After it had to sit out 2020 entirely (who knows why that happened?!), the Marvel Cinematic Universe is back — but now on TV! *gasp*

Also this month: the continuation of another film-turned-television franchise in Cobra Kai; the examination of film by television in new episodes of Mark Kermode’s Secrets of Cinema; and television that has nothing much to do with film in Staged series 2 and more classic episodes of The Twilight Zone.

WandaVision Episodes 1-4

WandaVision isn’t the first television series set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (in fact, it’s the thirteenth); nor is it the first to feature characters and actors from the movies (that’s been the case in at least two others, off the top of my head); but it is the first to be produced by the same division that makes the movies, so it’s set to be a lot more important (read: not totally ignored) going forward. Indeed, it’s already been reported that the events of this series tie directly into the storylines of the next Spider-Man 3 and Doctor Strange 2, at least.

WandaVision isn’t the first television series set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (in fact, it’s the thirteenth); nor is it the first to feature characters and actors from the movies (that’s been the case in at least two others, off the top of my head); but it is the first to be produced by the same division that makes the movies, so it’s set to be a lot more important (read: not totally ignored) going forward. Indeed, it’s already been reported that the events of this series tie directly into the storylines of the next Spider-Man 3 and Doctor Strange 2, at least.

So it’s a little surprising, then, that this marks such a departure from the regular style and feel of Marvel’s films; much more so than any of their previous TV series did. The setup is that somehow Wanda Maximoff, aka Scarlet Witch, and her robot lover Vision, who died, are living in a world modelled after classic TV sitcoms, and they’re perfectly unaware that there’s anything weird about this. The show emulates these old TV formats down to a tee — it’s not simply that they’ve cropped it to 4:3 and desaturated it to black-and-white, but it’s the camera angles, the acting styles, the set and costume design, the laughter track… The whole vibe of ’60s and ’70s sitcoms is neatly evoked, and the cast are clearly having a ball playing in a different era, with stars Elisabeth Olsen and Paul Bettany particularly up to the task. Plus, the fact this is a nine-episode series, rather than another two-hour action-adventure blockbuster, also allows the show to indulge in old-fashioned standalone-episode storylines, so that each episode feels like a self-contained unit of entertainment, rather than just part of a long movie cut into nine segments

But, of course, something fishy is going on, and when that begins to break through the show cleverly subverts its own format: when a guest starts unexpectedly choking at a dinner party, Wanda urges Vision to use his powers to save him, and the directorial choices suddenly become much more modern, briefly breaking the spell for us as much as the characters, but without doing anything obvious like switching to colour or widescreen. There are increasing flashes of this Twilight Zone-y, Twin Peaks-y, Stepford Wives-y oddness in future episodes, I guess to reassure regular MCU viewers that this is all going somewhere, rather than just being a bit of fluff.

And then we reach episode 4 (spoilers follow). I think we all expected this — i.e. an episode set ‘outside’ that explained (some of) what was going on — to come along at some point. It had to, really. But I thought it would be teased and teased, as it was in the first three episodes, as the show gradually moved through more eras of sitcoms, until eventually we’d start getting to real answers around maybe episode 7 or 8. It’s a very fan pleasing episode — as well as some answers, there’s also a host of roles for minor characters familiar from other MCU outings — but it does slightly concern me for the next five episodes. We know the show is heading back into Wanda’s world, because they’ve promised spoofs of sitcoms from the ’80s, ’90s, and ’00s, but surely it can’t expect to go back to a “sitcom of the week” format and that be sufficient? Now that they’ve opened up the outside, they can’t expect us to just watch Wanda cosplay different eras of sitcom history while learning nothing more about the bigger situation, can they? We’ll have to tune in next week to find out…

Staged Series 2

The David Tennant- and Michael Sheen-starring (or is that Michael Sheen- and David Tennant-starring?) filmed-over-Zoom sitcom about lockdown life was a hit during one or other of the 2020 lockdowns, so here it is again — just in time for the 2021 lockdown, as things turned out. The second series is very much a follow-up — a sequel, if you will — rather than merely “more episodes of the same”. In fact, it’s a meta-sequel: the first series exists as a fictional project in the world of the sequel. This isn’t a continuation of the storyline(s) we watched in the first series; it’s a follow-on from the fact the first series was a success. Got that? The title card sometimes calls the series Staged², and one feels that’s more than just a typographical play on Staged 2.

The David Tennant- and Michael Sheen-starring (or is that Michael Sheen- and David Tennant-starring?) filmed-over-Zoom sitcom about lockdown life was a hit during one or other of the 2020 lockdowns, so here it is again — just in time for the 2021 lockdown, as things turned out. The second series is very much a follow-up — a sequel, if you will — rather than merely “more episodes of the same”. In fact, it’s a meta-sequel: the first series exists as a fictional project in the world of the sequel. This isn’t a continuation of the storyline(s) we watched in the first series; it’s a follow-on from the fact the first series was a success. Got that? The title card sometimes calls the series Staged², and one feels that’s more than just a typographical play on Staged 2.

That said, what we get in practice is more of the same: actors and creatives bickering about a project over video calls. But this time, rather than a play David and Michael are lined up to star in, it’s a Hollywood remake of Staged that won’t star them. Gasp! Cue a parade of famous-face guest stars as potential new cast members. No spoilers here, because the “oh look, it’s him/her” factor is part of the fun, just as it was in the first series; although, frankly, none of this series’ lot (and there are quite a lot) can pull off the same element of surprise as series one’s biggest names. However, this time the celebrity cameos dominate, with David and Michael spending most of the middle episodes meeting people who might replace them. Even bingeing the series over a couple of days, the plot feels spread thin, with very little actually happening to sustain the two hours (yes, across eight episodes it runs only two hours). The subplots that helped fill out series one (Michael’s neighbour; Georgia’s novel; in the extended cut, Lucy’s relationship; and so on) are gone, with nothing significant in their place. There is a sporadic subplot about Georgia, Anna, and Lucy prepping a charity sketch, which makes for some welcome interludes, but that’s only two or three scenes across the whole series.

And yet, ironically, the show tends to be most fun when nothing happens at all, and we’re left with David and Michael chatting to each other. When they’re separated, having different one-on-ones, it’s enjoyable to discover the foibles of another big-name guest star, but the “huh, it’s Person X” element wears off quickly and we want to go back to our leads hanging out. Fortunately, the last two episodes ride in to save the day, first with probably the best pair of guest stars of the series, then with a quite touching finale that simply abandons all the remake schtick to just be about David and Michael’s friendship as lockdown comes to an end. It’s a sweet, touching farewell to a show that I would guess has now run its course, but was a tonic while it lasted.

Mark Kermode’s Secrets of Cinema Series 3

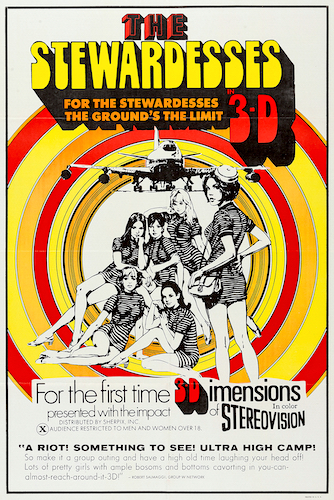

A trio of new editions of the critic’s explanation of cinematic genres, which play like the best Film Studies lectures you could imagine. Each explores and explains its chosen subject in depth, often spinning out into tangential and related branches of film history — see the episode on pop music movies, for example, which is primarily concerned with movies about pop stars or musicals starring pop stars, but takes a moment to explore the phenomenon of pop stars as proper actors, such as David Bowie’s secondary career. It’s like Kermode and his writers (which include the insanely knowledgeable Kim Newman) can’t help themselves: there’s so much interesting stuff to talk about, so many connections and parallels, and they’re going to squeeze as much of it in as possible. Cited examples are copious and wide-ranging — if an episode is about a subject you’re interested in, be prepared to see your watch list grow. The best of this trilogy is the third, on cult movies; a genre, as Kermode explains, that is defined not by filmmakers but by audiences. It’s also a particularly wide-ranging field, but one whose contents engender genuine love — what makes them cult movies, after all, is that someone loves them. Kermode helps us to understand why.

A trio of new editions of the critic’s explanation of cinematic genres, which play like the best Film Studies lectures you could imagine. Each explores and explains its chosen subject in depth, often spinning out into tangential and related branches of film history — see the episode on pop music movies, for example, which is primarily concerned with movies about pop stars or musicals starring pop stars, but takes a moment to explore the phenomenon of pop stars as proper actors, such as David Bowie’s secondary career. It’s like Kermode and his writers (which include the insanely knowledgeable Kim Newman) can’t help themselves: there’s so much interesting stuff to talk about, so many connections and parallels, and they’re going to squeeze as much of it in as possible. Cited examples are copious and wide-ranging — if an episode is about a subject you’re interested in, be prepared to see your watch list grow. The best of this trilogy is the third, on cult movies; a genre, as Kermode explains, that is defined not by filmmakers but by audiences. It’s also a particularly wide-ranging field, but one whose contents engender genuine love — what makes them cult movies, after all, is that someone loves them. Kermode helps us to understand why.

Cobra Kai Season 2

The third season of this Karate Kid TV spinoff/continuation debuted at the start of the month, but I’ve been pacing myself: it’s a really good show and I didn’t want to just burn through it. While I thought season two lacked the moreishness I experienced during season one, I attribute that partly to its quality not coming as a surprise. Also, not tasked with having to set up the whole premise of the show, it can dig a little deeper into what’s already there. That includes more references to the movies. The first is remembered as an ’80s classic; the sequels as an old-fashioned case of diminishing returns — in that situation, many modern revivals choose to ignore the less-favoured follow-ups. Not so Cobra Kai, which this season explicitly references and flashes back to Karate Kid 3 on several occasions. Part of the series’ strength is fleshing out and making real some of the “kids’ movie” logic of the originals, and this season takes on a particularly tough target: the former sensei of Cobra Kai, John Kreese. He’s a bit of an “evil for evil’s sake” villain in the movies, but the series works to add some explanation for that, and even asks if it’s possible that he could be rehabilitated and redeemed, much as former bully Johnny Lawrence has been (or, you might say, is in the process of being).

The third season of this Karate Kid TV spinoff/continuation debuted at the start of the month, but I’ve been pacing myself: it’s a really good show and I didn’t want to just burn through it. While I thought season two lacked the moreishness I experienced during season one, I attribute that partly to its quality not coming as a surprise. Also, not tasked with having to set up the whole premise of the show, it can dig a little deeper into what’s already there. That includes more references to the movies. The first is remembered as an ’80s classic; the sequels as an old-fashioned case of diminishing returns — in that situation, many modern revivals choose to ignore the less-favoured follow-ups. Not so Cobra Kai, which this season explicitly references and flashes back to Karate Kid 3 on several occasions. Part of the series’ strength is fleshing out and making real some of the “kids’ movie” logic of the originals, and this season takes on a particularly tough target: the former sensei of Cobra Kai, John Kreese. He’s a bit of an “evil for evil’s sake” villain in the movies, but the series works to add some explanation for that, and even asks if it’s possible that he could be rehabilitated and redeemed, much as former bully Johnny Lawrence has been (or, you might say, is in the process of being).

The series isn’t just stuck in the past, continuing the rivalries between the high-school-aged students of Cobra Kai and competing Miyagi-Do dojo, both on the karate, er, mat (is that what it’s really called?) and in the romantic realm. I suppose it gives the show a “something for everyone” angle, with both teen melodrama and the reflectiveness of its older characters (one of the season’s best episodes sees Johnny catch up with his old gang from school, one of whom is dying from cancer). All of which builds to a stunning climax: as the kids return to school after the summer break, the opposing factions end up in a karate battle that sprawls through the halls and stairways of the school, fellow students watching and egging them on. It takes up half the episode, including the best hallway fight oner since Daredevil — yes, such lofty comparisons are merited. But, as parents always say, “if you keep doing that, one of you’s going to get hurt”, and so of course it ends in (various kinds of) tragedy. What will happen next?! Oh, season three is already calling to me…

The Twilight Zone

So far on my journey through the original 1959–64 series of The Twilight Zone, I’ve covered ten selections of the best episodes and three of the worst, as chosen by various critics. With 85 episodes still to go, I’m leaving the opinions of others behind (for the time being) to check out some episodes that caught my attention for one reason or another — not because they’re acclaimed as good or derided as bad, but something about the premise grabbed me while I was perusing all those various rankings.

So far on my journey through the original 1959–64 series of The Twilight Zone, I’ve covered ten selections of the best episodes and three of the worst, as chosen by various critics. With 85 episodes still to go, I’m leaving the opinions of others behind (for the time being) to check out some episodes that caught my attention for one reason or another — not because they’re acclaimed as good or derided as bad, but something about the premise grabbed me while I was perusing all those various rankings.

First up, The Bard, in which an enthusiastic wannabe TV writer uses a magic spell to bring Shakespeare back to life, and persuades the Bard to be his ghostwriter. Serling uses his years of experience to make this a satire of the TV industry, but it’s a pretty mild one — probably due to a mix of the era (when I guess the general public wouldn’t have had too much of an idea about the behind-the-scenes of TV) and the fact Serling still had to work in the industry. Also, it was apparently written in a hurry, and it shows: there are some good lines and moments, but various things don’t pay off or go anywhere. Plus, even the story angle is slightly misjudged: surely the gag here is that Shakespeare’s writing appraised by modern TV execs would be a flop; that TV execs would reject the “greatest writer of all time”. Well, at least we get to see Shakespeare punch a pretentious Method actor (played by a young Burt Reynolds), so there’s that.

Based on the same Richard Matheson short story that later inspired Hugh Jackman CGI-fest Real Steel, Steel is set in the future year 1974 (remember, this was made in 1964), when boxing has been outlawed and replaced by robot boxing. The episode centres on one bout, between our heroes’ knackered old B2 robot and a more modern B7, against which the B2 doesn’t stand much chance, despite the hopes of its owner, played by Lee Marvin. I’ve not read the original story, but that’s a broadly similar plot to the film; except here things go in a more Twilight Zone direction: when the B2 breaks down entirely, Marvin decides to enter the ring pretending to be it. The ending tries to spin what occurs as some kind of moral about mankind’s tenacity and optimism, but that feels like a bit of a stretch — the remake reimagining the concept as sports/action entertainment is actually a better use of the concept.

An altogether different vision of 1974 is presented in The Old Man in the Cave. This time, it’s a post-apocalyptic world after “the bomb” was dropped, and what’s left of humanity makes do as it can in the remnants of the old world. In particular, one town has survived by following the guidance of an old man who lives in a nearby cave, who seems to know where to plant food, what tinned goods are safe to eat, what the weather will bring, and so on. When a militia turns up (led by James Coburn) planning to bring order to the region, the townsfolk are faced with the choice of continuing to listen to the old man or side with the militia’s view that he’s actually an oppressor and they’re a lot nicer. It turns into a neat little sci-fi fable — the finale says it’s about the error of faithlessness, but I’m more inclined to say it’s about trust in experts vs selfishness and greed. The townsfolk have followed this expert’s guidance for a decade and it’s kept them alive, but that life hasn’t been easy or fun, so they’re tempted by the fantasy sold by the newcomers: that you can have whatever you want; the expert is keeping you down for no reason. Naturally, it can only pan out one way. It’s a story whose moral seems only more pertinent today.

An altogether different vision of 1974 is presented in The Old Man in the Cave. This time, it’s a post-apocalyptic world after “the bomb” was dropped, and what’s left of humanity makes do as it can in the remnants of the old world. In particular, one town has survived by following the guidance of an old man who lives in a nearby cave, who seems to know where to plant food, what tinned goods are safe to eat, what the weather will bring, and so on. When a militia turns up (led by James Coburn) planning to bring order to the region, the townsfolk are faced with the choice of continuing to listen to the old man or side with the militia’s view that he’s actually an oppressor and they’re a lot nicer. It turns into a neat little sci-fi fable — the finale says it’s about the error of faithlessness, but I’m more inclined to say it’s about trust in experts vs selfishness and greed. The townsfolk have followed this expert’s guidance for a decade and it’s kept them alive, but that life hasn’t been easy or fun, so they’re tempted by the fantasy sold by the newcomers: that you can have whatever you want; the expert is keeping you down for no reason. Naturally, it can only pan out one way. It’s a story whose moral seems only more pertinent today.

The Rip Van Winkle Caper also catapults us into the future, as a gang of gold thieves cryogenically freeze themselves to wake up 100 years after their crime, when their loot won’t be ‘hot’ and, as a bonus, will have benefited from 100 years of inflation. But crime doesn’t pay, even in the Twilight Zone — doubly so in this episode, where the crooks bring about their own destruction even before we reach the episode’s ironic twist. As a sci-fi lesson in where greed gets you (nowhere), it’s not the series’ greatest parable, but it’s not bad.

The same could be said of A Kind of a Stopwatch, which takes on a perennial “what if”: what if you could freeze time? It wasn’t an original idea even when this episode was made in 1964, with Serling once saying he received dozens of pitches a year along those lines. He didn’t think any of them had an original enough take on the concept to be worth adapting, until this one. Frankly, I’m not sure what’s so special about it. That’s not to say it’s bad — it’s a reasonably well handled version, although it falls victim to the series’ regular bad habit of having the main character take much longer than the audience to understand the rules of the situation. But the episode’s real flaw comes at the end, when the punishment doesn’t fit the crime: the main character’s fate is not an ironic twist especially suited to him. It’s that which stops Stopwatch from reaching TZ’s true heights; that leaves it a solid “good” episode when it could possibly have been a great one.

The same could be said of A Kind of a Stopwatch, which takes on a perennial “what if”: what if you could freeze time? It wasn’t an original idea even when this episode was made in 1964, with Serling once saying he received dozens of pitches a year along those lines. He didn’t think any of them had an original enough take on the concept to be worth adapting, until this one. Frankly, I’m not sure what’s so special about it. That’s not to say it’s bad — it’s a reasonably well handled version, although it falls victim to the series’ regular bad habit of having the main character take much longer than the audience to understand the rules of the situation. But the episode’s real flaw comes at the end, when the punishment doesn’t fit the crime: the main character’s fate is not an ironic twist especially suited to him. It’s that which stops Stopwatch from reaching TZ’s true heights; that leaves it a solid “good” episode when it could possibly have been a great one.

Things to Catch Up On

This month, I have mostly been missing It’s a Sin, Russell T Davies’s new drama about a group of friends coming of age amidst the emergence of AIDS in the ’80s. It’s only a couple of episodes in on Channel 4, but the whole five-part series is already available via All 4 (FYI, it’s out in the US on HBO Max in mid-February). I intend to binge the whole thing and review it next month.

This month, I have mostly been missing It’s a Sin, Russell T Davies’s new drama about a group of friends coming of age amidst the emergence of AIDS in the ’80s. It’s only a couple of episodes in on Channel 4, but the whole five-part series is already available via All 4 (FYI, it’s out in the US on HBO Max in mid-February). I intend to binge the whole thing and review it next month.

Next month… more WandaVision, more Twilight Zone, plus whatever else the TV Gods still have left in the pre-pandemic tank and/or have managed to produce during the various lockdowns.

Hunter Killer

Hunter Killer Lovers Rock

Lovers Rock