If  She’s drugged so perhaps it’s not entirely uncalled for, especially by the era’s standards, but it still strikes the viewer. Plus he’s not throwing out puns at every opportunity, or quipping with every particularly notable dispatch of a villain, but instead tosses the odd line or even just glance. There’s a direct line between this and the Craig films, neither of which seemly hugely similar to the more comical Moore (or even Brosnan) era.

She’s drugged so perhaps it’s not entirely uncalled for, especially by the era’s standards, but it still strikes the viewer. Plus he’s not throwing out puns at every opportunity, or quipping with every particularly notable dispatch of a villain, but instead tosses the odd line or even just glance. There’s a direct line between this and the Craig films, neither of which seemly hugely similar to the more comical Moore (or even Brosnan) era. directly from Dr. No to Goldfinger to hollowed out volcanoes in

directly from Dr. No to Goldfinger to hollowed out volcanoes in  “Bond. James Bond.”

“Bond. James Bond.” Yet for that received wisdom about Goldfinger, ever so much of the familiar Bond recipe is here from the off: the gun barrel sequence, a dramatic pre-titles (albeit post-titles here), the music-driven silhouetted-girls-filled title sequence (even if they’re clothed here), Bond’s casual attitude towards women, his dry humour, his relationships with M and Moneypenny, his detective skills, his fighting skills, his driving skills, the megalomaniac villain, his extravagant lair, and of course the Bond girls — indeed, for all of the fame of Goldfinger’s gold-covered beauty on the bed, Honey emerging from the ocean is still the most iconic Bond girl of them all. And I imagine there’s more I’ve neglected to include.

Yet for that received wisdom about Goldfinger, ever so much of the familiar Bond recipe is here from the off: the gun barrel sequence, a dramatic pre-titles (albeit post-titles here), the music-driven silhouetted-girls-filled title sequence (even if they’re clothed here), Bond’s casual attitude towards women, his dry humour, his relationships with M and Moneypenny, his detective skills, his fighting skills, his driving skills, the megalomaniac villain, his extravagant lair, and of course the Bond girls — indeed, for all of the fame of Goldfinger’s gold-covered beauty on the bed, Honey emerging from the ocean is still the most iconic Bond girl of them all. And I imagine there’s more I’ve neglected to include. Plus, freed from the need to constantly Do Bond-Like Things, we get some solid detective work from our hero, rather than just turning up and saving the day. To put it another way, there’s a mystery and a story, not just a series of set pieces.

Plus, freed from the need to constantly Do Bond-Like Things, we get some solid detective work from our hero, rather than just turning up and saving the day. To put it another way, there’s a mystery and a story, not just a series of set pieces.

but that’s not what secured the chance to prove the series’ longevity. That would come a few weeks after the premiere, in the weeks before and after Christmas 1963, when producer Verity Lambert went against her boss’ specific orders and allowed “bug-eyed monsters” into the programme — in the shape of the Daleks.

but that’s not what secured the chance to prove the series’ longevity. That would come a few weeks after the premiere, in the weeks before and after Christmas 1963, when producer Verity Lambert went against her boss’ specific orders and allowed “bug-eyed monsters” into the programme — in the shape of the Daleks. its inspiration comes both from the Nazis, not yet 20 years passed, and the threat of nuclear annihilation, at a time when the Cold War was at its peak. The film adaptation is so unremittingly faithful (little details have changed, but not the main sweep) that these themes remain, all be it subsumed by the COLOUR and ADVENTURE of the big-screen rendition.

its inspiration comes both from the Nazis, not yet 20 years passed, and the threat of nuclear annihilation, at a time when the Cold War was at its peak. The film adaptation is so unremittingly faithful (little details have changed, but not the main sweep) that these themes remain, all be it subsumed by the COLOUR and ADVENTURE of the big-screen rendition.

If the film’s rendering of the story and consequent themes is near-identical to its TV counterpart, plenty of other elements aren’t. The most obvious, in terms of adaptation, is that its 90 minutes shorter — roughly half the length. That’s not even the whole story, though: the film is newbie friendly, meaning it spends the first seven minutes introducing the Doctor and his friends. When we take out credits too, it spends 75 minutes on its actual adaption — or a little over 10 minutes for each of the original 25-minute episodes. And yet, I don’t think anything significant is cut. Even the three-episode trek across the planet that makes up so much of the serial’s back half is adapted in full, the only change being one character lives instead of dies (a change as weak as it sounds, in my view).

If the film’s rendering of the story and consequent themes is near-identical to its TV counterpart, plenty of other elements aren’t. The most obvious, in terms of adaptation, is that its 90 minutes shorter — roughly half the length. That’s not even the whole story, though: the film is newbie friendly, meaning it spends the first seven minutes introducing the Doctor and his friends. When we take out credits too, it spends 75 minutes on its actual adaption — or a little over 10 minutes for each of the original 25-minute episodes. And yet, I don’t think anything significant is cut. Even the three-episode trek across the planet that makes up so much of the serial’s back half is adapted in full, the only change being one character lives instead of dies (a change as weak as it sounds, in my view). The most obvious change — the one that gets the fans’ goat, and why so many dislike the film to this day — comes in those opening seven minutes. On TV, the Doctor (as he is known) is a mysterious alien time traveller, his mid-teen granddaughter Susan is also a bit odd, and Ian and Barbara are a pair of caring teachers who he kidnaps to maintain his own safety. In the film, the title character is Dr. Who — that’s the human Mr. Who with a doctorate — who has a pair of granddaughters, pre-teen Susan and twenty-ish Barbara, while Ian is the latter’s clumsy fancyman. They visit the time machine that Dr. Who has knocked up in his backyard, where clumsy old Ian sends them hurtling off to an alien world. In many respects this is once again the difference between TV and film: the former is an intriguing setup that takes time to explain and will play out over a long time (decades, as it’s turned out — the Doctor is still a mysterious figure, even if we know a helluva lot more about him now than we did at the start of The Daleks), while the latter gives us a quick sketch of some people for 80 minutes of entertainment. Plus, making Ian a bumbler adds some quick comedy, ‘essential’ for a kids’ film.

The most obvious change — the one that gets the fans’ goat, and why so many dislike the film to this day — comes in those opening seven minutes. On TV, the Doctor (as he is known) is a mysterious alien time traveller, his mid-teen granddaughter Susan is also a bit odd, and Ian and Barbara are a pair of caring teachers who he kidnaps to maintain his own safety. In the film, the title character is Dr. Who — that’s the human Mr. Who with a doctorate — who has a pair of granddaughters, pre-teen Susan and twenty-ish Barbara, while Ian is the latter’s clumsy fancyman. They visit the time machine that Dr. Who has knocked up in his backyard, where clumsy old Ian sends them hurtling off to an alien world. In many respects this is once again the difference between TV and film: the former is an intriguing setup that takes time to explain and will play out over a long time (decades, as it’s turned out — the Doctor is still a mysterious figure, even if we know a helluva lot more about him now than we did at the start of The Daleks), while the latter gives us a quick sketch of some people for 80 minutes of entertainment. Plus, making Ian a bumbler adds some quick comedy, ‘essential’ for a kids’ film. (not to mention Peter Capaldi to come, a recast Hartnell in

(not to mention Peter Capaldi to come, a recast Hartnell in  The console room in the TARDIS is another iconic piece of design, the six-sided central console and roundel-decorated walls having endured in one form or another throughout the show’s life (even if some of it’s become increasingly obscured in the iterations since

The console room in the TARDIS is another iconic piece of design, the six-sided central console and roundel-decorated walls having endured in one form or another throughout the show’s life (even if some of it’s become increasingly obscured in the iterations since  Then there’s the way they glide, the screechy voice, the sink-plunger instead of some kind of hand or claw… It’s a triumph, and it works just as well in gaudy colours on film as it does in simple black and white.

Then there’s the way they glide, the screechy voice, the sink-plunger instead of some kind of hand or claw… It’s a triumph, and it works just as well in gaudy colours on film as it does in simple black and white. Whenever the series brings up past Doctors (and that’s surprisingly often, considering the “come on in, it’s brand new!” tone in 2005), Cushing isn’t among them. While he may once have been a prominent face associated with the show to non-fans, the ‘war’ has been ‘won’ — he’s become a footnote.

Whenever the series brings up past Doctors (and that’s surprisingly often, considering the “come on in, it’s brand new!” tone in 2005), Cushing isn’t among them. While he may once have been a prominent face associated with the show to non-fans, the ‘war’ has been ‘won’ — he’s become a footnote.

(see

(see  while the men are capable and get on with things. Poppycock. Barbra is clearly in shock and, even more so, traumatised. It’s a great performance by Judith O’Dea in that regard, thoroughly believable as to how someone with such damage to their mental health might behave. Far from being the weakest or most irritating character, I think she’s the most fascinating, especially when you add in her final reaction.

while the men are capable and get on with things. Poppycock. Barbra is clearly in shock and, even more so, traumatised. It’s a great performance by Judith O’Dea in that regard, thoroughly believable as to how someone with such damage to their mental health might behave. Far from being the weakest or most irritating character, I think she’s the most fascinating, especially when you add in her final reaction. and suddenly you’ve got dozens of men with guns setting up posses, and then military officials apparently in Washington D.C., being hounded by the press; and then our heroes attempt to escape and there’s bombs and shooting and fire and explosions! You become unsure of where it might go next, and that’s never a bad thing.

and suddenly you’ve got dozens of men with guns setting up posses, and then military officials apparently in Washington D.C., being hounded by the press; and then our heroes attempt to escape and there’s bombs and shooting and fire and explosions! You become unsure of where it might go next, and that’s never a bad thing. That may not be to the taste of the gore-hounds that the horror genre can attract (particularly zombie movies, with all their flesh-ripping), but it does make it of more merit to a wider film-fan audience.

That may not be to the taste of the gore-hounds that the horror genre can attract (particularly zombie movies, with all their flesh-ripping), but it does make it of more merit to a wider film-fan audience. After nearly five decades, numerous sequels, innumerable remakes, rip-offs, and films just plain influenced by it, you’d expect a low-budget shocker to have gone stale. The most remarkable thing about Night of the Living Dead, then, is just how well it holds up. It still feels fresh, with a story and style that seem as if it could have been made yesterday, only the fashions and film stock letting us in on its ’60s origins.

After nearly five decades, numerous sequels, innumerable remakes, rip-offs, and films just plain influenced by it, you’d expect a low-budget shocker to have gone stale. The most remarkable thing about Night of the Living Dead, then, is just how well it holds up. It still feels fresh, with a story and style that seem as if it could have been made yesterday, only the fashions and film stock letting us in on its ’60s origins. Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson weren’t the first to bring Hergé’s journalist-adventurer to the big screen, oh no… though you have to go quite far back — and much more obscure — to find the previous efforts.

Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson weren’t the first to bring Hergé’s journalist-adventurer to the big screen, oh no… though you have to go quite far back — and much more obscure — to find the previous efforts. (I don’t know if the BFI DVD includes the original French, Turkish and Greek soundtrack, but on TV it was entirely dubbed into English. There’s a French Blu-ray, but it doesn’t look to be English friendly.)

(I don’t know if the BFI DVD includes the original French, Turkish and Greek soundtrack, but on TV it was entirely dubbed into English. There’s a French Blu-ray, but it doesn’t look to be English friendly.)

There are few things as weird (or, at least, weird in quite the same way) as watching an acclaimed and beloved classic film and… just not getting it. Here’s a paragon of moviemaking; a film that is not only exalted but, crucially, has remained in people’s affections against the forces of age; a thing that has truly stood the test of time… and yet… meh.

There are few things as weird (or, at least, weird in quite the same way) as watching an acclaimed and beloved classic film and… just not getting it. Here’s a paragon of moviemaking; a film that is not only exalted but, crucially, has remained in people’s affections against the forces of age; a thing that has truly stood the test of time… and yet… meh. In the end, I felt like I just didn’t get it. Not that I was watching something bad and I couldn’t fathom why so many people loved it, but that I just didn’t understand what it was I was meant to be seeing. Which is perhaps the same thing. I mean, I can see Kubrick was making an anti-war point at least as much as he was trying to make people laugh, but what do turgid sequences of people reading out numbers and flicking switches contribute to either of those aims? Perhaps the joke is meant to be in how long it goes on for? Like

In the end, I felt like I just didn’t get it. Not that I was watching something bad and I couldn’t fathom why so many people loved it, but that I just didn’t understand what it was I was meant to be seeing. Which is perhaps the same thing. I mean, I can see Kubrick was making an anti-war point at least as much as he was trying to make people laugh, but what do turgid sequences of people reading out numbers and flicking switches contribute to either of those aims? Perhaps the joke is meant to be in how long it goes on for? Like  A near-silent slapstick comedy starring Tommy Cooper and Eric Sykes, I’d never heard of The Plank until MovieMail highlighted it in a recent catalogue — I swear they gave it a fairly thorough write-up and called it a “must see” (or words to that effect), but I can’t find it now… Weird. (Incidentally, if you don’t get

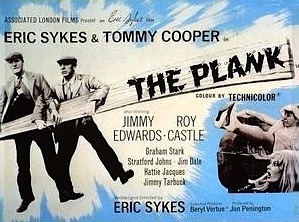

A near-silent slapstick comedy starring Tommy Cooper and Eric Sykes, I’d never heard of The Plank until MovieMail highlighted it in a recent catalogue — I swear they gave it a fairly thorough write-up and called it a “must see” (or words to that effect), but I can’t find it now… Weird. (Incidentally, if you don’t get  There’s actually a surprising amount of dialogue, considering I’ve seen it several times cited as being a silent comedy. The vast majority is inconsequential and there’s no significant humour there, which does render it an almost pointless inclusion — why not go the whole hog and make it dialogue-free? But then, this isn’t

There’s actually a surprising amount of dialogue, considering I’ve seen it several times cited as being a silent comedy. The vast majority is inconsequential and there’s no significant humour there, which does render it an almost pointless inclusion — why not go the whole hog and make it dialogue-free? But then, this isn’t  The ’60s were a pretty exciting time for cinema. In France, the Nouvelle Vague were tearing up the rulebook and pushing forward their own techniques; in Britain, the James Bond series was ditching kitchen sink drama in favour of reinventing the action movie, turning itself into a global phenomenon in the process; and in Italy (and Spain) they were pulling a similar trick on that most American of genres, the Western.

The ’60s were a pretty exciting time for cinema. In France, the Nouvelle Vague were tearing up the rulebook and pushing forward their own techniques; in Britain, the James Bond series was ditching kitchen sink drama in favour of reinventing the action movie, turning itself into a global phenomenon in the process; and in Italy (and Spain) they were pulling a similar trick on that most American of genres, the Western. Much of the film plays as an action movie. There’s a lot of atmospheric ponderousness at the start, but once things kick off they rarely let up. In just over 90 minutes the film rattles through a damsel-in-distress rescue; a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it shoot-out; a 40-on-1 massacre; a raid on a fort; a barroom brawl (one of the stand-outs, that — anyone who thinks handheld ShakeyCam fights are a modern invention should take a look); a tense, silent escape; a brutal punishment (or two); a valley ambush; and a graveyard stand-off. I think that’s all, but I may have missed some. It’s practically a definition of bang for your buck, which I’m sure goes a long way to explaining its popularity.

Much of the film plays as an action movie. There’s a lot of atmospheric ponderousness at the start, but once things kick off they rarely let up. In just over 90 minutes the film rattles through a damsel-in-distress rescue; a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it shoot-out; a 40-on-1 massacre; a raid on a fort; a barroom brawl (one of the stand-outs, that — anyone who thinks handheld ShakeyCam fights are a modern invention should take a look); a tense, silent escape; a brutal punishment (or two); a valley ambush; and a graveyard stand-off. I think that’s all, but I may have missed some. It’s practically a definition of bang for your buck, which I’m sure goes a long way to explaining its popularity. but it’s like watching something on a not-quite-correctly-tuned analogue TV; like you’ve found the channel, but you’re one or two points off the optimum frequency. Or, to put it another way, it’s really snowy. As I said, I’m no expert in BD quality, but this looks like it needs a sympathetic dose of DNR. No one but fools want a

but it’s like watching something on a not-quite-correctly-tuned analogue TV; like you’ve found the channel, but you’re one or two points off the optimum frequency. Or, to put it another way, it’s really snowy. As I said, I’m no expert in BD quality, but this looks like it needs a sympathetic dose of DNR. No one but fools want a